Remembering my grandfather (repost)

יְהֵא שְׁמֵהּ רַבָּא מְבָרַךְ לְעָלַם וּלְעָלְמֵי עָלְמַיָּא

Republishing a post from 2 years ago commemorating my grandfather’s yahrzeit today.

Since then, one more great-grandson has been added to his line.

Today I commemorated by grandfather’s yahrzeit. He died nine years ago and would have been a hundred this year.

I wrote a bit about him here, and yes, it’s the same grandad who wasn’t too pleased with having three daughters and no sons. He was one of three boys, after all, and his brother had two sons. He was a loving grandfather, albeit stubborn and curmudgeonly — traits that run thick in my veins.

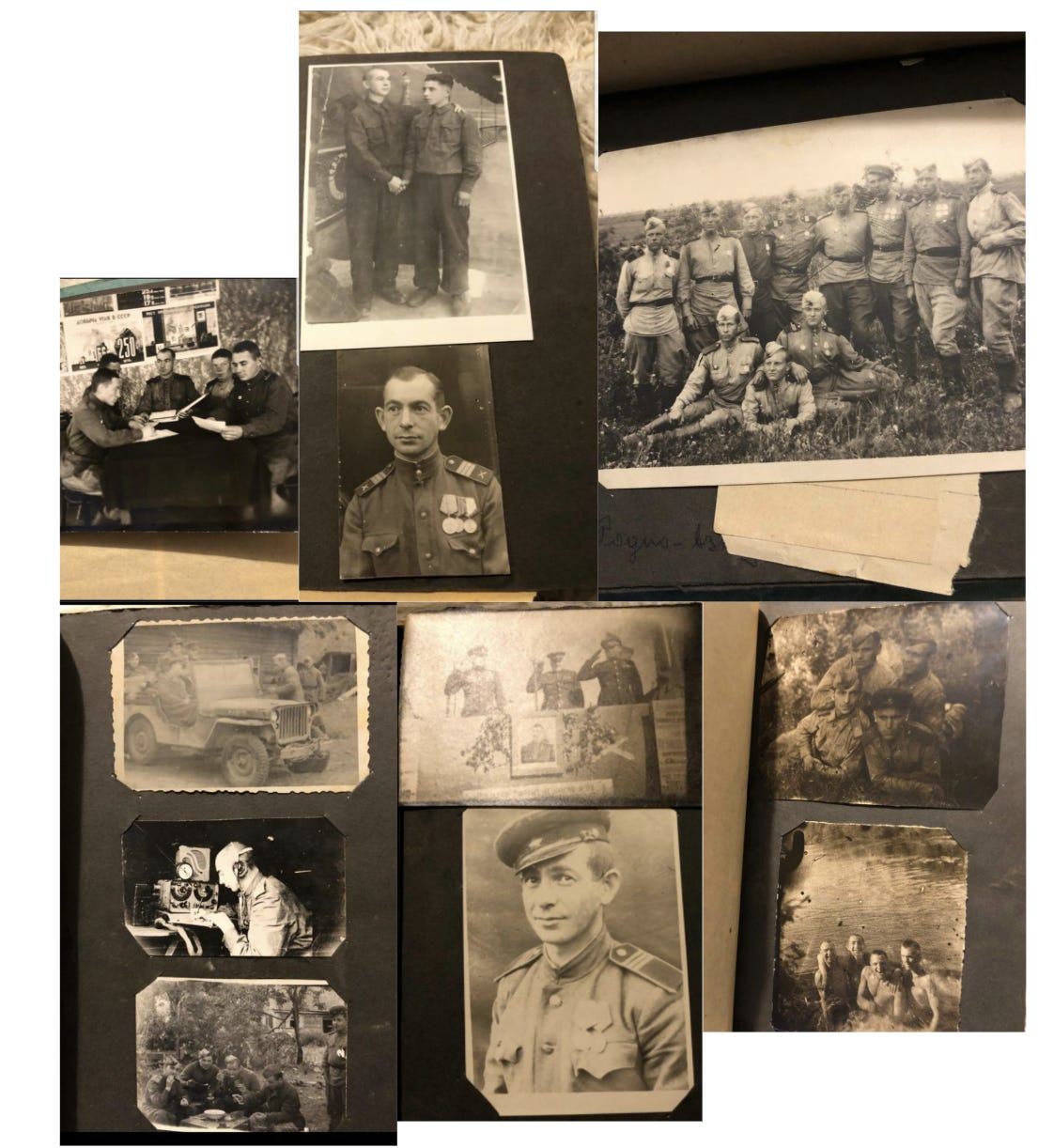

He had a hard life. My grandfather was one of the poor, cold, hungry Red Army soldiers encircling the German 6th Army as a part of Operation Uranus. He was eighteen and his brother sixteen when they left their village Gorodenko, in what is now Ukraine, ahead of the German advance (being able-bodied men). He joined the Red Army out of hunger — imagine that the Red Army in the Eastern Front was the better option. He didn't know then that his eleven year old brother and parents had been shot into mass graves along with the other Jews of their village.

Growing up his family ate chicken once a week on shabbat. After the war, in Tbilisi he was a barber. Cut the important people’s hair, my grandma tells me. He cut our hair when we were kids — right there in their kitchen. When grandma was first introduced to him, he met her wearing this big impressive hat. She almost fell over when he took it off to reveal his bald top.

This morning when I was explaining to my kids why today was special and we remember my grandfather, I explained to them, in somewhat less stark terms, the hard life that he lived.

My six year old boy, whose life is more fantastical than I could have ever imagined growing up, chimed in: “I also lived a hard life! People are mean to me.” (Buried in that sweet childishness lies a harsh lesson on the human condition and the relativity of our suffering.)

My grandfather’s yahrzeit falls on the first parashah of Vayikra — the Book of Leviticus. It’s a strange one to fall on. Perhaps Genesis would be more appropriate — his is a story of two brothers, after all. He did not share the more mischievous temperament of his younger brother Abram, who died before him. He was colder, more serious. Life seemed harder for him. Perhaps not quite as indicting as the fates of the older brothers of Genesis — Cain, Ishmael, Esau, Joseph’s older brothers — but surely as troubled.

Or perhaps Shemot, the Book of Exodus, after his own exodus first out of Galician Poland (now in Ukraine), then out of Georgia, amidst the ruins of the Soviet Union, to live and die in this blessed land, Australia. His name was even Moshe (Moses). Yet whilst life in Australia proved fortunate, it looked to me forunate in the way it’s fortunate that a salmon makes it upstream: it lays its eggs and dies. Old age brought loneliness and the endless blare of television, inching higher in decibels with the deterioration of his hearing. Waiting out the last decade of his life. Troubled by dreams of the dead. Exodus would be appropriate even here, Moses having died without entering the Holy Land, leaving the fruits of his toils to his descendants.

Yet, his death falls on Vayikra — Leviticus — the most impenetrable of Books, detailing the minutiae of Temple sacrifice. I have written before about the special place the laws of sacrifice hold in Jewish jurisprudence. There is no ‘why’ when it comes to these laws, as there is no ‘why’ when it comes to the laws of kashrut. They just are. The laws of sacrifice make up a big chunk of the 613 mitzvot, and are basically all rendered inoperative today in the absence of a Temple. Its laws follow their own idiosyncratic logic. The Sages actively question throughout their commentaries: what is this Book about? I once told my friend, a rabbi, that Genesis was my favourite Book. Pft, he scoffed. Genesis is everyone’s favourite book. Come back to me when it’s Leviticus. (Edit: I recently told this story to Tyler Cowen. And the case for Leviticus.)

And so here we are.

Yet, perhaps Vayikra, Leviticus, is entirely apt for my дедушка. Sacrifice. Inscrutability. From a time and place and generation for whom there was no ‘why’. Hier ist kein warum — here there is no why, a guard told Primo Levi at Auschwitz.

And so today in shul on my grandfather’s yahrzeit I repeated the mourner’s kaddish as required.

The repetitions of this ancient prayer in Aramaic are some of the more sombre moments during a service. The community feels in congress not only in that moment in that synagogue but stretching back thousands of years. That feeling permeates the entire service of course — in some ways it’s the whole point — but the commemoration of a loved one somehow brings to bear in that one mourner and that one memory the spirit of an entire people.

There is your own communion with the past. But there is also sharing others’ moments. A few months ago an elderly man I didn’t know wept as he said kaddish for his recently deceased wife. He turned to me, wiping tears from his face and said: I still love her in death. It’s unsettling to stare directly into such holiness.

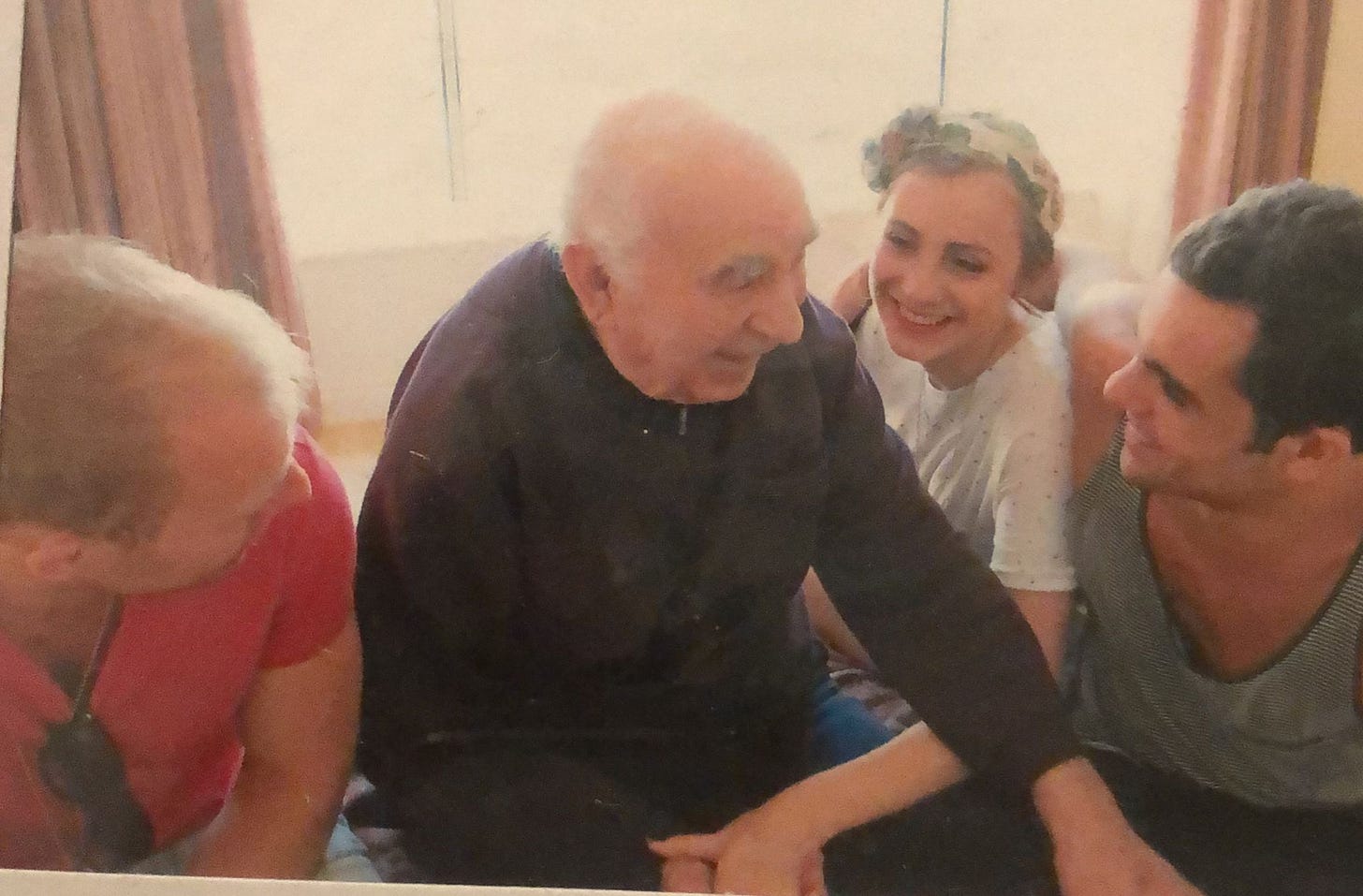

My grandfather left behind his wife — still powering on at ninety-three — three daughters, seven grandchildren and — so far — seven great grandchildren. The names of his murdered father and brother continue in my children’s names.

יְהֵא שְׁמֵהּ רַבָּא מְבָרַךְ לְעָלַם וּלְעָלְמֵי עָלְמַיָּא

May His great name be blessed for ever, and to all eternity

I read this 2 years ago I guess now. And I read it again. Your grandfather's memory is for a blessing.

A fortunate life - in the long run.