Like all truly imperial peoples, the Spanish did not bargain with alien civilizations and cultures they found; they struck them down. They were not sailors, merchants, colonizers, nor refugees; they were conquistadores.

The Spanish alone made a true empire in the Roman fashion, something not always seen. They did this because the Spanish alone of all Europeans possessed an imperial consciousness and past when the great navigators opened up the world.

T.R Fehrenbach

In 1494, following the voyage of Columbus and discovery of the New World, the Portuguese and Spanish Crowns drew a line on a map, slicing the world in two between them and launching the age of exploration.

This led to some of the most startling encounters in history. Men who had seen Rome and Constantinople marveled at the unprecedented beauty and scale of the Mexica capital Tenochtitlan. Powerful empires met men mounted on horses in glistening armour, trailed by hounds and explosive artillery, with awe and terror. With the help of native allies and diseases they brought from Europe, groups of such men — sometimes in the dozens, not more than hundreds at a time — conquered empires with tens of thousands or more warriors and millions of subjects. The adventures of these men could hardly have been more mythical. Like Odysseus and his men, they faced terrible perils: disease, starvation, floods, jealous rivals and ferocious native enemies. On their adventures, some were showered in the nubile natives of their fantasies and discovered more gold than they could have imagined. More met grizzly ends.

And the men who led these expeditions — men like Columbus, Cortés, Pizarro — had their names written into legend. They could have been forgiven for seeing their paths ordained by heaven: their timing was impeccable. Hernán Cortés ran into an empire decadent after catastrophic natural disasters were “cured” by the intensification of human sacrifice, and Francisco Pizarro met an Inca empire torn apart by dynastic feuding. Yet perhaps inevitably, in a kind of Achillean pact, these men ultimately met ignoble ends.

Despite their conquests and treasures and legendary travails against enormous odds, today these names aren’t heralded in the same valour as Achilles or Odysseus. Fernando Cervantes in his excellent and comprehensive 2020 history Conquistadores: A New History of Spanish Discovery and Conquest makes the convincing case that this partly reflects the politics and Christian discourse of the time, which vacillated with political factionalism and grappled with the moral case for subjugating foreign peoples who had never caused injury to a Christian. It also reflects the ascendency of the nation state in the last few centuries and the propaganda of Latin American revolutionaries, who adopted the nomenclature of statehood and the cause of an injured native population against foreign empiral overlords to forge national bonds.

The Spaniards did not find nations to be subdued but rather — as in much of Europe — kingdoms locked into endless internecine conflict. The large powerful empires they met like the Aztec Triple Alliance in Mexico and the Inca in Peru had formed out of their own brutal conquests. As a result, conquistadors consistently found indigenous allies resentful of incumbent subjugation, without whom their conquests would have been impossible.

In a mix of Christian principle and true imperialism, the Spanish Crown was genuinely concerned from the start about the welfare of its new subjects. The pragmatic murder of native royals, the impetuous administration of “justice”, and the mistreatment (including enslavement) of natives brought condemnation from the Crown as well as the Church. There is some law of the universe that the further away a polity is from a conflict, the more empathetic its posture. As with the Spanish Crown and its New World subjects, so with American North East liberals and the conflicts of the frontier and southern slavery, US concerns with Apartheid South Africa, and British concern with slavery around the world. The conquistadores, friars, and other administrators in New Spain maintained an ingenious posture with respect to ‘unreasonable’ demands from the far off Crown: the principle of obedezco pero no cumplo: ‘I obey but I do not implement’. A wonderfully sly construction where there was no question of defiance of the ultimate authority, merely a recognition that the demand must be based on incomplete information or without appreciation for the full context.1 And so continued whatever practice the local rulers wanted.

For three centuries after their conquests, the Spanish kingdoms in the New World survived with no standing army or police force and with no major rebellions. This is a remarkable fact and speaks to the successful management of native power structures and relatively peaceable rule. The new rulers were surely less demanding than the old. The ratio of Spaniards to Amerindians was 1:5000 in New Spain. Given this ratio, the fortresses and churches being built put no strain on the indigenous economy. Fehrenbach writes:

The demands of the Mexica, probably, had been more onerous, certainly in waste and blood. Previously, at least a third of the daily hours of the common people had been devoted to various religious ceremonies, and Meso-American agriculture, without plows or draft animals, was minimally productive. The Spanish introduction of the steel axe alone worked a technological revolution; in 1535 Amerindian Mexico was probably more productive than it had ever been. If masses of Indians were being dragooned for Spanish projects, these were no more expensive in terms of time and labor than the former pyramids.

This does not — as we shall see — mean that the hands of the conquistadores were clean. Like Odysseus and Achilles, they too could be brutal — both through mistaken paranoia and deliberate cruelty in excess of what was justified by their missions. Yet this brutality was nothing new in a land of militaristic empires, human sacrifice, and cannibalism. It’s a strange insistence of historical narrative to frame the Spanish conquests as that of one people by another, rather than the displacement of one elite by another. It’s difficult to mourn the ruling Mexica in Mexico or the Inca in Peru with their ornamental savagery. The Spaniards were indeed often greeted as liberators, which is hardly surprising.

Inscribed somewhere on the fabled Pillars of Hercules that flanked the Strait of Gibraltar — a symbol of sea navigation and the end of the known world — are the words Non plus ultra: “nothing further beyond”. In 1516 following the conquest of Mexico, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, at sixteen years of age, adopted the pillars and the motto for himself with one amendment. He dropped the first word to make Plus ultra: further beyond. In this act of imperial (and youthful) hubris, he summed up the spirit of the age, with imperial ambition no longer confined to Europe and the rekindling of dreams of heralding the return of God with the entire world under the aegis of the Holy Roman Emperor. Plus ultra remains the national motto of Spain.2

In Part I (this Kvetch):

Cortés and the Mexica

Tenochtitlan

Late empire decadence

Noche Triste – the ‘Night of Sorrows’

The fall of Tenochtitlan

Native allies

Treasure

Nubile maidens

Burn the ships?

God in Mexico

In Part II:

Pizarro and the Inca

Qualms of conquest

How heroes die

Spain as the true successor to Rome

1. Cortés and the Mexica

Tenochtitlan

Cervantes’s portrait of Tenochtitlan and the Spanish encounter with the Mexica emperor is dazzling:

As they approached the capital, Cortés formed his men into a procession, himself adopting an air of lordly gravitas worthy of a Renaissance potentate. Decades later, some Mexica nobles recalled the horsemen in armour, the infantrymen with drawn swords and lances gleaming in the sun, the crossbowmen with their quivers, the arquebusiers, the feathered helmets, the standard-bearers, and the thousands of indigenous allies, dressed and painted for battle and dragging artillery on wooden carts. The horses and dogs, in particular, filled the natives with fascination and wonder. But the sense of awe that struck the seemingly unperturbed ‘Caxtilteca’ was, if anything, even more pronounced. What now opened up ahead of them was like nothing they had ever seen.

In terms of size, both in extension and population density, no city in western Europe came close to Tenochtitlan. As they crossed the causeway into the city, the Castilians were staggered by the tens of thousands of canoes – some, like great barges, carrying up to sixty people – that dotted the vast lake, inevitably prompting references to the city as ‘another Venice’ or even ‘great Venice’ or ‘Venice the rich’. Progressing into the city, the Spaniards were astonished by the beauty of the many towers, all ‘stuccoed, carved and magnificently adorned with merlons, painted with colourful animals and sculpted on stone’, which seemed to one observer to resemble the enchanted ‘castellated fortresses’ of chivalric romance: ‘glorious heights that were a marvel to behold!’

Something of this sense of enchantment was preserved in what has been described as ‘one of the most beautiful maps in the history of cartography’. This was the map of Tenochtitlan printed in the Latin edition of Cortés’s Second Letter to Charles V, published in Nuremberg in 1524.

Cortés and his men were greeted by a group of splendidly dressed noblemen at the end of the causeway, a place called Acachinanco, and escorted into Tenochtitlan where, at long last, they came face to face with the magisterial figure on whom their lives now depended. Moctezuma appeared on a litter, borne by noblemen, with a baldachin of green feathers, fitted with jade and beautifully adorned with gold and silver embroidery. As the emperor stepped down from the litter, Cortés dismounted, wanting to embrace him ‘in the Spanish fashion’, but was stopped by the guards. Formalities were exchanged, Cortés presenting Moctezuma with a necklace of pearls, the emperor reciprocating with a golden one. The Spaniards were both awestruck and uneasy at their new surroundings. They admired their imperial host’s splendidly exotic plumed headdress, but the blue figure of a hummingbird encrusted on the emperor’s lower lip, his earplugs and turquoise nose ornament, and the jaguar costumes of the chief warriors, clashed sharply with their sensibilities. They were gratified by the thousands of canoes that had paddled to the edge of the lake to greet them, a spectacle remembered decades later by a foot soldier ‘as if it were yesterday’, along with rooftops crowded with ‘countless men, women and children’. Yet the Castilians cannot have failed to realize the hopelessly vulnerable situation in which they had unwittingly put themselves. If Tenochtitlan was a beautiful city, it was also one engineered for defence: the various stretches along the causeway were flanked by bridges of removable wooden beams. Used primarily to allow canoes to pass from one side of the lake to the other, their potential use for defensive purposes was equally obvious. So too was the fact that the Spaniards were, should the situation deteriorate, hopelessly outnumbered. In the annals of conflicting emotions aroused by unprecedented human encounters, this episode has few if any rivals.

This is how Fehrenbach describes how the capital of the Mexica empire struck the Spaniards:

Tenochtitlán, and even the market at Tlatelolco, was parasitic. It drew its metals, bright feathers, figbark, vegetables, tobacco, beans, and jade, and even its maize, from the myriad subject lands around it.

An aqueduct brought clear, fresh spring water down from Chapultepec, enough for all the people, and an efficient gravity sewer system flushed the city's wastes into the darkening, polluted lake. No contemporary city or capital had anything to match the Amerindian engineering in this respect.

The Spaniards lucky enough to see Tenochtitlán in its glory agreed that it was incomparable, and these men included soldiers who had seen Istanbul and Rome. They were awed by the very extent of the city, enormous by their standards, and fascinated by the color, activity, and variety of the bazaars. The Spanish were unimpressed by the enormous pyramids and stone towers; they came from a land of great, grim fortresses and powerful stone walls set high above the arid countryside of Castile. What caught their interest was the sheer luxury of upper-class Amerind life. The splendid gardens and placid pools, exotic with colorful birds and tropic fish, the sweet-smelling shrubs and carefully tended trees—there was nothing like this in medieval Spain or Europe.

Late empire decadence

Moctezuma ruled over a land with customs that sickened the conquistadores.

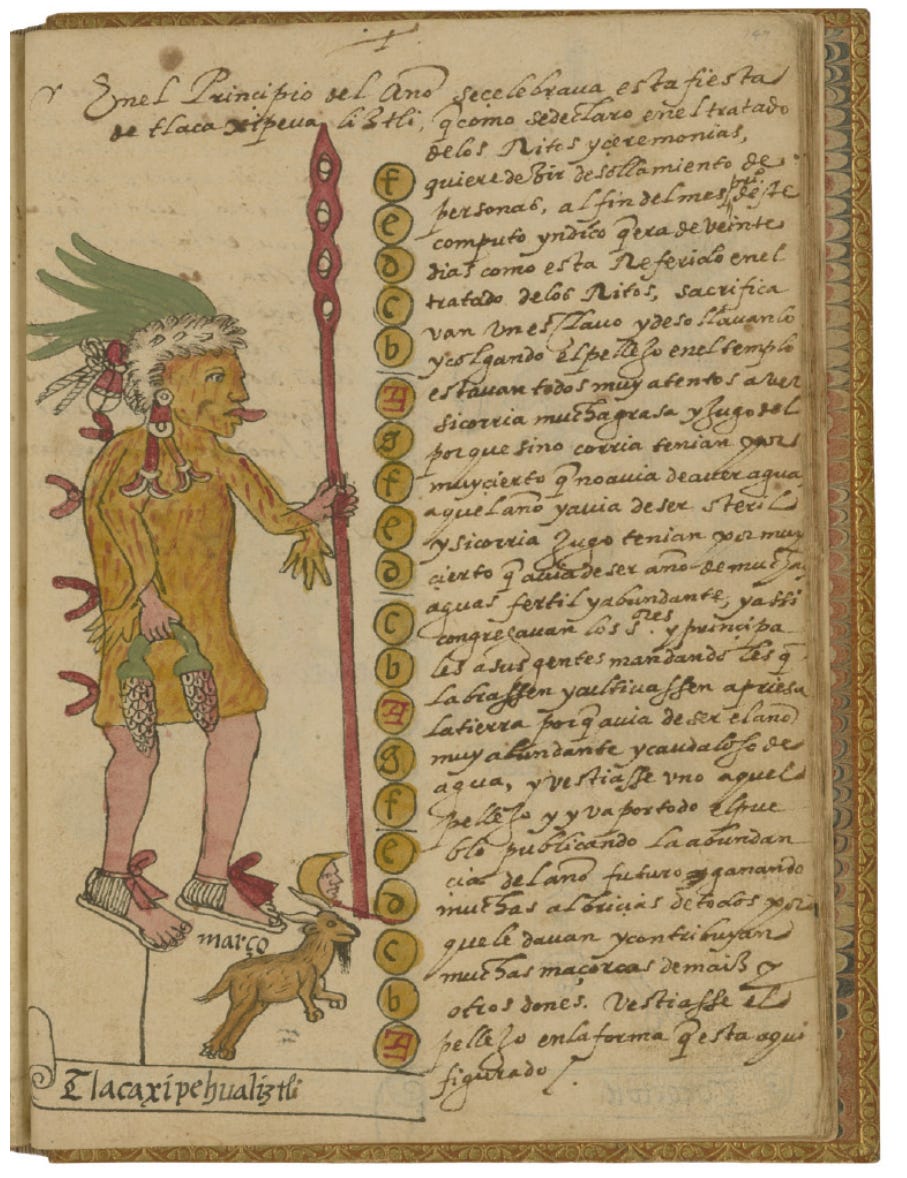

It was now mid-March 1520. On 14 February, I-Reed had become 2-Flint, and the propitiation of Quetzalcoatl gave way to the appeasement of the rain god Tlaloc in a series of festivals that involved the sacrifice of young children. This was followed by the month of Tlacaxipehualitzli, which runs from 6 to 25 March. Literally ‘the Flaying of Men’, it is illustrated in an early codex by the god Xipe Totec (literally ‘Our Lord the Flayed One’), depicted with a protruding tongue and a tunic made of flayed human skin. Some of the most elaborate ceremonies of the year were performed at this time, including gladiatorial contests and the wearing of the flayed skins of sacrificed victims who had taken the roles of impersonating the gods. Moctezuma himself was expected to wear one such flayed skin.

The Mexica had a tradition of flaying. The Mexica were not always dominant in the land. Much like the Comanche empire rose from meagre existence on the fringes of their world, so did the Mexica initially eke out a miserable existence on the fringes of Culhuacán empire centuries before the Spaniards arrived. Yet their fierceness found its uses (from Fire & Blood):

Coxcox, Lord of Culhuacán, permitted the tribe to hold some useless, snake-infested territory. But the Mexica apparently thrived on eating rattlesnakes, grew stronger, and erected a temple to Huitzilopochtli. The cultured Culhua, however, were disgusted at peculiarly bloody Mexic sacrificial practices.

But the Mexica were fierce, and thus useful, if disgusting neighbors. Culhuacán frequently warred with Xochimilco (“Country of Flowery Fields”), and Coxcox enlisted the Mexica tribesmen as mercenaries, promising them freedom from Culhuacán if they would capture eight thousand Xochimilca.

The tribe did so, and brought large bags of Xochimilca ears, cut from these captives, to Coxcox's throne. The pictographs showed Coxcox registering horror at these bloody trophies, but he kept his promise. Now the Mexica asked for a favorite daughter of Coxcox, that they might pay her a great honor. The ruler of Culhuacán was invited to attend the ceremony.

When Coxcox arrived in the Mexica temple, he found a Mexica priest prancing about in his daughter's skin; the girl had been sacrificed and flayed.

The society that greeted Cortes has recently convulsed: natural disaster struck the Mexica around 1450 (Fire & Blood):

After a serious drought, there were four consecutive years of snows and killing frosts; the normal seasons went awry. The corn supply failed, and the whole civilization was in danger of starvation. Such things had happened regularly in Mexico, but the Mexica tribal memory had no record of a disaster of such magnitude.

Up to that point, human sacrifice had been limited:

a few warriors were killed ceremonially to please the Sun, and a few virgins sacrificed to assure the sprouting of corn.

But in order to appease the gods in the face of these disasters:

Motecuhzoma mounted expeditions to the south and east to find thousands of new victims. According to the Mexica’s own records, the fury did not cease until ten thousand men were slaughtered at Tenochtitlan.

This sacrificial orgy was unparalleled in all of human history. And it seems to have spread over much of Mexico.

This led to Mexica civilization getting stuck in a kind of rut. A militaristic expansive society degenerated into ceremonial slaughter, culminating in the Flower War:

The final tragedy was that in Amerindian eyes this magic worked. Following the shower of hot blood the frosts ceased and the sun again warmed the earth. The corn flourished. The lords of Tenochtitlan took credit for averting disaster, and Tlacaélel urged the people to build a newer and more magnificent temple to Huitzilopochtli. And from this time forward mass ceremonial murder was not only institutionalized but uncontrollable. The rulers could not have halted the practice had they wanted to.

This sacrificial ardor had effects beyond the destruction of human life. After 1450 the empirical nature of Mexica imperialism began to change. The ancient Tolteca militarism had been pragmatic in its struggle for predominance and power, but now the Mexica armies tended to see the purpose of warfare more and more as a search for sacrificial victims. The warrior who took four live captives was honored over one who merely killed four enemies in combat.

The perversion produced one unique manifestation. This was the development of the so-called Flower War. The Mexica met both their enemies and their subject cities in prearranged ceremonial battles, whose sole purpose on each side was the seizure of prisoners for sacrifice. The Mexica fought these especially with Tlaxcala, Cholula, and Huexotzinga. A Flower War ended by agreement when one or both sides had taken all the victims it needed or desired.

The Flower War was a perfect manifestation of late empire decadence. Less deadly than a typical war, it disproportionately spared nobles, who were usually returned if captured, and had the purpose of exchanging sacrifice victims for both sides in the form of captures commoners. It was made for internal performative purposes. If war is what founding empires engage in to win, Flower Wars are what inherited empires engage in when all sense of mission is lost, where ideology and state have become inbred and recursive and a priestly administrative class take over.

Noche Triste – the ‘Night of Sorrows’

The flower of the Mexica nobility was dead. Even the stones seemed to weep

All in all, some 600 Spaniards and several thousand Tlaxcalteca had perished. Of the royal gold they were carrying, there was no sign

Cortés and the Spaniards were bold: they took the emperor hostage and ruled through him. At one point, Cortés left for the coast to put down rival Spaniard conflict. While Cortés was away, the contingent he had left behind became tense, fearing they were being prepared for sacrifice. The tension led to disaster as they Mexica began an important festival (from Conquistadores):

When the festival began, therefore, the Spaniards were in a state of some anxiety. About 400 Mexica, holding hands, danced in large concentric rings. Fearing that an attack was imminent, Alvarado instructed his men to block the three entrances of the main square: the gates of the Reed, the Obsidian Serpent and the Eagle. When the gates were closed, Alvarado and his men wielded their steel swords against the dancers and the priests who were playing the drums. The repellent scene was later recalled by the indigenous informers of Sahagún in ghastly detail: ‘The blood … ran like water, it spread out slippery and a foul odour rose from it.’ The Spaniards surrounded the dancers, and ‘struck off the arms of the one who beat the drums … and, afterwards, his neck and his head flew off, falling far away. They pierced them all with their iron lances, and they struck each with iron swords.’ Of one group of dancers, ‘they slashed open the back so that their entrails fell out’. Of another, ‘they split the heads, they hacked their heads to pieces. Their heads were completely cut up.’ Of yet another, ‘they hit the shoulders … they struck in the shank and in the thigh’. And if this was not enough, they attacked another group and ‘struck the bellies, and the entrails streamed out’. Soon the drums on top of the great pyramid began to beat: a call to all the men who had survived the massacre to go to the armouries located at each of the four entrances to the main square and launch a counter-attack. The Spaniards were forced to retreat… Outside the palace compound, the Mexica grew increasingly threatening. In a state of desperation, Alvarado ordered Moctezuma at knifepoint to call off the battle. But the Mexica emperor seemed to have lost his authority. Anyone seen taking food to the palace was put to death; several bridges were pulled up and the roads were blocked. At night the air was filled with the sound of lamentation. The flower of the Mexica nobility was dead. Even the stones, an indigenous source reported, seemed to weep.

When they returned to Tenochtitlan, Cortés and his men entered the city inconspicuously, noticing something was amiss.

The next few days were extremely tense… it was clear that the Spaniards had no other option than to flee the city. The retreat began in the dead of night. Muffling the hooves of their horses, the Castilians moved quietly through rain-slicked streets. Using a pontoon put together with beams from the ceilings of the palace, they crossed the first four bridges of the western causeway leading to Tlacopan. Then, as they were most of the way across, they were sighted and at once the drum on top of the main pyramid began to beat. Almost immediately, the lake swarmed with canoes filled with warriors firing arrows with a fury and clearly oblivious to the traditional Mexica tactic to aim to capture rather than kill. Those at the front of the column, including Cortés, managed to swim across to the mainland at Popotla. Cortés returned to assist the others, but the causeway was now under heavy attack on both sides and all the bridges were up. Those not killed by arrows were drowning, sinking with the weight of cannons and gold. The few who managed to reach the mainland no longer needed to swim: they crawled frantically over a multitude of corpses. All in all, some 600 Spaniards and several thousand Tlaxcalteca had perished. Of the royal gold they were carrying, there was no sign.

The fall of Tenochtitlan

Tenochtitlan ultimately fell through a combination of siege tactics to starve out its inhabitants — the city relied on outside sources of food and water — and the Spaniards’ local allies, who proved themselves in battle. Moving slowly through the city, they were forced to raze it to the ground to avoid entrapment.

Combined with the blockade, the effects on Mexica health and morale were devastating. As some native witnesses would later recall, many died of hunger. ‘No more did they drink good water, pure water. Only nitrous water did they drink.’ Many more had developed what they described as ‘a bloody flux’. In desperation they ate whatever they could find: ‘the lizard, the barn swallow, and maize straw, and saltgrass’. And they gnawed ‘colorin wood’ and ‘the glue orchid and the frilled flower, and tanned hides and buckskin, which they roasted, baked, toasted, cooked, so that they could eat them, and sedum, and mud bricks which they gnawed’. Meanwhile, the Spaniards advanced ‘quite tranquilly’. They ‘pressed us back as if with a wall; quite tranquilly they herded us.’

In the next few weeks the city was systematically destroyed – a process punctuated by a number of brutal surprise attacks in which hundreds of Mexica were killed. According to Cortés, this allowed his Tlaxcalteca allies to ‘dine well, for they carried all those that had been killed, sliced them into pieces and ate them’… Cortés would later recount to Charles V, ‘nothing else was done save the burning and razing to the ground of all the buildings, the sight of which in truth filled us with pity, but having no other option we were forced to continue’.

Native allies

After the defeat of the Mexica, the conquistadores continued south. The scale of ally support through the campaigns in Central America cannot be understated:

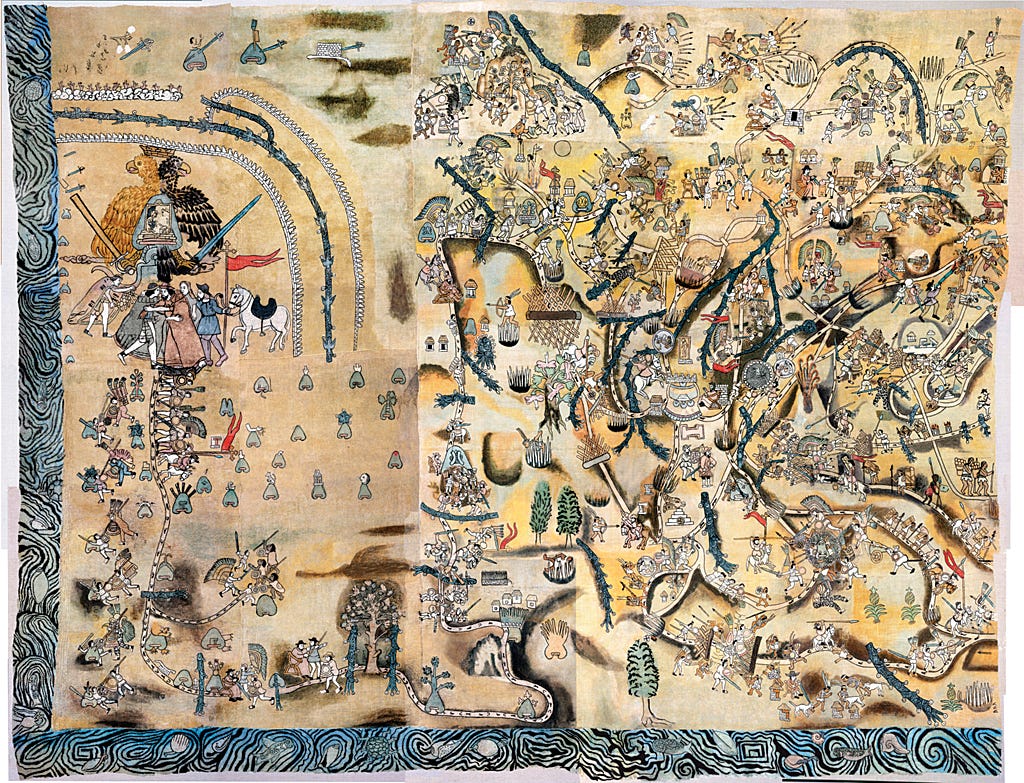

What most sources do not highlight is the scale of Nahua participation in the wars against the Kaqchikel – and, significantly, the increasing involvement of other Maya peoples against their detested former Kaqchikel overlords, whom they now took the opportunity to eliminate. These ‘native conquistadores’, as they have been called, played far more than a merely supportive role: they consistently outnumbered the Spaniards by at least ten to one, and on occasions by as much as thirty to one. Indeed, many battles were entirely indigenous engagements. In the fascinating pictographic account known as the Lienzo de Quauhquechollan, the Guatemalan campaign is presented by the Nahua participants as a joint enterprise based on an alliance of equal partners, Spaniards and Nahuas, with the latter depicted throughout the painting as conquerors in their own right. Especially significant is the appearance, in the top left-hand corner, of a clever reinterpretation of the Habsburg coat of arms, depicting the conflation of Spanish and Nahua forces shown by the two swords – one Spanish and one Nahua – clasped by the Habsburg eagle. Immediately underneath is a depiction of a friendly embrace between a Spanish conquistador and a Nahua chief. Flanking them is another Spaniard, most probably Jorge de Alvarado with his indigenous wife, and a native lord presenting the gifts that symbolize the alliance. As the campaign sets off, Alvarado is depicted alongside four Nahua lords who, like the Spaniards, are incongruously but significantly painted white – a clear sign of the equality of the alliance. In the rest of the lienzo – Spanish for ‘canvas’ – the Nahua allies are all painted white; and, in the depiction of the various battles, it is again the collaborative nature of the enterprise that is highlighted. The lienzo, in short, is an apt reminder that any opposition to the Spanish, however fierce, would never be strong enough to overcome the pointedly local sense of identity that characterized the indigenous peoples. This was something, of course, that the Spaniards were never slow to realize. They knew from the start that any thought of conquest would be chimerical without indigenous support and the possibility of forming local alliances wherever possible.

Treasure

The treasure Cortés reaped was great, even if it did not all manage to make the crossing back to Spain:

Cortés had extracted a fair amount of treasure from Cuauhtemoc: indeed, with his third letter to Charles V, dated 15 May 1522, he had sent a colossal amount of treasure: 50,000 gold pesos, a wealth of jewels, plenty of jade, large quantities of assorted gifts for a range of dignitaries, churches and convents, three live jaguars, and even some bones of alleged giants...3 Had the treasure reached its destination, it would have caused a sensation – but it did not.

The crossing was disastrous. At one stage one of the jaguars escaped, killed two sailors and badly mauled a third before jumping overboard. Then, on the way to Spain from the Azores, the fleet was attacked by Jean Fleury, a French pirate from Honfleur operating under the command of Jean Ango of Dieppe. Ango had been lying in wait for Cortés’s ships since hearing about the treasures shown in Brussels in 1520. He had probably also been inspired by King Francis I’s scornful remark that the papal grants to Spain and Portugal could in no way prejudice third parties: ‘I should be very happy to see,’ the king allegedly exclaimed, ‘the clause in Adam’s will that excluded me from my share when the world was being divided.’

Nubile maidens

The Spanish normally were offered a surfeit of nubile maidens wherever they went without demanding; from Cortés' first contact with friendly natives the Spanish march was a long debauch

It was not just the promise of treasure and gold that stirred the Spanish heart onward. The promise of nubile maidens seemed as much of a lure. Here is Hernando de Soto, launching an expensive and ultimately miserable campaign into Florida, and making his way all the way up to Arkansas.

The emperor and his advisors were well aware that, in the intervening decades, the region had become a haven for French and British pirates who preyed on vulnerable Spanish vessels passing the coastline of Florida as they rode the Gulf Stream back to Spain. For Soto, the region had clear attractions: not only was it believed to be the location of the fabled city of Cíbola, with its enticing golden treasures, but the scholar Peter Martyr, writing about the adventures of Ponce de León, had also portrayed it as an earthly paradise, populated by women whose bodies never aged and fountains of rejuvenating waters.

This was not always so fantastical, with the campaigns through Peru and Mexico yielding endless gifts of women from local rulers. For example, on the way to Tenochtitlan, in Amecameca, Cortés and his men were:

well received, fed, and presented with gifts of gold and forty slave girls.

This lasciviousness was the basis of a trap for Soto’s expedition through Florida:

the Spanish entered Mabila to a festive reception, ‘with many Indians playing music and singing’. Distracted and seduced by the beauty and grace of a group of dancing girls, the Spaniards did not notice Tascalusa’s swift escape into a hut, where his allies were planning an attack. From there he gave the order to kill all the Spaniards. It was only now that Soto and his men realized all the houses in Mabila were full of Atahachi warriors, who swarmed into the streets brandishing longbows, maces and clubs. There were thousands of them, and they caught the Spaniards unprepared and on foot. Many were struck down by arrows or crushed by maces. In the chaos Rodrigo Ranjel managed to fight his way to a horse across the plaza and to rear it up against the warriors, forcing them to pause long enough for Soto to do the same. Once mounted, Soto was in his element. He battled his way to the gate, allowing the few Spaniards who survived the attack to escape and raise the alarm among the rest of the army, which lay in wait on the bank of the Alabama river. The majority, however, were native auxiliary troops – including the 400 servants that Tascalusa had given them a week earlier. Realizing what was going on, they quickly abandoned the Spanish and convinced a good number of Timucua and Apalachees to do the same. To add insult to injury, they took with them all the Spanish equipment, clothing and provisions.

(Notice, again, the enormous advantage of horses.)

Fehrenbach is very firm on the question of native lovers. File this one under “things you probably can’t write today”.

The aura of rape that hangs over the conquest, however, ironically stems more from European attitudes in modern Mexican minds than from trauma visited on the Indians. The sedentary peoples lacked such European sensibilities. The Spanish normally were offered a surfeit of nubile maidens wherever they went without demanding; from Cortés' first contact with friendly natives the Spanish march was a long debauch.

Burn the ships?

One of the most famous moments in history is Cortés’s no-going-back moment of burning of his ships well summarised by Fehrenbach:

Mosquitoes drove the idle Spaniards mad, and thirty men had already been killed by tropic fevers. Cortés was urged to sail back to Cuba—but he had other plans.

Before his force quite knew what was happening, he set fire to his fleet. Now, there was nothing for the army to do but strike inland. On August 19, 1519, with forty Cempoalteca warriors, two hundred native bearers, and about four hundred Spaniards, Cortés left the beach. In the whole history of mankind, probably, no more audacious march has ever been made.

Yet, Cervantes — writing almost 50 years after Fehrenbach — has a different take:

Cortés could barely afford to dither. The suspects were court martialled under Cortés’s eagle eye: some were hanged, others scourged, one had his toes cut off. Then, to end any further defeatist talk of returning to Cuba, Cortés ordered the masters of nine of the twelve anchored ships to sail them aground. To ensure that they were entirely unseaworthy, all the rigging, sails, anchors and guns were removed, and the materials used to build houses in the new town of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz. In time, this astonishing decision would be compared to Caesar crossing the Rubicon; years later, Cortés’s lawyer would refer to it as ‘the most remarkable service rendered to God since the foundation of Rome’. It is not difficult to see why. Now there was only one viable option open to Cortés and his group of explorers: ‘to conquer the land or to die’.

Wikipedia agrees with Cervantes:

There is a popular misconception that the ships were burned rather than sunk. This misconception has been attributed to the reference made by Cervantes de Salazár in 1546, as to Cortés burning his ships. This may have also come from a mistranslation of the version of the story written in Latin.

2. God in Mexico

In a kind of ultimate Pascal’s wager, the Mexica took well to the Christian God. There was nothing strange about the adoption of new deities. In fact, it seemed only prudent. The Spaniards did indeed appear blessed with strange forms of power and beasts — why not curry favour with their gods? They did not appreciate that theirs was a jealous God and the Mexica idols an affront to these men.

One Andrés Mixcoatl was apprehended in 1537

while wandering through the villages of the Sierra de Puebla, distributing hallucinogenic mushrooms and demanding to be worshipped as a god. During his interrogation, Mixcoatl agreed that he had been deceived by his friend, the devil… what the neophytes saw was a further deity that they could, and should, incorporate into their pantheon. Indeed, if, as the friars insisted, it was the devil to whom the sacrifices were offered, then the indigenous ‘apostates’ would not have failed to see him as a crucially important ally.

Just like Boniface adopted the pagan symbols and traditions in Germany as Christian trophies, so did Christian emissaries in Mexico:

the dreaded cuauhxicalli – the sacrificial stone upon which many beating human hearts had been deposited – [become] the baptismal font of the new cathedral: there was, after all, something truly ‘sacramental’ in the rituals of pagan religions, where many intimations of Christianity could already be discerned. Even the Jesuit José de Acosta, who in the late sixteenth century penned the most damning condemnation of pre-Hispanic religions, asserted that ‘on those points in which their customs do not go against religion and justice, I do not think it is a good idea to change them; rather … we should preserve anything that is ancestral and ethnic as long as it is not contrary to reason.’

In any case, Christianity was spread successfully by the hard work of quality missionaries (Fire & Blood):

Indigenous needs and the qualities of Hispanic Catholicism do not quite explain the fantastic progress of the new faith in Mexico. A great deal was due to the quality of the missionaries. The Spanish clerical orders had been recently disciplined and purified by Queen Isabel and were at the height of their organization and élan. The friars of the regular orders, Franciscans, Augustinians, and Dominicans, were anything but refugees from the world—they were active, intelligent, dedicated men who expected to perform active roles in the world. They went barefoot among the people; they taught at the greatest universities. The priests and brothers who volunteered to take the dangerous passage to the New World in the service of their God were neither a cloistered band nor the still-ignorant, medieval-minded parish clergy of hinterland Spain. The friars of the century included men who had been soldiers, lawyers, farmers, and bureaucrats. The orders were meritocracies in which noblemen, the middle classes, and peasants' sons all found excellent careers. They were bound to discipline and austerity but at the same time forced out into the world and into vast affairs. In a society and an era suffused with great faith, they were the best among the best. Their coarse robes and simple habits, their keen knowledge of the true world, their erudition, and above all, their demonstrated humanity and burning convictions could not help but make immense impressions upon the Amerindian mind. The friars themselves, in their humaneness and humanism must have made a more profound impression than their theological arguments.

In 1531 the Virgin Mary appeared to a poor indio, speaking in the native tongue. From that time forward the Lady of Guadalupe was the patron of Mexico.

In the next fifteen years, nine million Amerindians were baptized. This work was carried out by a mere handful of men… In 1524, only fifteen Franciscans were in New Spain... there were not more than two hundred Franciscans in Mexico after twenty-five years.

In the sixteenth century Spain became the greatest civilizing power since Rome.

This is Part I of a two part series. If you liked this kvetch, you may like this review of The Verge, and of Tom Holland’s Dominion in Is Christianity The Air We Breathe? And if you want to go really esoteric on modern culture: The Heroes We’re Allowed.

Cervantes writes:

It was so effectively deployed that it was incorporated into the laws of the Indies as early as 1528. It furnished the conquistadores with an ideal mechanism for containing dissent and for giving time for reflection to potentially confrontational groups. It also, of course, allowed them to continue to enslave indigenous peoples for local use and even to ship them back to Spain, where scattered complaints about non-compliance with royal edicts can be found as late as the 1540s.

The defiance in the inversion of the motto is powerful. A modern analogue might be: move fast and break things.

Who knows... I have kvetched before on the prospect of ancient giants…

I like Daniel Kokotajilo's take on the conquistadors, showing that some of the common explanations for their success can't actually explain just how successful they were:

https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/ivpKSjM4D6FbqF4pZ/cortes-pizarro-and-afonso-as-precedents-for-takeover

I didn't read her name here. There was no one more important than Malinche. An Indigenous woman who acted as interpreter and advisor for Cortes between the warrior chiefs, including Moctezuma. Mother of Cortes' child, first of the mixed race Euro-Indigenous. Sold by her parents at a young age, then gifted to Cortes as an offering. She was intelligent, with a gift for languages. Cortes would take their son back to Spain. She died in what is now Mexico City. Long referred to as a traitor to the Mexican people. She is an incredible story. Largely forgotten, but a hugely important part of the conquest