On Liberalism's Aesthetic

Contra Cass Sunstein: Liberalism has a more muscular claim than just '60s nostalgia

Cass Sunstein has a new essay responding to becca rothfeld’s review of his book On Liberalism. Rothfeld argues that liberalism has an aesthetic whether it admits it or not, and that aesthetic is ugly. Not evil-ugly — just sad-ugly. Deflating. The aesthetic of a WeWork lobby.

Rothfeld inventories the liberal vibe:

chains selling salad bowls, mixed-use developments featuring glassy apartment complexes, the television show Parks and Recreation, the grocery store Trader Joe’s, the word ‘nuance,’ glasses with rectangular frames, group-fitness classes, the profession of consulting.

She argues that post-liberalism’s appeal is fundamentally an aesthetic aversion rather than an intellectual one. People aren’t reasoning their way out of liberalism. They’re getting bored out of it.

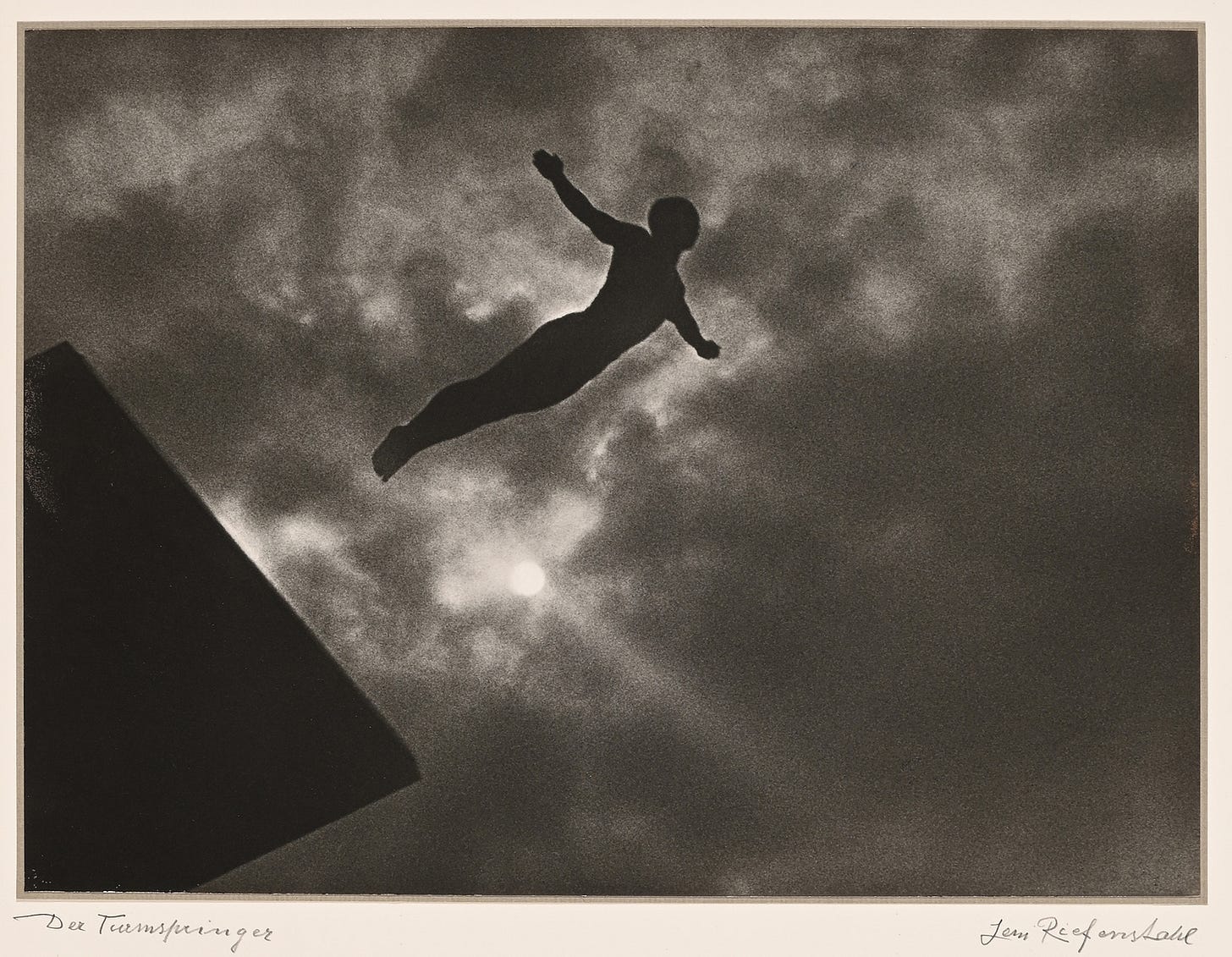

Rothfeld yearns for a Riefenstahl of liberalism.

Sunstein takes the hit with grace. He offers two responses. The first is that liberalism has no aesthetic — it’s about freedom, pluralism, and the rule of law, and if you want spiritual nourishment, look elsewhere. This has all the thumos of a castrated newt. I’m reaching for my state-sponsored euthanasia kit already. Reminds me of what my friend’s Soviet dad once told me when weighing career choices: interesting? If you want interesting, bang your head against a wall.

The second, which he clearly prefers, is that Bob Dylan is liberalism’s Riefenstahl. Bob Dylan’s Like A Rolling Stone is its animating energy, a celebration of freedom and openness.

Grim.

I like Dylan as much as the next guy, but reaching for a sixty-year-old rock song to answer ‘what does liberalism look like in 2026?’ proves exactly the point Sunstein is trying to refute. When the best aesthetic defence of your civilisational project is a track from 1965, you are not winning the argument. You are conducting its dirge.

The closest liberalism has come to a Riefenstahl in the last thirty years is Aaron Sorkin — the walk-and-talks, the soaring monologues, the fantasy of government as a workplace drama staffed by the smartest people in the room. Obama was Sorkin’s aesthetic made flesh: eloquent, composed, radiating a surety that the adults were in charge.

But the Sorkin aesthetic is part of the problem, not the answer to it. It was an aesthetic of competence, not of purpose. It celebrated the machinery of governance without ever being clear about what the machinery was for. And when the hopey-changey thing curdled, the aesthetic had nowhere to go. It ended in Gavin Newsom: a slimy suit with big white shiny teeth.

I’m sympathetic to Rothfeld, and agree that much of post-liberal anxiety stems from aesthetic and spiritual disappointment.

But there is more to the liberal aesthetic than Sunstein allows. Or there used to be.

Liberalism’s aesthetic bankruptcy is not a permanent condition. Salad bowls and rectangular glasses are not the natural expression of liberal commitments, the inevitable flowering of freedom, pluralism, and the rule of law. This would confound history’s liberals.

Rothfeld gestures to this. She invokes Trilling, she eulogises the Partisan Review, she distinguishes the humanist liberalism of Isaiah Berlin from the technocratic liberalism of a Matthew Yglesias. She knows liberalism once had texture. But her diagnosis remains, at bottom, Rawlsian. She accepts the procedural framework and asks how to make it beautiful. Her answer is intellectual pluralism — citizens as agents, arguing as equals, the crackling variegation of the Partisan Review. It's an attractive vision. But it mistakes the symptom for the disease. The Partisan Review was not beautiful because it modelled good procedure. It was beautiful because the civilisation that produced it still believed it was building something. The pluralism was a byproduct of confidence, not a substitute for it.

Liberalism did have an aesthetic, and for long stretches of the modern era, it was magnificent.

Think about what liberal civilisation actually built. The civic architecture of the New Deal: the WPA murals, the public libraries with their marble reading rooms, the Tennessee Valley dams that combined industrial ambition with genuine grandeur. Go back further. The self-portrait of a confident British civilisation in Turner and Constable. The Royal Navy patrolling the high seas against slavery. The great Victorian liberal institutions — the museums, the railways, the parliamentary buildings — were not exercises in procedural neutrality. They were assertions of confidence.

Go further still. The Enlightenment gave liberalism neoclassicism — an aesthetic that consciously reached back to the Roman Republic and Athenian democracy. Liberals once believed that free societies should look like they had inherited the earth. When Thomas Jefferson designed Monticello and the University of Virginia, he wasn’t being listless. He was building a visual argument for self-governance.

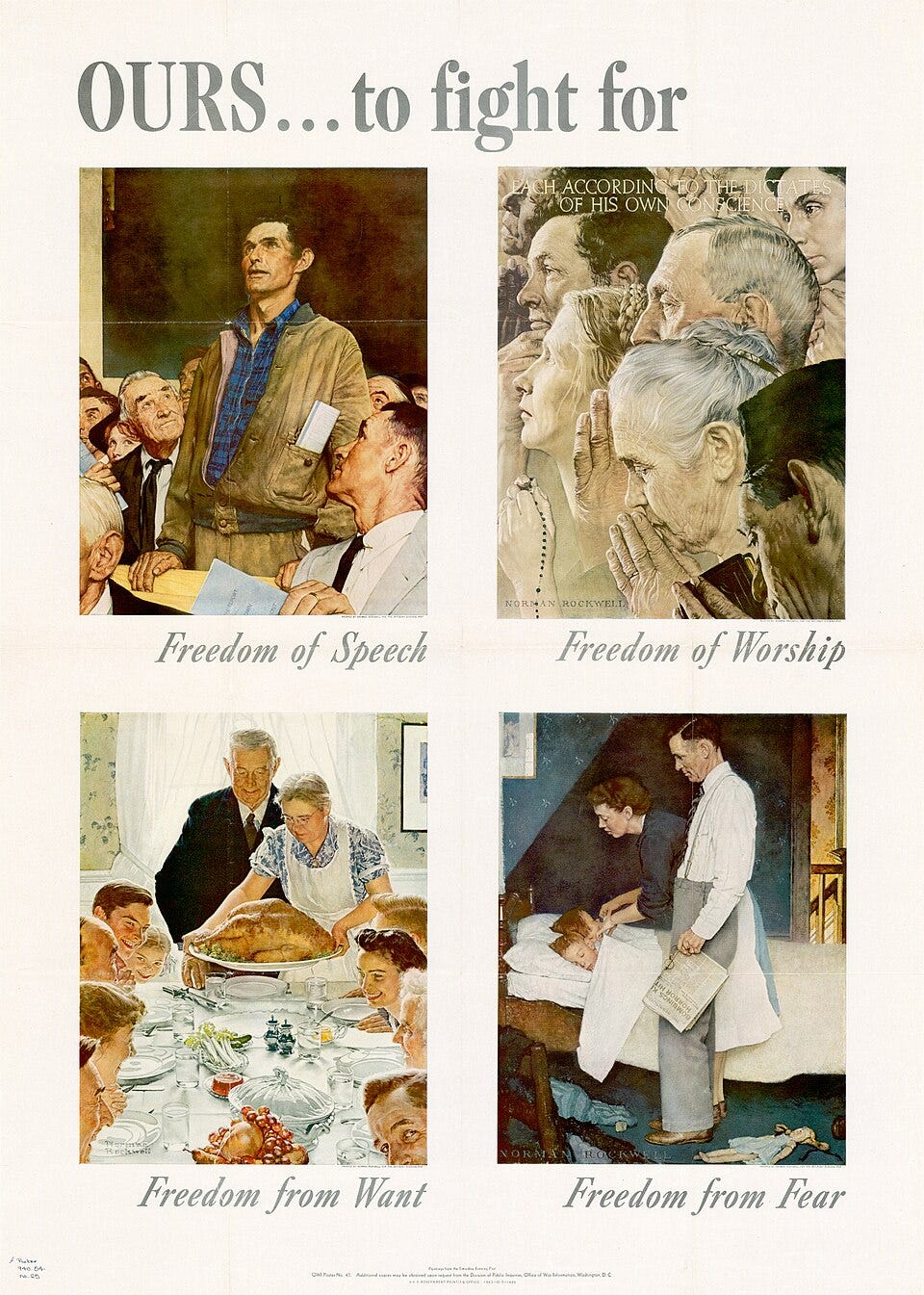

We need not go so far afield from music and art either. It's instructive that Sunstein reaches for Dylan, arguably the voice of 1960s America's cultural revolution from which Sunstein's sensibilities likely emerge. If we're looking backward, the truer candidate for liberalism's Riefenstahl is Norman Rockwell — the quiet image of an American protestant orderliness, and all the individual ruggedness and loneliness it entails. Rothfeld considers Rockwell and dismisses him. She sees him as conservative. But the ease with which today’s liberalism disowns Rockwell is itself a symptom of its emaciation. A liberalism confident enough to claim him — to recognise in his work the texture of the free society it had actually built — wouldn't need to.

The question, then, is not whether liberalism has an aesthetic. The question is when and why it lost one.

Liberalism’s aesthetic collapse tracks its transformation from a project into a procedure.

A liberalism that is building things — extending the franchise, electrifying the backcountry, constructing a welfare state, winning a world war — naturally produces beauty. It does so because it has two things that are prerequisites for any serious aesthetic: confidence and purpose. The New Deal murals are beautiful because the people who commissioned them believed they were doing something great. The post-war civic buildings are handsome because the civilisation that built them thought it deserved handsome buildings.

Something happened — you can date it roughly to the mid-1970s, though the intellectual roots go deeper — when liberalism stopped thinking of itself as a project with substantive goals and started thinking of itself as a set of procedures for managing pluralism. The shift was partly philosophical (Rawls, with his veil of ignorance, explicitly designed a liberalism that refused to endorse any particular vision of the good life) and partly political (the exhaustion of the Great Society, the stagflation crisis, the turn toward deregulation and market mechanisms as neutral arbiters).

This procedural liberalism actively selects against beauty. Beauty requires discrimination. It requires someone to assert that this facade is better than that one, that this public square deserves ornament and that one doesn’t, that some ways of arranging human life are more dignified than others. Procedural liberalism is constitutionally allergic to these judgments. It has convinced itself that any assertion of aesthetic hierarchy is a kind of coercion, that telling people some things are more beautiful than others is uncomfortably close to telling them how to live, which we must never under any circumstances do — anymore.

And so you get the built environment of late liberalism: the glass apartment blocks, the mixed-use developments, the open-plan offices. Ruthlessly optimised for function and neutrality, scrubbed of any quality that might suggest someone, somewhere, had made a judgment about what a good life looks like.

Rothfeld’s salad bowls are the logical endpoint of a philosophy that has decided the highest virtue is not imposing your taste on anyone.

This transition from project to procedure is also marked by a psychological shift from determinate optimism to indeterminate optimism. Liberalism once said: we shall build a great civilisation for our people! And now it whimpers: everything’s going to be okay?

One reason I suspect Sunstein struggles to reach for the muscular aesthetic of a bygone liberalism is because it wasn’t his textbook liberalism. You might call it a constrained liberalism. Liberalism was often contained within race nationalism or male dominance, assuming free society worked when it was run by and for landed white men. In the US, Woodrow Wilson, a giant of liberal politics, was all-in on a white America. In Australia, Frederic Eggleston, one of Australia’s great public intellectuals and an important liberal of his day, believed Australia’s Anglo-Saxon homogeneity was essential to its liberal democracy. These were broadly representative of their movements at the time. Liberalism for one’s people — defined as a racial civilisation — is arguably the oldest, and most generative kind of liberalism. That liberalism extended an island nation to dominate the world. That liberalism built America. That liberalism united Australian colonies into Federation. Today’s liberalism exists in the effete meanderings of public radio or the abstract philosophising of university professors.

The problem about the post-liberal aesthetic — the tradcath vibe, the muscular nationalism, the classical architecture mandates, the solemn invocations of beauty, order, and hierarchy — is not that they’re entirely nostalgic. All new movements and traditions borrow from the past, and in the process of returning, the best end up creating something new. The problem is that they have so far failed to be generative. They have not created great industry or built libraries or cities. They have barely slithered out of their corner of Twitter.

So what’s the answer? If I’m right that liberalism’s aesthetic problem is a function of its transformation from project to procedure, then the solution is obvious: start building again.

Not building in the narrow sense of construction, though that too. Building in the sense that the New Dealers and the post-war liberals understood it — as the physical and cultural expression of a civilisation that believes it is doing something worthwhile. A liberalism that was building high-speed rail, and nuclear power stations, and beautiful public housing, and great civic institutions would not need to reach for Bob Dylan to answer the question “what does liberalism look like?” It would point out the window.

There’s a reason Ezra Klein has discarded his low-T Ira Glass aesthetic, grown a beard, and written Abundance to wake liberalism from its stupor.

The Abundance people aren’t wrong, they’re just missing the aesthetic dimension, which is Rothfeld’s real insight. It is not enough to build things. You have to build things that are beautiful. You have to be willing to say that some buildings are better than others, that some public spaces are more dignified than others, that a train station can and should be a work of art (I am a big Sydney Metro fan).

When America’s founding fathers debated what image should be cast on the Great Seal of their new republic, Benjamin Franklin proposed Moses parting the Red Sea, Pharaoh overwhelmed by the waters, with rays from a pillar of fire reaching to Moses. Thomas Jefferson proposed the children of Israel in the wilderness, led by a cloud by day and a pillar of fire by night. These were not men afflicted by procedural modesty. They reached for the most grandiose imagery available to them because they believed they were doing something worth commemorating grandly. That instinct — the confidence to assert that your civilisation deserves magnificent symbols in the image of your tradition — is what liberalism has lost.

For a new aesthetic, liberalism need only recover what the FDRs and Robert Moses of yesteryear already had: the willingness to make judgments, to assert that some things are better than others, and to build accordingly. They weren’t in tension with American liberalism. They were its fullest expression.

There are Riefenstahls among us for those with eyes to see. Liberalism can elevate them to its needs. It need only will it.

Until then, enjoy your salad bowl.

I don't think the lack of bold aesthetics has much to do with "striving" or muscular or energetic anything.

Most of it is just plain old boring happenstances.

For instance, the sheer brilliance of 60s and 70s musical progression happened because of a confluence of things:

- electricity

- relatively cheap instruments/equipment

- the rise of individual expression coupled with how easy it was for a group of misfits to get together and just play

- the economics of seeing local bands, supporting their development

- cheap rent in cities

- the prolonged education of the youth and reduced need for doing actual work at a young age

- the relatively limited set of other options people had for entertainment

- recorded music being a massive money spinner

No one was striving or muscular or had a vision. It was just a confluence of things that enabled it to happen.

And when it comes to aesthetics, ordinary people are voting with their purchases: they want the bland Ikea look.

And more recently, Federation Square was built in Melbourne. It was bold, visionary, a statement; and it's absolutely fucking ugly.