“Anything that needs to be done, remember this: my husband comes first, the girls second, and I will be satisfied with what’s left.”

— Claudia “Lady Bird” Johnson

In later years, when more details of her husband’s sexual affairs emerged, she would sometimes be asked about them. She finally evolved a stock reply: “Lyndon loved people” she would say. “It would be unnatural for him to withhold love from half the people.” And the reply was always delivered with a smile.

— Robert Caro, The Years of Lyndon Johnson

The story of Lyndon B. Johnson (LBJ) is the story of his all-consuming ambition. In service of that ambition he fed everything: his health, his principles, his relationships. His lieutenants never worked harder in their lives. He selected for loyalty above all else. Fealty to him. And in service of their leader, he worked them dry, squeezing from them everything they had, lashing them verbally with a rare gift for finding and piercing a man’s most vulnerable point. He left husks of them. Lieutenants recall both the fear of working for him — but also the satisfaction. Despite the humiliation and the harrowing conditions, it worked. By their admission, he wrung more out of them than anyone. And of course, he worked himself hardest of all.

This furnace of a man consumed not only himself and those he latched to his cause, but also his wife. Lady Bird is something of a rising star through the arc of LBJ’s career and life as told by Robert Caro in his multi-volume The Years of Lyndon Johnson1. We meet her as an able but exceedingly shy young woman courted by Johnson. She happens to be the latest in a line of prospects, all daughters of the wealthiest man in their towns. He courts her furiously and once he wins her, subjects her to the same grueling machinery of humiliation that governs the lives of all of his subordinates. We wince at his treatment of her (as we shall see). We peek through cracked hands at his open philandering. Yet she is not reduced to a husk. She absolutely subordinates herself to him — yet she grows steadily in stature. She deftly governs his congressional office while he is away at war in the Pacific. She is an admired and effective leader at the reins of their radio business. She protects and cares for him at his most vulnerable after his heart attack. Through his vulgarity, his humiliation, his bullying, she defends him and deploys her considerable talents to his cause. We first pity but come to admire her. What a wife. Truly God-tier.

“A modest, introspective girl gradually became a figure of steel cloaked in velvet.”

Through the Years of Lyndon Johnson we are privy not just to Lady Bird but, in the epochal manner of Caro, also to his mistresses. And let’s just say they’re God-tier too. I end this kvetch with Caro’s portraits of them, as they’re as lavish a portrait as any Caro paints.

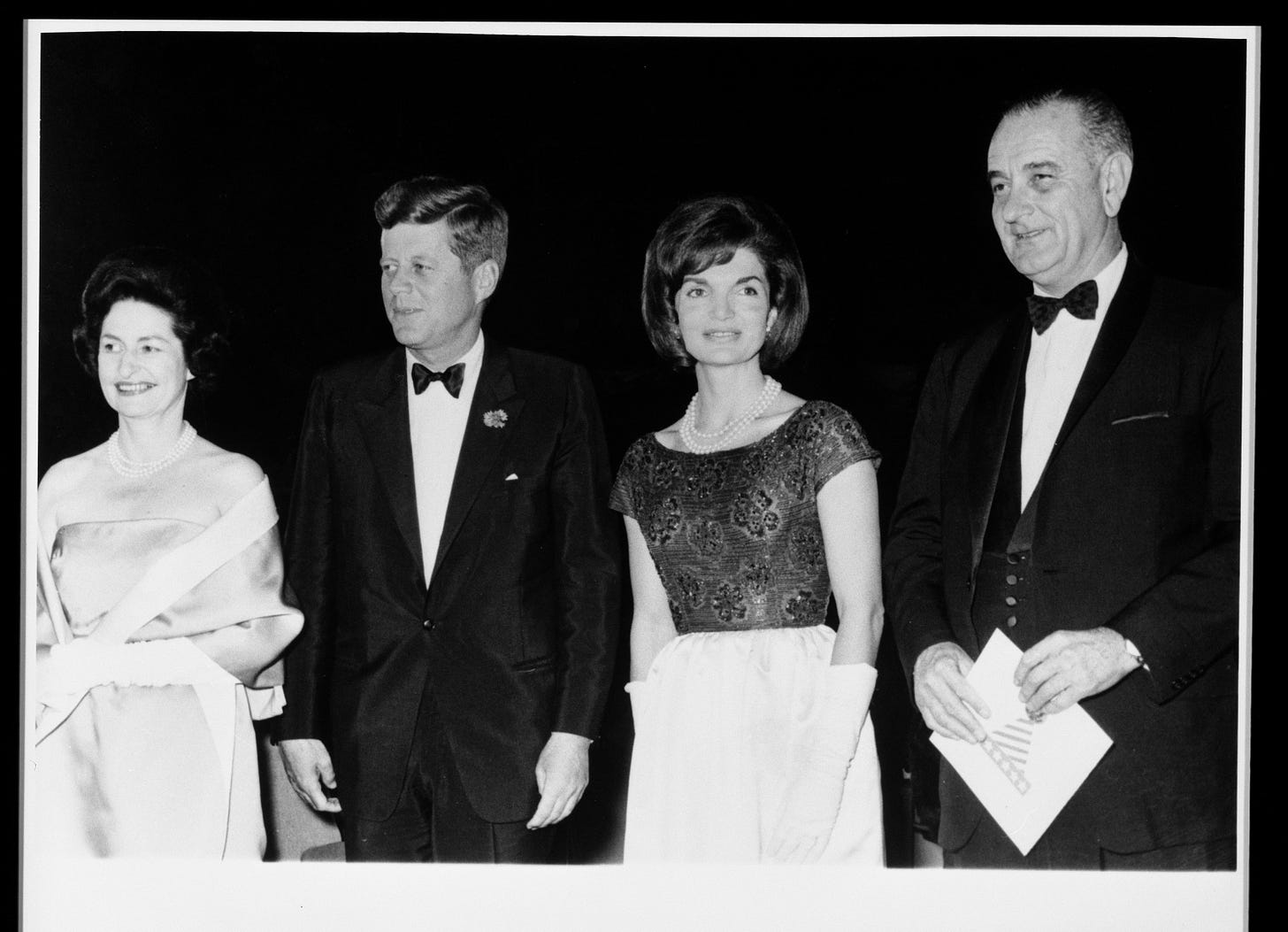

Lady Bird’s humiliations are not alone in Caro’s tale. Jacqueline Kennedy played the princess of Camelot while the White House teemed with her husband’s lovers. JFK, our hero prince, is off “cruising in the Mediterranean with two of his fellow pleasure-seekers” as his wife miscarries. His brother Bobby is by her side and arranges for the infant’s burial and her comfort. While Bobby drove through the night to be by his brother’s wife’s side, JFK “did not rush back”. Caro does not much focus on Jacqueline or the lovers. We only catch a glimpse. His tale is LBJ’s, and so JFK’s mistresses only pop up when LBJ literally knocks them over (like the “scintillating” Georgian Helen Chavchavadze who LBJ knocked over while dancing — he “lay on her like a lox”). One gets the sense Caro does not care to dig too much into this part of JFK, partly as it may appear voyeuristic, and partly as it’s unbecoming to this hero prince whose brains bespatter the latter parts of the story. But certainly as Jacqueline grabs at pieces of her husband and mourns his passing and stands stoically in the eye of a grieving nation, one does not get the impression of anything other than a loyal, steadfast wife. Something she shared with the timid and somewhat less glamorous Lady Bird.

JFK’s relationship with his wife is about as different to LBJ’s relationship with Lady Bird as his relationship with his men is different to LBJ’s with his. JFK doesn’t lash them, doesn’t humiliate them or make them cry. He inspires them. He engenders their love, and through their love their fealty. JFK and his brother were wary of the way LBJ left husks of his men, as if he sucked the souls right out of them. Yet both proved to be remarkable leaders of men.2 While LBJ hammers and bullies his message through people and radio however he can, JFK glides in with a joke and wink. So their ways with women.

Their story is also not one of the inevitable appetites and indulgences of powerful men. One of Caro’s most striking and poignant characters is the successful, charismatic, loyal and shockingly honest Coke Stevenson. And his love story is as wholesome and inspirational as LBJ’s and JFK’s appetites are voracious.

Breaking Bad’s Skyler White is an altogether different woman to the two former First Ladies, and her suffering different to theirs. And while we come to admire (and even love) Lady Bird and Jaqueline Kennedy, we loathe Skyler.

Whereas Lady Bird enters the frame as LBJ is long gripped by a furious ambitious, and Jacqueline Kennedy is the picturesque wife of America’s most charismatic chieftain, we meet Skyler White with her husband firmly ensconced in her grip. It’s Walt’s 50th birthday. She’s made him scrambled eggs with fake bacon as a treat — she’s monitoring his cholesterol. That night he gets the coup de grâce: a handjob she delivers while following an online auction on her laptop. She squeals with glee at winning the auction before he orgasms. It’s the end of the line for Walt. Maybe cancer can put him out of this misery.

Walt of course, breaks out of this prison. He breaks out of his domestication. He breaks bad. Cancer catalyses what he once had and lost: his will to power.

In episode 2, Skyler confronts him: he’s coming home late (from cooking meth), he’s acting weird. He fesses up to buying weed (which he’s not). A murderer trying to pass as a thief.

You don't come home last night until 2 in the morning. You don't tell me where you've been. You spent the entire night in the bathroom, Walt. Tell me what's going on with you. Don't you think you owe me that? Who is this Jesse Pinkman to you?

He sells me pot.

He sells you pot?

Marijuana, yeah. Not a lot. I mean, I don't know. I kind of like it.

Are you out of your mind? What are you, like, 16 years old? Your brother-in-law is a DEA agent. What is wrong with you?

Look, Skyler… I just haven't quite been myself lately.

Yeah. No shit. Thanks for noticing.

I haven't been myself lately but I love you. Nothing about that has changed. Nothing ever will. So right now, what I need... is for you to climb down out of my ass. Can you do that? Will you do that for me, honey? Will you please, just once, get off my ass? You know. I'd appreciate it. I really would.

He lives. No, he doesn’t owe her. He can buy weed if he wants to, he’s a grown-ass man.

As the pressure mounts, what does Skyler do? She leaves Walt. She takes the kids. She sleeps with her boss. She takes Walt’s cash and pays off her boss’s tax debts. Eventually she becomes his partner in crime. She helps him buy a car wash and manages his money laundering operation. She is a sharp bookkeeper and manager. Yet her soul is slowly crushed as Walt’s ascends. Their roles flip. Whereas he had been a subservient husband imprisoned in her suburban prison, she is now subordinated to his will, his thirst for power and empire building. He is no longer the horse with the bit between his teeth but the mounted warrior conquering the world. He’s undomesticated. Forget miserable handjobs — by the end of the first season he’s ravaging her in the living room and the car. And she hates it.

But it’s not her fault. Walt allowed himself to get screwed over by his early start-up co-founders (including his ex-girlfriend Gretchen), who went on to make a fortune off his genius. Skyler is a suburban Arizona wife: this is her world. He opted into that. She is not so much his jailor as the lady of the small middle-aged hell he fell into from his youthful heights of Great Promise. Rather than the beautiful and elegant and now-billionaire wife he was promised, he has the Lady of Suburbia who holds back on the bacon and doles out handjobs on special occasions.3 On the face of it, this is the life he chose. Yet choice seems inadequate to describe the series of events that led this genius to find himself neutered and dead-inside on his 50th birthday. And so he breaks out. Skyler is bewildered. She did not marry an empire builder, but a high school chemistry teacher. She is flustered. She considers his life — the lies, the late nights, the meth king-pinning — a breach of a faith and a danger to their family. He considers it the call of destiny. He transforms into what LBJ was his whole life. After all, LBJ too is in the empire business.

It’s tempting to see that as the defining difference between Skyler and Lady Bird and Jacqueline Kennedy. They hitched their ride to the rocket ship. Skyler had it thrust upon her. They bore what may. Skyler rejected it.

Breaking Bad fans’ disdain for Skyler is legendary, one of the exemplars of the (alleged!) Bad Fan phenomenon. No, Emily Nussbaum tut-tuts — Walt is an abuser! Skyler is protecting her family, negotiating an abusive domestic situation. Bad Fans don’t give a shit. They know war and death suck but they long for the atavistic call to crush your enemies, see them driven before you, and hear the lamentation of their women.

Note the specifics of this call: Walt may yearn for the lamentation of his enemy’s women, but he does not lust for them. Unlike LBJ and JFK, Walt is entirely sexless. Aside from Skyler’s infidelity and the cartel’s implied whoring in Mexico, the Breaking Bad universe is surprisingly sexless. Its aphrodisiac of choice is power. Walt ravages his wife as he rises from his metaphysical slumber, but otherwise he is maniacally focused on empire building. For LBJ and JFK women were fodder into their dreams, or at least delicacies along the way.

This atavistic call to men to rise above sexual temptation in favour of quest is ancient. Odysseus must resist the sirens’ song. Even more in tune with his heir in Walter White, he yearns for quest, for destiny, and is willing to answer its call at the expense of his family. As Dante writes in The Divine Comedy (John D. Sinclair's 1961 prose translation):

…not fondness for a son, nor duty to an aged father, nor the love I owed Penelope which should have gladdened her, could conquer within me the ardor I had to gain experience of the world and of the vices and the worth of men…

And as Harold Bloom expands in The Western Canon:

Dante bends toward the flame of Ulysses with desire, the longing for knowledge. The knowledge he receives is that of pure quest, made at the expense of son, wife, and father. The quest is, amid much else, a figuration for Dante's own pride and obduracy…

Quest at the expense of family, a figuration of pride and obduracy. Walt is our very own gnostic pre-Christian hero. Dante has Odysseus make this speech in hell, where he pays the price for his pride. So too does our hero Walt make the same descent.

We do not need to solve the Bad Fan dilemma for Breaking Bad (I think a case can be made either way).4 The truth is that fans are not weighing up her moral position. Their reaction is visceral. Fan contempt for her lies in their instinctive revulsion at domesticating nagging matriarchs. It cuts to the bone of the tension that underlies much of the epochal inter-gender dynamic around domestication. Fans do not want Skyler’s brand of bit and stirrup. The hearth of Lady Bird and Jaqueline Kennedy looks so much more enticing. Skyler may be right, she may have been wronged, but a man does not stand agog at her as he does when he reads about Lady Bird and Jaqueline Kennedy. And maybe this is deeply unfair. After all, it is precisely their suffering of endless torment and humiliation by their all-dominating husbands with poise and unflinching loyalty and love that makes them admirable. Men can only dream of such long leads.5

Lady Bird

So who is this God-tier wife? Why does Lady Bird command our affection and our admiration?

When LBJ was wooing his future wife he promised he would take her on exciting trips to see the museums she loved. After he married her, his tone changed, and those trips never eventuated.

Acquaintances who heard it were shocked. If he disapproved of the clothes his bride was wearing, he would tell her so, in a voice harsh with contempt, regardless of whether others were present. Across a crowded room—at a Texas State Society party, for example—he shouted orders at her, and the orders had to be instantly obeyed.

“Lady Bird, go get me another piece of pie.”

“I will, in just a minute, Lyndon.”

“Get me another piece of pie!”

Wingate Lucas says, “He’d embarrass her in public. Just yell at her across the room, tell her to do something. All the people from Texas felt very sorry for Lady Bird.” Seeing her shyness, her almost visible terror at having attention called to herself, acquaintances were soon making a remark that would be repeated for decades by acquaintances of the Johnsons: “I don’t know how she stands it.”

He dressed her down in public and compared her unfavourably to women in their entourage.

Also public were Lyndon’s constant attempts to get Lady Bird to improve her appearance, about which she had always been so sensitive—to make her lose weight, to wear brighter (and tighter, more figure-emphasizing) dresses, to replace the comfortable, low-heeled shoes she preferred with spike-heeled pumps, to get her hair done more often, to wear more lipstick and more makeup. And after 1940, when John Connally married Ida Nell Brill, Johnson was able to flick the lash even harder. The dazzling Nellie Connally was everything Lady Bird was not—perfectly dressed, outgoing, poised, charming, beautiful; as a freshman at the University of Texas, she had been named a Bluebonnet Belle, one of the ten most beautiful girls on the campus; as a junior, she was named the most beautiful: Sweetheart of the University. After Nellie became a member of the Johnson entourage, Lyndon made sure that Lady Bird never forgot the contrast now so conveniently near at hand, “That’s a pretty dress, Nellie. Why can’t you ever wear a dress like that, Bird? You look so muley, Bird. Why can’t you look more like Nellie?” Nellie, who had become close friends with Lady Bird, was distressed at such remarks.

When LBJ went off to war, he was forced to leave his congressional office to his wife’s management. She stepped up and nailed it. But LBJ did not let it last.

So impressed had Austin political and business leaders been with Mrs. Johnson that one day, Ed Clark recalls, when a group of them were at lunch, someone said, “kidding, you know,” “Maybe she’s going to decide that she likes that office, and then he’s going to wish he hadn’t gone off to war.” This joking became so widespread that it reached print in district newspapers; a letter to the Goldthwaite Eagle, for example, said that instead of re-electing Johnson to Congress in absentia, “I’d call a convention … and nominate Mrs. Lyndon Johnson for Congress to take her husband’s place while he is fighting for his country. She would make a good congressman.” The joking reached Johnson’s ears—and after he returned, he took pains to put it to rest, to make clear that his wife’s role as caretaker of his office while he was in the Pacific, and indeed her role in his overall political life, had never been significant. Once, in Austin, with a group of people present, he was asked if he discussed his political problems with Lady Bird. He replied that of course he did. “I talk everything over with her.” Then Lyndon Johnson paused. “Of course,” he said, “I talk my problems over with a lot of people. I have a nigger maid, and I talk my problems over with her, too.”

Later when the Johnson’s bought the KTBC radio station, which they made a fortune off as a channel for peddling political influence and gobbling up rivals they put political pressure on, Lady Bird shone as a manager of great ability:

And Mrs. Johnson was indeed an integral part of the business. David Benjamin, who had been a salesman for KTBC under the previous ownership and stayed on, was impressed with the speed with which Mrs. Johnson brought order to the previously chaotic activities of the station’s salesmen. “Mrs. Johnson knew who I had called on” and the results of the call, Benjamin says, “and she complimented me” or urged him on to greater efforts. Elizabeth Goldschmidt was not the only member of the Johnson circle who expressed admiration for Lady Bird’s diligence, energy and business acumen. Leonard Marks says (after emphasizing that “It was her station—don’t let anybody tell you to the contrary”), “Over the years, as the station prospered, I would go up to visit them at their home on Thirtieth Place on a Sunday.… She would have the reports of the week’s sales, the list of expenses, and we’d go over them. She could read a balance sheet the way a truck driver reads a road map.” In later years, moreover, Mrs. Johnson’s role in the station’s management greatly expanded, and her husband, in making major business decisions, began to rely more on her judgment, to a point at which Walter Jenkins, who was active in KTBC’s affairs, said, in words echoed by members of the Austin business community, “I believe he came to trust her judgment almost as much as his own.”

Heart attack

As a Senator, LBJ suffered a heart attack. Lady Bird stood by her man and more.

During those five weeks, Lady Bird Johnson left the hospital to go to her home—where, of course, there were an eleven-year-old and an eight-year-old daughter living—exactly twice.

She dressed to his taste and even lost weight in tandem with his post-heart-attack diet.

And as they grew closer, she tempered him. She calmed him. She restrained him. Maybe, in her small way, she even domesticated him. And he loved her for it.

TWO ASPECTS of Lyndon Johnson’s life changed during the six months he spent recovering from his heart attack.

One was his relationship with his wife.

He had asked her never to leave his bedside until he was out of danger, and she hadn’t left. “Every time I lifted my hand, she would be there,” he was to recall. After he left the hospital, Ruth Montgomery was to write, “Lyndon could scarcely bear to have Bird out of his sight.” On the ranch, Mary Rather says, “whatever Lyndon did, Lady Bird did with him. How she managed to run the house, attend to her children, talk to visitors and still take care of her husband, I sometimes wondered.” Chores that took her away from him were done while he was sleeping. Whenever he woke and asked, “Where’s Bird?” she “was always near enough at hand to answer for herself: ‘Here I am, darling.’” Their daughters, Ms. Montgomery was to write, “sensed a subtle change in their parents…. They seemed closer to each other than ever before.” “Of course, what happened, it deprived the girls even more of her presence and her motherhood,” George Reedy was to say.

And as Lyndon recovered on the ranch, Lady Bird was happy, happier than anyone could remember her being. “I never saw a woman more obviously in love with a man and more obviously grateful that he had been rescued,” George Reedy says. “In her face, you could see it. I remember once when we were walking down the path, she just reached over and gave him a quick hug. You could almost feel the joy bubbling in her veins that he was still alive. I think she forgot and forgave all the times that he’d made life miserable for her, which he did very often.”

And now, gradually, Lyndon Johnson’s treatment of Lady Bird began to change. Not that it became, by normal standards, considerate or even polite, but he began to allow her a role in his life, the life from which he had so largely excluded her ever since, in 1942, she had proven she could be effective in it. More and more, for other discussions—of issues and strategy—she was allowed to remain. So long as other politicians were in the room, she sat quietly, concealing her thoughts. After they had left, however, and she was alone with her husband and perhaps an assistant, he began to ask for her opinion, and Booth Mooney noticed that, more and more, when she gave it, “He listened to her.” He was particularly observant of her opinion on how a speech or issue would “play” to the general public. “Somebody else can have Madison Avenue. I’ll take Bird,” he was to say. He began to praise her publicly. During interviews with journalists, he would, more and more often, point to her picture on his office wall and, as Irwin Ross put it, “deliver some tribute to her wit or wisdom.” Even at home, although he still ordered her in the old bullying tone of the past, to run the most menial errands, more and more his orders to her would have at least a veneer of courtesy.

And in response, Lady Bird changed—in a change that was slow but sure and would eventually be so complete that it would amount to a transformation from the shy young woman who had once been terrified of speaking in public to the poised, dignified, gracious Lady Bird Johnson whom the American people were to come to admire in later years. “If ever a woman transformed herself—deliberately, knowingly, painstakingly—it was she,” Mooney was to say. “A modest, introspective girl gradually became a figure of steel cloaked in velvet. Both metal and fabric were genuine.” When she was seated on a dais, her face, while her husband was speaking, would still be tilted upward and toward him as unmovingly as ever, and her expression would be approving. But it was not long after their return to Washington in December, 1955, that she began, when her husband had been haranguing an audience for a long time, to slip him little notes as he stood speaking. And once, Mooney, picking up a note after a speech, read, with astonishment, the words she had written: “That’s enough.”

Then Mooney began to notice that the notes appeared to have an effect; sometimes, after receiving one and glancing at it, Johnson, about to launch into another area of discourse, would visibly check himself, thank the audience for its attention, and sit down. And once, when a Lady Bird note had had no effect, Mooney, from his vantage point on the dais, saw something even more astonishing: Lady Bird reached out, took the tail of Lyndon’s jacket, and tugged at it, and “soon afterward he stopped talking and sat down.” And there were other signs of the transformation. When, at cocktail parties, Johnson began pouring down Scotch and sodas at his old methodically intensifying rate, she would say a quiet word to him. Once Lyndon replied that “My doctor says Scotch keeps my arteries open.” “They don’t have to be that wide open,” she said with a smile.

Her encouragement and reassurance were constant and extravagant. Once, not seeing her at a public function, he demanded, with something of his old snarl, “Where’s Lady Bird?” and she replied, “Right behind you, darling. Where I’ve always been.” At a conference at which he became agitated, she slipped him a note. “Don’t let anybody upset you. You’ll do the right thing. You’re a good man.”

Lady Bird’s subjugation of herself to her husband was absolute. Their daughters are mentioned barely a few times across the span of the biography, and always as an afterthought to LBJ’s ambition.

“Anything that … needs to be done, remember this: my husband comes first, the girls second, and I will be satisfied with what’s left.”

And her support of her husband’s needs extended far indeed.

Lady Bird had, years before, at Longlea, learned to reconcile herself to this aspect of her husband’s behavior, and she hadn’t forgotten that lesson, as was proven during a conference among his physicians down at the ranch. Lady Bird was present, as was a single staff member, George Reedy, when the doctors again advised Johnson that he had to relax more, to do things he enjoyed, and Johnson told the doctors that “he enjoyed nothing but whiskey, sunshine and sex.” Reedy found the moment “poignant,” he was to recall. “Without realizing what he was doing, he had outlined succinctly the tragedy of his life. The only way he could get away from himself was sensation: sun, booze, sex.” It was “quite clear,” Reedy was to say, that Johnson was not talking merely about sex with his wife, and there was an “embarrassed silence.” It was broken by his wife, speaking to the doctors in a calm voice. “Well, I think Lyndon has described it to you very well,” she said. In later years, when more details of her husband’s sexual affairs emerged, she would sometimes be asked about them. She finally evolved a stock reply: “Lyndon loved people” she would say. “It would be unnatural for him to withhold love from half the people.” And the reply was always delivered with a smile.

The mistresses

I want to finish with a meditation on LBJ’s mistresses. His two principal mistresses, Alice Glass and Helen Douglas, are spectacular affairs, the same calibre of mistress as Lady Bird is of wife.

Alice Glass is a dazzling beauty with the majesty of a Viking and the enchanting charisma and endless legs of a water nymph. Even her name — a cut down, clear-cut, grownup transformation of the unreal Alice in Wonderland. A living fantasy.

Why was she drawn to the gangly Lyndon Johnson? The charisma of his will to power. Manifest most vividly in his endless gesticulating, it was the impression he could do anything, to mold the world to his will, that enchanted her.

And later Helen Douglas, one of the most beautiful and accomplished women in America. The drive that devoured in acolytes and shaped institutions and the wills of men also drew in her.

Alice Glass

Alice Glass was from a country town—sleepy Marlin, Texas—but she was never a country girl. She had been twenty years old when, six years before, she had come to Austin as secretary to her local legislator. Some smalltown girls brought to the capital as legislators’ secretaries became, in its wide-open atmosphere, their mistresses as well, but Alice Glass was not destined for a mere legislator. “Austin had never seen anything like her,” one recalls. She stood, graceful and slender, just a shade under six feet tall in her bare feet, and despite her height, her features were delicate, her creamy-white face dominated by big, sparkling blue eyes and framed in long hair. “It was blond, with a red overlay,” says Frank C. Oltorf, Brown & Root’s Washington lobbyist and a considerable connoisseur of women. “Usually it was long enough so that she could sit on it, and it shimmered and gleamed like nothing you ever saw.”

Bearing as well as beauty impressed. “There was something about the way she walked and sat that was elegant and aloof,” Oltorf says. “And with her height, and that creamy skin and that incredible hair, she looked like a Viking princess.” Legislators attracted to her at the roaring parties at the Driskill Hotel had sensed quickly that they had no chance with her—and they were right. Charles Marsh had lived in Austin then, in a colonnaded mansion on Enfield Road; at the Driskill parties, he held himself disdainfully aloof, as befitted a man who could make legislators or break them. On the same night in 1931 on which he met Alice Glass, they became lovers; within weeks, Marsh, forty-four, left his wife and children and took her East. He lavished jewels on her—not only a quarter-of-a-million-dollar necklace of perfect emeralds, but earrings of emeralds and diamonds and rubies. “The first time she came back to Marlin and walked down the street in her New York clothes and her jewels, women came running out of the shops to stare at her,” recalls her cousin, Alice, who was also from Marlin. And in Washington and New York, too, men—and women—stared at Alice Glass as they stared at her in Texas. “Sometimes when she walked into a restaurant,” says another man who knew her, “between those emeralds and her height and that red-gold hair, the place would go completely silent.”

And Longlea was her place. She had designed it, asking the architects to model it on the Sussex country home she had seen when Marsh had taken her to England, working with the architects herself for months to modify its design, softening the massiveness of the long stone structure, for example, by setting one wing at a slight angle away from the front, enlarging the windows because she loved sunlight, insisting that the house be faced entirely with the native Virginia beige fieldstone of which she could see outcroppings in the meadows below; told there were no longer stonemasons of sufficient skill to handle the detail work she wanted, she scoured small, isolated towns in the Blue Ridge Mountains until she found two elderly master masons, long retired, who agreed, for money and her smile, to take on one last job. She furnished it herself, with Monets and Renoirs and a forty-foot-long Aubusson rug that cost Marsh, even at Depression bargain prices, $75,000. And she had designed the life at Longlea, which was, because she loved the outdoors, an outdoor life. She organized a hunt—the Hazelmere Hunt, named after Longlea’s river, the Hazel—and even on weekends on which no hunt was held, horses were always ready in Longlea’s stable, and there would be morning gallops; as Alice took the fences (“The only thing Texas about Alice was her riding,” a friend says. “She could really ride!”), the little black derby she wore while riding would sometimes fall off, and the hair pinned beneath it would stream out behind her, a bright red-gold banner in the soft green Virginia hills. Warm afternoons would be spent around a pool (built, since Alice liked to swim in a natural setting and in clear, cold water, entirely out of native stone in a tree-shaded hollow); as Alice sat in her bathing suit with her hair, wet and glistening, falling behind her, her guests would try to keep from staring too obviously at her long, slender legs.

The focus of life at Longlea was not its magnificent interior but the terrace behind it. Breakfast would be served on that broad, long expanse of flagstone, as the morning sun slowly burned away the mist from the great meadow and the mountains behind it. In the evenings, after dinner, it was on the terrace that guests would sit, watching the mist form and the mountains turn purple in the twilight. Life at Longlea was as elegant as its designer. Champagne was her favorite drink, and champagne was served with breakfast—champagne breakfasts with that incredible view—and, always, with dessert at dinner, dinners under glittering chandeliers imported from France. Served by her favorite waiter: the most distinguished of the Stork Club’s headwaiters was a former Prussian cavalryman, Rudolf Kollinger; at Alice’s request, Marsh had hired him to be major domo at Longlea—even though, to entice Kollinger to private service, Marsh had had to hire as well not only his wife but his mistress. Witty herself, Alice loved brilliant talk, and at Longlea the conversation was as sparkling as the champagne, for she filled the house with politicians and intellectuals—Henry Wallace and Helen Fuller and Walter Lippmann—mixing Potomac and professors in a brilliant weekend salon. She had wanted to create her own world at Longlea—she had wanted a thousand acres, she said, because she “didn’t want any neighbors in hearing distance”—and she had succeeded. “Alice Glass was the most elegant woman I ever met,” says Oltorf. “And Longlea was the most elegant home I ever stayed in.” Arnold Genthe, the noted New York society photographer, who for years came regularly to Longlea, first as a guest and then to practice his profession—to spend day after day taking pictures of Alice because, he said, she was the “most beautiful woman” he had ever seen—asked that his ashes be buried at Longlea after he died because it was the “most beautiful place” he had ever seen.

*

ATTEMPTING TO ANALYZE why Alice was attracted to Lyndon Johnson, the best friend and the sister who were her two confidantes say that part of the attraction was “idealism”—the beliefs and selflessness which he expressed to her—and that part of the attraction was sexual. Marsh, Mary Louise says, was “much older” than Alice—he had turned fifty in 1937, when Alice was twenty-six—and, she says, “that was part of the problem. My sister liked men.” Moreover, they felt that Johnson, for all his physical awkwardness and social gaucheries, his outsized ears and nose, was a very attractive man, because of what Alice Hopkins calls that “very beautiful” white skin, because of his eyes, which were, she says, “very expressive,” because of his hands—demonstrating with her own hands how Johnson was always touching, hugging, patting, she says, “His hands were very loving”—and, most of all, because of the fierce, dynamic energy he exuded. “It was,” she concludes, “his animation that made him good-looking.” Whatever the combination of reasons, the attraction, they say, was deep. “Lyndon was the love of Alice’s life,” Mrs. Hopkins says. “My sister was mad for Lyndon—absolutely mad for him,” Mary Louise says.

*

THE PASSION eventually faded from Johnson’s relationship with Alice Glass. She married Charles Marsh, but quickly divorced him, and married several times thereafter. “She never got over Lyndon,” Alice Hopkins says. But the relationship itself survived; even when he was a Senator, Lyndon Johnson would still occasionally dismiss his chauffeur for the day and drive his huge limousine the ninety miles to Longlea; the friendship was ended only by the Vietnam War, which Alice considered one of history’s horrors. By 1967, she referred to Johnson, in a letter she wrote Oltorf, in bitter terms. And later she told friends that she had burned love letters that Johnson had written her—because she didn’t want her granddaughter to know she had ever been associated with the man responsible for Vietnam.

Helen Douglas

When Helen Gahagan Douglas was named one of “the twelve most beautiful women in America,” the critic Heywood Broun begged to disagree. “Helen Gahagan Douglas is ten of the twelve most beautiful women in America,” he wrote. At the age of twenty-two, the tall, blond Barnard College student with a long, athletic stride became an overnight sensation in the Broadway hit Dreams for Sale, and she was to star in a succession of hit shows, marrying one of her leading men, Melvyn Douglas. Deciding to study voice, she made her debut in the title role of To sea in Prague, and toured Europe in operas and concerts for two years, before returning to more Broadway starring roles and radio appearances. On screen, she played the cruel, sensual Empress of Kor in the film version of H. Rider Haggard’s novel She. By 1936, the New York Herald Tribune noted that “Helen Gahagan Douglas has made her name in four branches of the arts—theatre, opera, motion pictures, and radio.”

Driving across country with Douglas after their marriage, Helen had been touched by the plight of Okies trekking west, and plunged into a new field—politics—with her usual success. She became Democratic national committeewoman from California, and in 1944, at the age of forty-three, ran for Congress from a Los Angeles district, and won, becoming one of nine women members of the House of Representatives. Washington, one journalist wrote, “had prepared for her tall, stately and gracious beauty, but they weren’t prepared for her brilliance, in short, her brains.” A friend of Eleanor Roosevelt’s (whose husband, Helen said, was “the greatest man in the world”), she was a frequent guest at the White House, while Melvyn remained back in Hollywood making movies. On the House floor she was a striking figure, generally “surrounded,” as one account noted, “by attentive male colleagues,” and she was a riveting, charismatic speaker in her advocacy of liberal causes, particularly civil rights. Declaring that “she stood by the Negro people when they needed a sentinel on the wall,” Mary McLeod Bethune called her “the voice of American democracy.” She won re-election in 1946, and again in 1948, and was one of the most sought-after speakers for liberal rallies across the country. And in an era in which age supposedly dimmed a woman’s charms, hers seemed as bright as ever. A profile in the New York Post in 1949 commented that during her years in Congress “her waistline has grown even slimmer, her face leaner.” In her speech at the Democratic National Convention in Philadelphia the previous year, the Post said, “she boosted her stock still higher by turning out to be gorgeous on television.” The New York Daily News called her the “Number One glamour girl of the Democratic Party.” It was widely expected that she would run for the Senate from California in 1950, and would win.

SHE HAD FIRST MET LYNDON JOHNSON in 1945 when, shortly after she arrived in Congress, he dropped around to her office, “draped his long frame in one of my easy chairs,” and asked how things were going. When she said that she was having trouble organizing her office, he said, “Well, come up and see how my office is run.” She found his office “very impressive. It worked. If he wanted something, it came within a half second.” There were “other industrious offices,” she was to recall, “but the efficiency of this office and the extent that they went to reach … the lives of his constituents in an intimate way was something that utterly fascinated me.”

She was impressed as well by qualities which she discerned, with a very penetrating eye, in his character: by his instinct for power; by his ambition; and by the method by which he concealed views that might stand in the way of the realization of that ambition—a method that, she felt, required great strength.

And, she felt, she knew where Johnson really stood: she was sure he was a New Dealer like her. “He cared about people; was never callous, never indifferent to suffering…. There was a warmth about the man.” That was why, she says, that “despite some of his votes, the liberals whom he always scoffed at … nevertheless forgave him when they wouldn’t forgive someone else.” While his attempt to portray himself as an insider offended some of his House colleagues, it didn’t offend her. “He knew what was going to happen…. [he] exuded the unmistakable air of the keeper of the keys.”

I quote from all four volumes without specifying which volume I am quoting from. Occasionally I trim quotes for the sake of brevity.

There is a piece to be written about the way LBJ made his men achieve the impossible, the way he rapidly assembled the best team for a job and got things done. It’s a story fit for the best entrepreneurs and highest performing teams today.

This may well be our own projection, not Walt’s grief. He only shows signs of love for his wife. It’s not obvious to him she is complicit in his malaise. And she may not be. His relationship with her is a symptom not a cause of it.

The case for Skyler is easily made: she was right. Walt’s unleashed ego destroyed his family, got his brother-in-law killed, made him reviled by his son and wife. She is a caring wife: she cared deeply for him when he was going through his cancer scare. She’s a good mum.

The case against: Walt was basically right throughout, and he ultimately did make a bucket-load of cash for his family to live off at the expense of his death (which drove his critics nuts).

One framing of the cases: American Protestantism against a kind of atavistic universal tribalism. The WEIRD Protestant ethic tut-tutting at Walt’s bad behaviour, the atavistic universal tribalism urging him forward to conquer and demanding his clan (and woman) stand by him. But that’s an argument for another time.

This is not that surprising when you consider that even a man like Stalin can look sympathetic beside an oppressive wife. Here is Stalin, cowering behind a bathroom door in Simon Sebag Montefiore’s Stalin: The Court of the Red Tsar:

Stalin confided in Khrushchev that he sometimes locked himself in the bathroom, while she beat on the door, shouting.

'You're an impossible man. It's impossible to live with you!' This image of Stalin as the powerless henpecked husband besieged, cowering in his own bathroom by the wild-eyed Nadya, must rank as the most incongruous vision of the Man of Steel in his entire career. Himself frantic, with his mission in jeopardy, Stalin was baffled by Nadya's mania. She told a friend that 'everything bored her - she was sick of everything'.

I regret to inform you that this reader’s sympathy does not lie here with Stalin’s deranged wife (who ultimately killed herself from this madness).

Hi Misha,

it seems to me one of the questions you explore in your writing is how to be a man in the world of today. Like me, you seem to have a longing for a simpler past. Your writing about the Green Book, the Conquistadores, about the way boys of the Plains Indians were raised and when grown up lived as warriors, your retelling of the lives of JFK, LBJ and Coke Stevenson, in my mind are all examples of this. They refer to a time when it was easier to live out the innate desires of men to conquer, have sex with many women, and to use violence without inhibition. Not that I want this, but how to reconcile these urges with life in the world of today? I feel domesticated and I don't like it.

Anyway, this is one of the things I resonate with in your writing.

Again, I want to promote a piece of mine (which takes only one minute to read), since it is about an aspect of manhood, although on a very different level. Curious to know what you think of it. Also, comments about style and word choice are greatly appreciated, since English is not my mother tongue.

https://henkb.substack.com/p/the-advantages-of-sitting

Okay, TL;DR: Yes we love to see powerful men do impressive feats, and it's cool to be a loyal spouse, all else being equal. But loyalty to very-bad-behaving spouses is contemptable. True, it's annoying as a TV viewer to see our antihero's galivanting be hindered, but Skyler is reasonable and admirable mostly and the haters are wrong! :)

The long of it: I assume you're being ironic about the God-tierdom of Ladybird and Jackie, else I think you're way too glib about the casual cruelties done by their husbands and the nobility of the wives enduring it. I think this is why you're wrong about Skyler too and that she's a better person and wife than early Ladybird at least.

The Skyler haters are wrong and the orthodox view (the writers' view) that she's right/reasonable is the correct one. Will get to Breaking Bad in a bit though.... First:

I respect Jackie's loyalty to and love of JFK despite his philandering (though I don't like his infidelity) as JFK had many virtues and didn't bully or humiliate her otherwise, AFAIK. As for Ladybird, I can admire her efforts and role she carved out post-heart LBJ's attack. But before then? It sounds like LBJ treated her horribly and it's hard for me to see her subservience to a persistent bully as a model marriage nor model wife.

I've not read Caro so won't press the point too much on LBJ but I'm not an admirer from what I know of his policies and behaviour.

Okay, to Breaking Bad! And further to our previous Twitter exchange (https://twitter.com/Alex__H13/status/1645930680218525696 ) :

Where I agree:

1. ' He can buy weed if he wants to, he’s a grown-ass man.' - Indeed. And clearly the relationship is lopsided in the pilot episode and Walt is babied by Skyler. this is bad. It'd be better if Skyler could really see through Walt's fake smiles. But he's babied because he allows it. No assertiveness.

2. 'Yet her soul is slowly crushed as Walt’s ascends. Their roles flip. Whereas he had been a

subservient husband imprisoned in her suburban prison, she is now subordinated to his will, his thirst for power and empire building.'

Agreed, with this caveat: neither are truly imprisoned by one another. They choose to stay in a suboptimal situation as defecting is costly for both. I sympathise with their misery, but it is on them as they each refuse to solve it: Skyler by divorcing him and turning him in in early s3, and Walt by growing some balls before s1 ep1, getting a better job and asserting himself at home!

3. 'The truth is that fans are not weighing up her moral position. Their reaction is visceral. ' - Yeah, regrettably! I'm with Bryan Caplan that most voters are wrong. So it is with Skyler haters. Their visceral reaction is WRONNNNNNG. Skyler annoyance by fans would be understandable, esp in s1 when our hero/antihero is being hindered and he's not fallen too far morally. What's less cool is the hate, esp as Walt strays further to evil. There's a strong whiff of sexism, as you note:

'Fan contempt for her lies in their instinctive revulsion at domesticating nagging matriarchs. It cuts to the bone of the tension that underlies much of the epochal inter-gender

dynamic around domestication. Fans do not want Skyler’s brand of bit and stirrup. '

Where I disagree:

1. 'No, he doesn’t owe her.' (re his staying out late "buying weed" and not explaining anything to her about his erratic post-diagnosis behaviour he's yet to reveal to her).

WRONGGGGGG. He's a bad husband and this is the start of his persistent lies to her. Which she's admirably wise too from the get go and calls him on it!!

2. 'As the pressure mounts, what does Skyler do? She leaves Walt. She takes the kids. She sleeps with her boss. She takes Walt’s cash and pays off her boss’s tax debts.'

She separates from Walt but this isn't really or mainly about the meth. It's because he lied to her and did crazy things persistently (e.g. fugue state). She's much better inclined to him when he's a more honest crook from s3 and before the s3 finale when the real dangerous with Gus stuff kicks in.

She fucks Ted as a counter strike to Walt refusing to leave the house (again after his persistent bad behaviour) . And she pays Ted off as he's a threat to Walt's interests as well as her own: e.g. IRS will look at her hard and so see Walt's illicit money in the car wash laundering op. That is God-tier, proactive spousery!

Skyler's anti Walt the most when danger looms to the kids: e.g. after these moments: "I am the danger" scene where Walt snarls at her when discussing Gale getting shot in the face; Walt freaking out and screaming in the crawl space about men coming to kill them in s4; after Walt blows up Gus & 3 others while Skyler is hunkering down at Hank and Marie's protected by DEA armed teams; when Walt tells her glibly in s5 that Jesse held a gun to his forehead.

Come on! Her behaviour in wanting the kids away is laudable and reasonable. You concede she's a great book keeper. She also never rats Walt out till he asks her to. She covers for him for a long time (very competently). He allows her credit for the laundering but keeps her away from the meth business despite her being competent/trustworthy enough to know the truth and having an interest in knowing the real risks that he hides from her.

3. 'by the end of the first season he’s ravaging her in the living room and the car. And she hates it.'

Not true. She's really into Walt's first ravaging at end of ep1 and is very much into the car sex. She's beaming as she tells Walt's cancer doctor about his new libido. She does strongly reject him when he forces himself on her in ep1 of season 2 though (very reasonably- she says let me get the face mask off of my face first!): https://youtu.be/5tbaDMYzPyo

4. 'We loathe Skyler'.

I don't loathe her and I think loathing is a minority view, though perhaps is a significant plurality of the hardcore fans.

I get why people are annoyed by Skyler's chiding of Walt's antics in in s1 & 2. I share that annoyance and think it's creator intended. We want Walt to Break Bad and Skyler makes it trickier for him to do it . Skyler is completely reasonable in her reaction to Walt's behaviour though as per above paras.

I think my unease with your post's thrust is summed up by Tom Holland in Dominion (me paraphrasing Holland):

I was fascinated as a child by the ancient Romans, Persians and Greeks for the same reason I loved dinosaurs like the T-rex: they were the apex predators of their worlds. I disregarded the wimpy, desiccated Christian world that followed. Only to later find I shared little with ancient Greek, Roman, Persian values and that I owed my values to Christianity. The former were murderers, ace torturers, rapists, pederasts. The latter overthrew them and made our liberal world.

Me again: I see the LBJs and Walter Whites as the T-rex or Romans. Awesome in their power., loathsome in their values/actions. They're great to read/watch but not to encounter in reality.

Sure the Christianly worrying of Skyler can be annoying but the haters underrate her not being at ease with lies and violence. Skyler was a great wife (loyal, loving) to the extent she could be given her circs. If she'd not pushed back at Walt's endless lies and moral downward spiral and gone along easily, we'd be right to really loathe her.