Book review(s): The Dawn of Eurasia vs Disunited Nations

My comparison review that won Reader's Choice Award for SlaterStarCodex 2021 Book Review Context

I wrote this essay in 2020, with minor updates for COVID. It won Readers’ Choice Award for SlaterStarCodex 2021 the Book Review Context.

The two books:

The Dawn of Eurasia: On the Trail of the New World Order, by Bruno Maçães

Disunited Nations: The Scramble for Power in an Ungoverned World, by Peter Zeihan

The authors liked it:

It’s interesting to see how the world has panned out since.

Zeihan’s vision of a world of rising regional conflict with ascendant regional powers seems to be playing out. Zeihan also seems more right on a depleted Britain than at the time of writing.

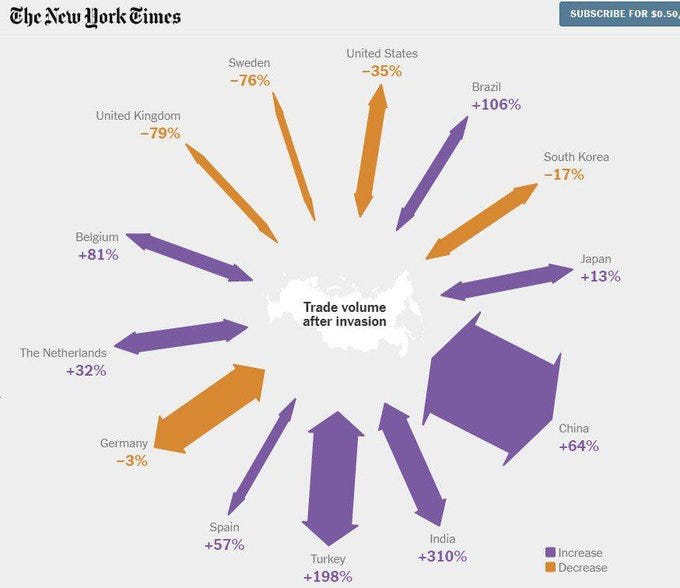

Maçães is right on Eurasian integration, with Russian trade decoupling from Anglo sphere towards China and its other neighbors.

Please enjoy and let me know what you think. Many of my ideas have evolved since, but these books were important to forming my outlook on the world at the time.

The US World Order is coming to an end

The US Navy patrols the world

Zeihan’s geographic determinism

The Dawn of Eurasia

Determinism vs Hope (or Diamond, Zeihan vs Thiel, Deutsch, Maçães)

How much of the future can anyone ever see?

Reversion vs Evolution

The Russian soul

Lighting the path ahead

What does the future look like? We are living through a transition between epochs. Whether marked by COVID-19, the election of Donald Trump or earlier by the global sub-prime crisis, the golden age of post-Cold War prosperity is ending. With the era defined by US political, cultural and economic hegemony, its end is linked to decline in US influence. Will China define this century? Or perhaps Africa, given its forecast population growth? What will become of the US? Of Russia and Europe? Two thinkers seek to define this future.

I first came across Bruno Maçães in 2017 on Marginal Revolution where Tyler Cowen was effusive about Maçães’ new book. I have enjoyed following his conversations and thoughts ever since, but only recently read Dawn of Eurasia. It is the first book of a career politician and diplomat clearly in love with his continent.

Peter Zeihan I came across on Patrick O'Shaughnessy’s excellent podcast. His brash prophesy and contrarian views on geopolitics are hypnotic and endlessly fascinating. Disunited Nations is his latest in a series that documents the rise and rise of US power.

I found comparing them irresistible. Each lingers after reading. It’s that wonderful feeling of discovering a new area of knowledge to mine. Not natural companions, and mesmerising in their own ways, each story has a different texture and plots a different path for the world. Where one sees pessimistic reversion to a historic state of conflict, the other sees hopeful evolution. Where one deterministically condemns nations to their geographic destinies, the other sees each nation’s destiny as unwritten, yet to be informed by its history, literature and peoples.

Both Peter Zeihan and Bruno Maçães see US influence receding. But they agree on little else. Zeihan is deeply pessimistic about a world that awaits a more isolationist US, with a crumbling world order leaving less room for prosperity and reverting to nation-states jostling for food, energy and military security. Maçães sees China’s rise as a harbinger of consolidation on the Eurasian supercontinent, with Europe, Russia and China becoming increasingly interlinked politically and economically. China must grow towards Europe as the US withdraws.

Their most obvious conflict is that Zeihan rejects a “dawn of Eurasia”. Where Maçães foretells super-continental consolidation, Zeihan expects devolvement into tense state competition. But these kinds of differences are less interesting than the differences in their underlying approaches: can there ever be a unifying theory of the future? Can we march forward, to a new place, or is civilisation destined to repeat itself? Can we build our future or are we pulled along the pre-cut grooves of the world we inherited?

1. The US World Order is coming to an end

Zeihan’s Disunited Nations seeks to answer one question: what happens to the prospects of nations when the US withdraws from world affairs? What happens when the post-WWII World Order – along with all the networks of alliances and protected trade routes that comprise it – disintegrates? And the US will withdraw, according to Zeihan. In fact, by global troop deployment, it’s been withdrawing for a while (see chart).

The two things that kept the US interested in maintaining the world order have disappeared: an arch enemy in the Soviet Union and reliance on foreign energy. Continuation of the Order since the collapse of the USSR over the last thirty years has been a result of geopolitical inertia. And energy independence arose with the advent of fracking, when the US became a net crude-oil and products exporter as of 2020.

How exactly does the US maintain the Order? Two ways: the US Navy and free trade.

The Cold War led the US to buy allies into its orbit, through global subsidies via freer trade, protected by naval supremacy. Free trade was never the end, but rather an effective tool to enrich US allies, to buttress against Soviet expansion, says Zeihan. Take Japan, the obliterated former enemy of the US and Axis power: its average Japanese citizen became wealthier than the average US citizen in the mid-eighties. The US effectively subsidised the Japanese citizen to greater wealth than its own. China today is credibly touted as the next global superpower. But it could only become the factory of the world because its shipping routes are protected by US naval supremacy. Post-Cold War, the US no longer has a dog in the fight. It’s increasingly looking for a way out, especially after its two decades long escapades in Iraq and Afghanistan. So what now? It’s… pretty bleak:

“Without the global security the Americans guaranteed, global trade and global energy flows cannot continue. Seven decades’ worth of global industrialization and modernization are not simply at risk, the very pillars of civilization are cracking. In a world without stability, the questions become: Who was most dependent upon the world that was and so will fall? And who was most restrained by the old Order and so will soar?

The world we know is collapsing. Entire countries are watching in horror as what makes them possible—global access, imported energy, foreign markets, American troops—slips through their fingers. For many, there just isn’t enough access or energy or markets or security for them to maintain what they have, much less grow. In a world of want, the questions become: What do countries need to survive in a scrambled world? Who will shoot to get what they need? And who gets shot at?

Not all competitions and scarcities are created equal. Nearly all food is dependent upon global trade, whether in the form of imported inputs or the foodstuffs themselves. For decades, the world’s experiences with famine have been crises of distribution, the inability to match foods with mouths. Global breakdown guts food supply itself. The security concerns of the past two decades were largely limited to terrorism, but the tools necessary to counter terror are radically different from In a world of different scarcities and different tools, the questions become: Where will trade patterns hold and where will they collapse? Which ones are worth fighting over? Which tools will be brought to bear? Are we on the verge of a mess of overlapping and interlocking naval competitions for something as basic as the right to eat?”

Zeihan’s post-US order is one of Hobbesian decline. Whilst US power persists, its position is characterised along similar lines to those used by Maçães: “a splendid isolation, born of power and promising many degrees of freedom”. One of the biggest losers, on the other hand, is China:

“The question is not whether China can be the next global hegemon. It cannot. The real question is whether China can even hold itself together as a country.”

Given the current zeitgeist around China rising, a view to which Maçães subscribes, it is Zeihan’s most contrarian view in a book full of contrarian deviations. Instead of China or Germany or Russia rising, he sees this century as dominated by the US, Japan, Argentina, France and Turkey.

2. The US Navy patrols the world

Following WWII, the US basically had the only navy left. And with the rest of the world in tatters, it had its pick of global naval base positions. Its network today is impossible to replicate. It comes with strategic base positions, decades of naval investment and technological advancement, and operational expertise gained through combat. And Zeihan makes the point with typical panache:

…aside from the Americans, no one floats even a single fully functional supercarrier, much less a supercarrier battle group, much less a global naval force. The next-largest non-American carriers aren’t even really operational. Russia’s Kuznetsov appears to like catching on fire; the UK’s Queen Elizabeth hasn’t yet exited sea trials; India’s Vikramaditya is a floating mass of technical problems; and the engines on France’s Charles de Gaulle aren’t powerful enough to bring it up to aircraft-launching speed except under near-perfect conditions. In fact, the next nine largest fully operational carriers are also all operated by the US Navy.

But Zeihan also makes a deeper point than the happenstance of US naval supremacy. Of course the US Navy was always going to be a naval power. The US is protected by seas and is the rogue child of the greatest naval nation in history, Britain, which is itself an island. And, of course, Britain would have had the greatest navy in history, because it didn’t have Germans and French and Prussians and Russians and Mongols marauding across its borders. This is the heart of Zeihan’s worldview: geographic determinism. Show me a nation’s geography, he says, its weather, its topology, and I will show you its capacity to feed itself, to build infrastructure, to hound its neighbours for energy or be hounded in turn. The US has all it needs where it sits and, by virtue of its surrounding oceans, it’s very hard to invade, and unlikely to disintegrate given the contiguous landscape within. Saudi Arabia, for example, has fewer choices, being a land of sand and oil. China has for eternity battled to maintain its internal cohesion, while being constantly threatened by hostile neighbours on all sides. It could never build a real naval capability by virtue of how disparate its threats are, spreading its focus thin across strategic imperative. In fact, Zeihan can’t stress the meagre nature of China’s current navy and future naval prospects enough:

“With its naval order of battle limited by its small number of long-range ships, China is horrifically dependent upon the ports of others. China’s only reliable ally—stretching the meaning of reliable and ally —is North Korea. As China borders North Korea, North Korean ports—not positioned or designed to support large-scale naval power projection—don’t exactly help the picture. China has therefore pushed a “string of pearls” policy to create a line of friendly ports between the Chinese coast and areas of interest. Malaysia, Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, and Kenya, for example, serve as Chinese pearls on the all-important energy-shipping route from the Persian Gulf. A big piece of China’s One Belt, One Road (OBOR) diplomatic effort is to rope such countries into China’s sphere of influence. The path the Chinese have followed is rather sophomoric: Beijing insists that the funds it has provided to these countries were not grants, but instead loans that need to be paid back. At the time of this writing, relations with all five countries have soured expressly because of OBOR to the point that China cannot trust any of them to serve as ports in any sort of military storm. (And that’s before one considers the general hostility of their neighbors—most notably India—to China mucking about in their neighborhood.) That leaves the Chinese with only one fully fledged foreign base: Djibouti. It is a facility over five thousand miles from China’s shores, designed to serve as an operational node to help multinational anti-pirate operations. It isn’t so much that the Chinese navy’s only overseas base exists to hunt half- starved black dudes in speedboats. The point is that China had to go so far from home to find a country poor enough with few enough preconceived notions about the Chinese that it would be willing to host a full Chinese base in the first place. Not to mention that ironically—hilariously—China’s Djibouti base is possible only because the Americans perceive it as helping uphold the lagging Order, and because Djibouti is so popular for anti-piracy bases that the Chinese hardly enjoy a strategic monopoly there: France, the United States, Italy, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates all operate permanent facilities in Djibouti.”

Well, what about its supercarriers?

“Much is made of China’s Liaoning . It shouldn’t be. On paper the Liaoning has perhaps one-seventh the combat capacity of a Nimitz [US’s first modern supercarrier]. . . and the Chinese didn’t build it. The Soviets did. In the 1980s. Sort of. This first-of-type vessel was never completed. After the Soviet breakup, the Ukrainians stripped it for parts. The ship then languished, rusting at dock for a decade until the Chinese purchased it. Today it is used purely as a training platform. China’s naval engineering is improving—the 001A , China’s domestically manufactured clone of the Liaoning, is undergoing sea trials at the time of this writing, but there are still decades of work to go before China can float something that can compete with a Nimitz . Carrier engineering isn’t rocket science. It’s a lot harder.”

But again, more important than merely being behind, China is inherently constrained by its geography:

“China is an inveterate land power that has fought major land wars with each and every one of the powers it borders. It simply cannot afford the sort of resource focus that made the British navy possible.”

Maçães on the other hand does at one point consider a US conflict with China at sea:

“…if the next few decades witness a naval conflict between China and the United States that conflict will more likely be centred in the Indian Ocean than the Pacific, thanks to its greater strategic importance, and in that case India and the Indian navy will be the decisive factor.”

Maçães seeks to better ask the question: where might a conflict take place, and what might swing the balance? For Zeihan, there is no question: US naval supremacy leaves no room for one. One of them seems to be wrong.

How important are carriers and today’s navies anyway? In his book How to Defend Australia Hugh White, a leading Australian defence strategist, doubts whether the navies Zeihan relies upon will even really matter in a major conflict:

“Warships will remain valuable for operations in waters that are not contested by other maritime powers, and likewise carriers and amphibious ships will remain useful in uncontested waters against less capable adversaries. But their roles in major maritime conflicts will disappear. Instead, war at sea will be dominated by submarines, aircraft, drones, missiles and satellites.”

Technology changes. Could navies be largely obsolete already? White is frank about the limits our knowledge today:

“…after many decades without major air or naval battles, we have little idea of how modern high-intensity combat will work, and which performance factors will make the most difference. For example, although huge sums have been spent on improving the stealth performance of fighter aircraft, no one really knows what difference stealth will make to the next great air-combat campaign. It might prove to be decisive, or to have been a waste of money.”

Technology advances and wars surprise. This is the challenges of Zeihan’s approach, which I’ll return to further below. But first: how Zeihan’s sausage is made.

3. Zeihan’s geographic determinism

Zeihan’s geographic determinism has a formula. Under a chapter ‘How To Be A Successful Country’, which uses China as its key counterexample, Zeihan outlines the four keys to success:

Viable home territories, with usable lands and defensible borders

A reliable food supply

A sustainable population structure

Access to a stable mix of energy inputs to participate in modern life

Grind a country through these layers and you will see how they will fare out in the wild when the US leaves its post. Take food, which under the Order has seen a “fourfold expansion in food cultivation since 1946 and thus also the tripling of the global population.” Per Zeihan, this has been possible because under the Order countries can import food from abroad or import the inputs required for food production to produce food themselves. Without this, “a billion people are going to starve”.

Again, Zeihan sees the point compounded in the case of China (it’s a long quote but worth it):

China faces a quadruple bind:

China’s margin of error starts razor thin, and not only because its lands are below subpar. One downside of China’s massive population is that the country has less farmland per person than Saudi Arabia.

As China’s population urbanized under the Order, much of the country’s good(ish) farmland was paved over, pushing Chinese farmers farther inland into ever-more marginal territories, which require more and more inputs to produce the same amount of foodstuffs. Unsurprisingly, the Chinese economic sector that is most dependent upon the expansion-at-all-costs financial strategy is agriculture. When the Chinese financial system cracks, not only will China face a subprime-style crisis in every economic sector simultaneously, but it will also face famine—even if nothing goes wrong externally.

On the surface, it appears China has sufficient oil and natural gas production to maintain domestic production of its fertilizer and fuel needs for its agricultural sector. After all, while China is a net importer of both fossil fuels, unlike most of Europe it still retains significant local production capacity. Not so fast. In any sort of constrained import environment—such as problems in the explosion-heavy Middle East—the Chinese will have to choose what they will let go of. Electricity? Motor fuels? Fertilizers? There won’t be enough to go around, and that forces choices.

China now isn’t simply the world’s largest importer of rice, barley, dairy, beef, pork, fresh berries, and frozen fish by tonnage. It absorbs more globally traded sorghum, flax, and soy than the rest of the world combined. The ongoing import of those products requires both the American Order and the ability of the wider world to produce the products in the first place. Unfortunately, it isn’t as if the Chinese are alone in this dilemma. Roughly one-fifth of the world’s agricultural produce is internationally traded, while four-fifths is dependent upon externally supplied petroleum-derived inputs, mainly fuel and pesticides. Remove the stability and shipping options and supply chains the Order makes possible, and many, many countries must figure out how to feed their populations with limited outside assistance. Most will fail.

Like I said: bleak.

Maçães assumes the rise of China from the perspective of its own dreams and aspirations. From the Belt and Road policy objectives, its historic parallels to the Silk Road that once bound Eurasia, and the perspectives of its political and academic classes, China’s assertiveness feels cautious yet determined. Maçães treats China’s threat to the US seriously:

In the same way that China and Japan had to change and adapt to the arrival of European civilization in the nineteenth century, the United States is feeling the impact of China’s unique takes on modernity and capitalism.

…the United States has much to lose in its relationship with China, where differences in the respective political concepts and increasing parity in economic power pose distinct threats. But then there is also much to gain, as shifts in position from Beijing can help the United States solve many of its security and economic challenges.

This seems in line with predominant view of China in the West today, which is viewed with a mixture of suspicion and awe. It is in direct conflict with Zeihan’s insistence that the Chinese threat is wildly overblown. Maçães elicits the wonderful texture of a nation through a local eye and a diplomat’s intimacy with political process, but some of his allusions to grander arcs of history appear presumptive. His objective isn’t quite as narrow as Zeihan’s geopolitical forecasting, of course. He doesn’t put forward a comparable analytical model, and the kaleidoscopic approach he takes, with its cultural and political appreciation, is in some ways the point. But Maçães does stake out geopolitical claims: consolidation in Eurasia, the corresponding threat to the US. Is Zeihan a contrarian provocateur or does Maçães harbour uninterrogated establishment biases?

4. The Dawn of Eurasia

The Dawn of Eurasia is a gorgeous insight into the peoples and places of Eurasia, the supercontinent containing Asia and Europe. Maçães’ perspectives on the whole arise from a focus on the smallest of its parts. It is in places like Chechnya, Azerbaijan, and Kazakhstan, between the tectonic plates of great powers, that new landscapes arise and hybrids form. These places are both a source of intercontinental tension and gaps where peoples and countries have fallen out of memory. The mystical lure in his note on the Caucuses might also hold true of the others:

“the past is part of the present. The successive waves of new peoples, religions and beliefs created a human landscape resembling geological sediments…”

It’s in these layers and flows of people that he paints the future. The nature of Chinese dreams and the Russian spirit, Indian abstraction vs Western thought, the expansion of Europe across the world in a way that eluded Christendom. How these stories infuse the national ambitions of their peoples.

Think of all the important and still undecided international questions of the last ten years. Energy security. Islamic radicalism. Ukraine. The future of Turkey and its position in the global system of alliances. The refugee crisis. They all point to the borderlands dividing Europe and Asia and are a direct result of flows – of people, goods, energy and knowledge – made possible by the gradual decline or collapse of the barriers keeping the two continents apart.

Maçães’ journey starts in the Caucuses, which provides the first contrast to Zeihan: that of style as well as of character. Zeihan speaks of the Caucuses offhandedly as some beautiful but backward land of mountainous barbarians: “If it weren’t for the locals’ tendency to flay outsiders, I’d go backpacking there.”

Maçães, on the other hand, delights in the layers of peoples and languages and cultures – from the last Jewish village outside of Israel, to the gaudy marble city of Avaza, Turkmenistan. Zeihan’s backpacking evokes a loud (and occasionally sneering) American lambasting through foreign lands. (My time in the rugged mountains of northern Georgia was far more weighted to eating xhinkali (giant dumplings) than flaying). Maybe that’s harsh on Zeihan, maybe he wasn’t referring to Georgia, but instead to Dagestan or the Chechnyans? Well, Maçães has an entire chapter about his time in Grozny, where the Chechnyan Muslims live under Russian auspices, facing Europe. He leads us through the Azerbaijani borderlands, where the local Muslims are proud custodians of the last Jewish village outside of Israel, while maintaining hostilities with their Christian Armenian neighbours. He contemplates the role of contemporary art in Iran. He admires the quickly growing and evolving trading hubs on the Khazak / China border, that meld into a flow of goods and people, whether Arab, Chinese and Khazak. The Caspian Sea’s “energy resources are of great interest to Europe, China and Russia… it brings five coastal countries inextricably together, creates numberless variables of interdependency and forces them to cooperate, while at the same time bringing competition to a high pitch…” These crossroads, the revival and pollination across the ancient Silk Road is entirely the point. As Maçães is seduced by the ebb of peoples and histories, so he conjures a future where these ancient cultural and geopolitical titans naturally converge. The direction of history that united Europe into the European Union continues under the Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Belt & Road initiative. Eurasia rises.

There is a geographic determinism at play here also. Why shouldn’t the largest supercontinent with the most advanced civilisations on earth finally unite? Maçães does not directly contemplate this. China is indominable. Europe is not going anywhere. Russia is underrated. But perhaps more than some inevitable pull in their geopolitical futures is the sense that anything is possible, that the East has come so far and their will is so strong, that they will be able to make their futures.

Maçães is not only more hopeful about China. He approvingly cites a quote in the Financial Times about Britain: “does Brexit offer Britain new opportunities as an agile trading nation, ‘a giant Atlantic Singapore’? Is a Eurasian capital being born on the shores of the Thames?” Whereas Zeihan believes the British will be “supplicants with no other options, so the terms of American-British interactions will be wholly American-determined.” How will Britain be relegated to US vassal status? The end of the Order and Brexit condemn “the Brits to a multiyear depression.”

Where Zeihan’s future is “unavoidable”, Maçães’ is yet to be born, hopeful.

Maçães’ is a poetic vision, enthralled by its subjects. His world is ancient or futuristic, lost cities and lost peoples (Circassians and Khazars), forgotten cities (Astrakhan), cities remade into the gaudy image of men, cities of the future, cities full of spies and lovers and adventurer archaeologists and diplomats and wily traders. Maçães is part Odysseus, enchanting us with his own travels and the tales that surround them. On the Caspian:

Stepan Razin, that impossible combination of Cossack and a Caribbean pirate, who set out for adventure and plunder on the Caspian, endlessly tormenting the Russians along the northern shore and Persians in the south until his gruesome execution in the Red Square in Moscow in 1671.

Or when he recalls Neft Dashlari:

the first of the Caspian’s imaginary cities”, a “full city at sea with hundreds of kilometres of roads built on piles of landfill connecting different oil platforms, partially submerged apartment buildings hosting thousands of oil workers, schools and cinemas, hotels and even a tree-lined park.

Maçães’ travels lead to pithy insights such as: “modern culture so obviously shares the rootlessness that distinguished our distant nomadic ancestors,” gathered from contemplating the nature of modern Kazakh life.

Maçães is also entranced with the Eurasian landmass itself. The way lands occupy our minds may be a function of the shapes and textures of the lands themselves. Consider how Russia’s eastern empires have never been considered alien to Russia in the way that Britain’s had. Its contiguous land mass has cast them as a natural appendage. Similarly, Maçães refers to Halford Mackinder, who suggested that

the reason we never thought of Asian and Europe as a single continent is that seamen could not make the voyage around it.

Maçães draws a nation’s dreams and conceptions of itself from its novels and sci-fi, from its local fashionistas and traders. He footnotes, lots. He is in the detail, seeking to glean the future from this or that political speech or infrastructure project. Maçães is interested in institutions - their political endowments and governance mechanisms. Whether political and economic power reside in the Eurasian Economic Union vs the European Union. Considering the aspirations of the European Union to automate decision-making, for example, comes naturally to a former Secretary of State for European Affairs of Portugal who would have sat in on those governmental processes.

Zeihan doesn’t really footnote. Zeihan shows us his four-point toolkit, then applies it country after country. His prophesy reads like a game of Risk, with nations playing against each other on a board, their strategic virtues and vices tallied up neatly for review. There is no room here for a nation’s conception of itself, of seizing its own destiny, of its poetry and lust, no anecdotes of pirates and princesses. These are all details, implicitly subsumed in the tectonic incentives that will necessarily propel countries in predetermined ways.

Maybe Maçães is too much of a romantic, seduced by the possibilities beyond the steppes. Maybe Zeihan is too reductionist. A Star Wars vs Star Trek-like competition in visions.

5. Determinism vs Hope (or Diamond, Zeihan vs Thiel, Deutsch, Maçães)

Where Zeihan’s future is determined, Maçães’ world is one of open slather. They sit across each other over the determinate vs indeterminate conception of history. They are not alone. Maçães has Peter Thiel and David Deutsch as companions, who virulently contend that the future is for us to create. If Thiel yearns for an optimistic determinate society, Zeihan is a pessimistic determinate, foreseeing an inevitable decline in world affairs. Maçães is probably an optimistic indeterminate, if optimistic mainly by temperament.

Thiel and Deutsch stand against theorists like Jarred Diamond, who in Guns, Germs and Steel argued that Western civilisational dominance stems from the fruits of its geography – the landscape, domesticable animals, climates. These allowed some peoples to conquer seas and far off shores, while constraining others from the ability to build cities, grow populations, scale armaments and win. Zeihan’s thesis is a geopolitical extension of Diamond’s geographic deterministic thesis.

Deutsch, critiquing Diamond’s thesis in The Beginning of Infinity, contends that “[t]he conditions for a beginning of infinity exist in almost every human habitation on Earth.” This aligns neatly with Maçães. Maçães’ dwelling on the deeper questions of cultural motivation and possibility is connected to the sense of agency his hope implies. Deutsch considered that

mechanical interpretations of human affairs not only lack explanatory power, they are morally wrong as well, for in effect they deny the humanity of the participants, casting them and their ideas merely as side effects of the landscape.

That is why humans are entirely absent form Zeihan’s conceptions of state conduct, and at the heart of Maçães’.

6. How much of the future can anyone ever see?

In some ways, Zeihan is proposing his own theory of everything. Through his prism, he purports to forecast everything from a multiyear depression in Britain to “a sub-prime style crisis in every economic sector simultaneously” and famine at the same time in China. He is a little fast a loose with timing, and so perhaps the magic is in that elusion. (To be fair, on a podcast, Zeihan did call China’s demise for this decade). His forecasts regarding Britain post-Brexit is off, for now at least – the UK economy is doing remarkably well, despite Brexit doomsayers. Regardless, his theory of everything is a little suspect, stretching powers of prophecy across geography, demographics, finance, military strategy, global supply chains, infrastructure costs. If he were really that powerful, Zeihan would perhaps be more at home in a hedge fund (for all I know, he is). Or perhaps his powers are more relevant over a fifty year view, in which case, it’s just hard to know. The concern is summarised by John Kenneth Galbraith:

We have two classes of forecasters: Those who don’t know – and those who don’t know they don’t know.

Zeihan comes out of a career at Stratfor, which calls itself “an American geopolitical intelligence platform”. On Stratfor’s founder, Wikipedia notes that

[George] Friedman's reputation as a forecaster of geopolitical events led The New York Times magazine to comment, in a profile, "There is a temptation, when you are around George Friedman, to treat him like a Magic 8-Ball."

Can geopolitical forecasting be a function of style as much as of analytical skill? Well it certainly makes for a riveting story, and as others have pointed out, a story goes a long way, even if it is cause for suspicion.

Have there been historic attempts at this kind of prophesy? How many hits will Zeihan have, and how much of it will be chance over prescience? Could there not have been a Zeihan-like prophet over any period of the last 500 years? With all the geographic and demographic facts of the time, were the rise of the Soviet Union in 1917 or collapse of France in 1940 foreseeable?

Or take Britain, which many post-Brexit are wishing to oblivion. You can look at its success in COVID vaccine development and rollout. Or you can look further back at its singular resolution against the Nazi conquest of Europe in World War II. Which of those would have been predicted in advance?

Czechoslovakia’s own version of the Maginot Line was a geographic fact you could have bet on against German invaders – yet Czechoslovakia was dismantled by political means. It’s geographic fortitude and threat to German invaders became irrelevant.

Political machinations defy geographic facts. So does technology defy would-be prophets. Technology changes the landscape, shuffles the strategic deck. These changes are inherently unforeseeable, or at least their timing. So the Dreadnaught relegated Britain’s naval supremacy to obsolescence ahead of WWI. Or motorised warfare changed what was possible in WWII. Or countless other advances in small and large ways irrevocably changed military and civilisational landscapes over time, allowing one people to dominate another in new ways. This is another way in which Zeihan’s geographic essentialism, casting the world into the pre-WWII world of regional powers, is deeply pessimistic. It implies a fundamental stasis in technology. Would another commentator in any other period have been correct even decades out, let alone a century?

“This time is different” is a punchline in the finance industry. Because it’s never different, is the implication. Except, sometimes it is. Railways. Electricity. Combustible engines. The Internet. Maybe today we really have broken the bonds of geography. Maybe instant communication and the dawn of global, decentralised finance means new kinds of cities will emerge (or rather, be built, by new pioneers like Balaji Srinivasan). Maybe we still underestimate the Internet – much more has yet to move online. This vector in human history is new. It’s anti-geography – it’s everywhere. The closer we move towards this future, the further behind fall the inevitable. It’s unsurprising that Balaji disagrees with Zeihan, preferring to bet on humanity’s indomitable will to create its own future everywhere, and to leave the morass of US and global institutions in the past.

To the extent that Maçães is a prophet, he is less ambitious, his prophesy less potent. He can claim that he mainly outlines, in lovely detail, the blurring of lines on the world’s greatest supercontinent. And who can really take issue with that?

7. Reversion vs Evolution

One way to frame Zeihan’s thesis is that the post-WWII US World Order is an aberration in world history. As it recedes, so we will move towards a more normal state of nature – regional nation state competition. Ziehan’s twenty first century is bleak, as the world reverts to a bleak historic mean. The world leading to WWII was unending chaos, a realpolitik morass of national states rising and falling in a race for self-preservation and dominance. And even the destruction of the world and coalescing of forces behind the US and USSR into the Cold War was in some ways a continuation of that: localised proxy conflicts around the world that were really manifestations of two great powers doing battle.

And so, says Zeihan, this momentary blip in world history, where the seas are protected and global trade can flow, will recede. We will revert to a more normal world, of regional powers and local conflict, unfrozen from the stasis of global hegemony.

It’ll be less like the messiness of the early 2000s or the raw potential of the 1950s, and more a disastrous combination of the battle royales and displacements of the 1870s against the economic backdrop of the 1930s.

It is unsurprising then that Zeihan’s vision is such an analogue one. His twenty first century resembles the nineteenth, just with broadband and supercarriers. Game-changing technology gets a hand wave dismissal – artificial intelligence, or the kind that would matter, is nowhere. And that’s it. It all still comes down to geography. Infrastructure will still be prohibitive across African “stacked plateaus”. Brazil’s agriculture will still be sub-economic. Whatever liberal principles developed since WWII are for nothing or were window dressing to begin with.

Maçães’ future evolves rather than reverts. He proposes that “we need a word to refer to the world as it is rather than the world as it aspires to be” – and that word is Eurasia, and it is set to do “what ‘Europe’ did for the Europeans after 1815.” The world is evolving to its next phase, just as it arose from its prior state.

8. The Russian soul

If Maçães’ journey is part odyssey, his political wonderings recall Hannah Arendt. He whirlwinds through the histories of peoples and political philosophies, all tied with piercing insights, anecdotes and irony.

He prowls through the bowls of Russian historic originalism, overturning predecessors of Eurasianism, who tied Russia’s past and future to Asia’s, to the Mongols and the Turks. He paraphrases a Russian philosopher, referring to a “subterranean affinity of souls between Russians and the Turkic peoples of the steppes” – a very Russian conception of themselves. Arendt was dismissive of this self-conception:

…to an innocent observer (as most Westerners were) the so-called Eastern soul appeared to be incomparably richer, its psychology more profound, its literature more meaningful than that of the "shallow" Western democracies...Franz Kafka knew well enough the superstition of fate which possesses people who live under the perpetual rule of accidents, the inevitable tendency to read a special superhuman meaning into happenings whose rational significance is beyond the knowledge and understanding of the concerned. He was well aware of the weird attractive- ness of such peoples, their melancholy and beautifully sad folk tales which seemed so superior to the lighter and brighter literature of more fortunate peoples. He exposed the pride in necessity as such, even the necessity of evil, and the nauseating conceit which identifies evil and misfortune with destiny. (Origins of Totalitarianism)

Maçães ponders no less than the meaning of life and its relation to the state. He wraps novelists and poets and a nation’s spirit into its geopolitical direction:

[Russian poet Joseph] Brodsky thought it was to the credit of the dying Soviet government that it did not even try to evade, simplify or disguise the question [of how to live]. There was no answer, there is no meaning to life, and people had simply to live with that. As the novelist Victor Pelevin puts it in The Sacred Book of the Werewolf, the substance of human life actually changes very little from culture to culture, but human beings require a beautiful wrapper to cover it. Russian culture, uniquely, fails to provide one, and it calls this state of affairs ‘spirituality’.

The language of Zeihan’s prophesy can speak only to Russia’s demographics and geographic sprawl sending it inexorably into chaos. Maçães contemplates the organs of the state and their relation with power:

The state aspires not to overcome and replace chaos, but to nationalize it or, in other words, to acquire and enjoy monopoly of it.

Perhaps this added texture is just an indulgence. More likely, in such cultural excavations comparisons between the two do neither justice. Maçães is portending a new geopolitical future, but he is also doing a great many other things, including illuminating the very many puzzle pieces of disparate people with disparate histories. Prophecy for him is beside the point.

9. Lighting the path ahead

Neither book offers policy actions. Actions imply agency and do not fit Zeihan’s deterministic approach. Maçães savours the world more as it is than what it will be – what are particular policies beside the grand arcs of peoples and their dreams? Zeihan’s model is difficult to resist. Its weakness is precisely its strength: it cuts through the infinite strands of future possibilities and individual dreams to provide a holistic framework from which to assess a nation’s strategic position. From there, policy makers can form insights.

I have been unable to resist applying it to my home Australia for example, largely untreated in Disunited Nations, presumably for its irrelevance to world affairs. Australia would do very well against Zeihan’s four criteria: ocean girt, internally stable and food and energy self-sufficient as it is, albeit with a too small population.

As a tour de force through the world’s powers, their strategic positions and how they might unfold, Disunited Nations is exceptional. As prophesy, we shall see. But his warnings about darker days resonate uncomfortably. For me, as part of the generation raised through the golden 90’s and ‘00’s in the West, who believed history was behind them and its arc had bent for good to the justice of an iridescent, endless present, the ruptures in that fantasy align with the dusk of the US World Order. Whether or not it plays out in the way Zeihan describes, it’s hard not to worry that the lives of our children will be poorer and more fearful.

Maçães might give reason to be more hopeful, for the future is unwritten. Thiel might say of course the future may be dark, for it will be whatever we make of it. Deutsch would say, well, everything that is permitted by the physical universe is possible, we just need the right knowledge. Maçães may in the end be the real conservative – it is far from radical to bet on the super-continent and its resident great powers that dominated world history until relatively recently. At the heart of those lands or at their peripheries, eddy the stories and the peoples who will rise to the occasion or fall to be wondered over by future adventurers and storytellers.

I think Zeihan is right to discount the idea of a united Eurasia. Transport by water is far cheaper than transport by land and crosses far fewer borders of taxing authorities. Getting bulk cargo from China to Europe by land is incredibly expensive (as evidenced by the fact that nobody does it). For all practical purposes, America is much closer to Europe than China or India.