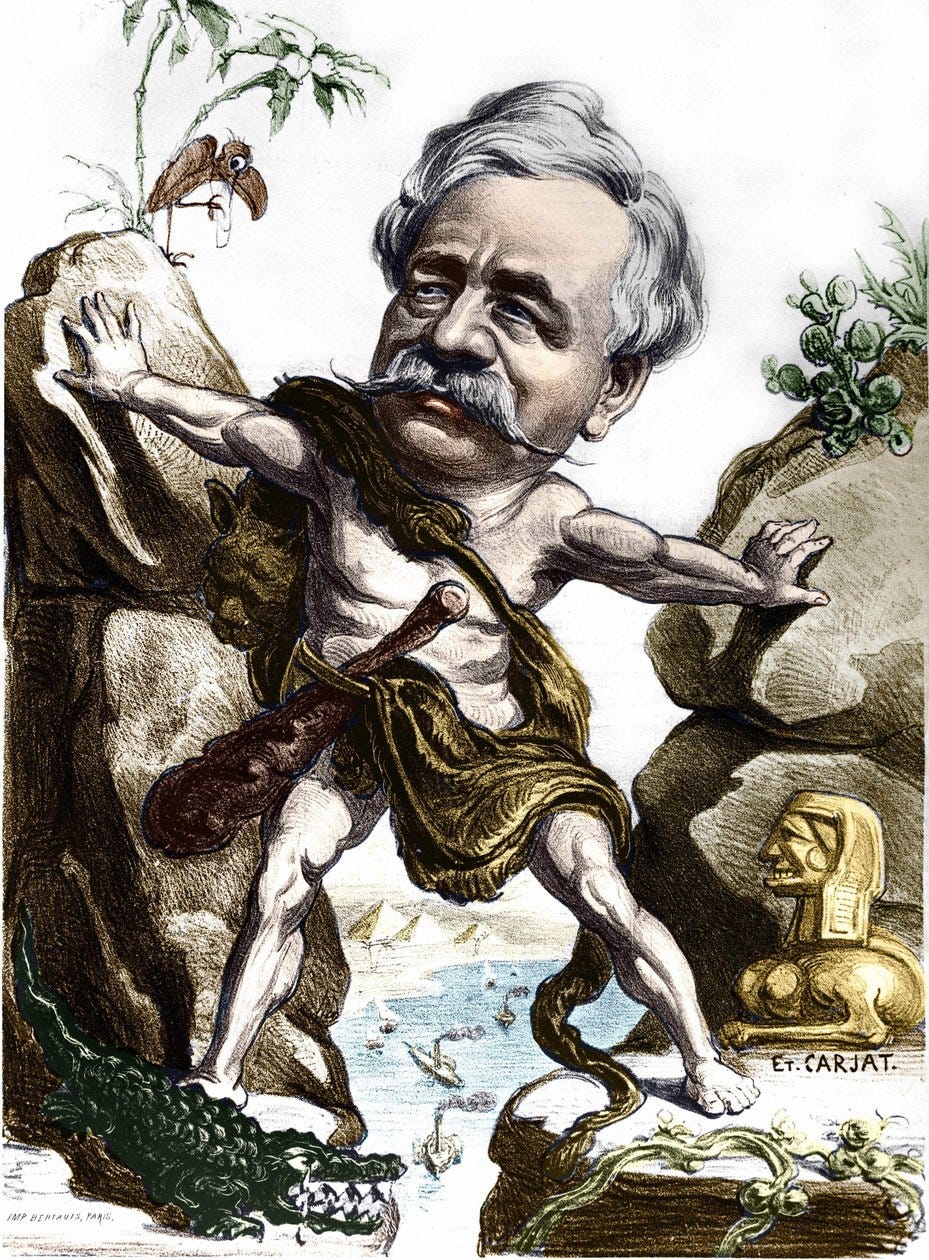

The Miracle Man of Suez

The genius of will that cut a continent in half

Unless otherwise attributed, quotes are from David McCullough’s The Path between the Seas: The Creation of the Panama Canal, 1870-1914.

It began with a combination of forces that would, a century later, seem strikingly familiar: the vast wealth of Middle Eastern potentates, the fanatical devotion of a retail investor base, and, at the center of it all, a man possessed of an indefatigable, almost pathological will. It was a saga of disruption on a planetary scale, driven by a figure who treated reality as something to be negotiated rather than obeyed. Not Elon Musk, this was Ferdinand de Lesseps, and the world he intended to disrupt was the very spine of the earth: the Isthmus of Suez.

De Lesseps came from a family that treated the impossible as a kind of inheritance. His uncle Barthélemy had sailed with La Pérouse around Cape Horn to Kamchatka, then had crossed the whole of Siberia by dog sled alone in winter to present himself to Louis XVI at Versailles dressed as a Kamchatkan. He was a national hero overnight. His subsequent career survived imprisonment in Turkey and the retreat of Napoleon’s Grande Armée from Moscow. Ferdinand grew up nourished on these tales of heroic triumphs. By the time he entered the French consular service and was posted to Egypt, he had been soaked in ambition and self-belief.

De Lesseps' opportunity came in the form of a friend, Mohammed Said. To understand Said the man, one must first understand the boy. He was a creature of pathetic isolation, a “fat, unattractive, and friendless” child, sequestered within the gilded cages of the Egyptian court of Mehemet Ali. In that court, weight was a sign of lethargy, and the young prince was forced into brutal regimens of exercise to curb his girth. But there was one man who offered the kindness the boy’s own father withheld: de Lesseps, then a young French vice-consul. De Lesseps provided the companionship and even the secret snacks a lonely prince craved.

By 1854, the boy had become the Viceroy. He was no longer a trembling child but a “walleyed mountain of a man,” a gargantuan figure who consumed life with a terrifying intensity. He was a ruler of whims and fire, a man who amused himself by forcing his pashas to carry lighted candles through chambers of gunpowder as a test of nerve. De Lesseps knew the moment had come. He travelled to Egypt, bringing his own mahogany furniture, his quilted silk, and his very own ice to chill the desert heat.

On the morning of November 13, at a desert command post outside Alexandria, the two men met. The air was thick with the scent of ten thousand soldiers and the dust of Bedouin cavalry. Said was in top spirits, eager to mark his reign with a monument that would outlast him. He asked for an idea. De Lesseps waited for a sign. And then, in the cold predawn of the following morning, as he stood before his tent wrapped in a red dressing gown like some ancient patriarch, he saw it: a rainbow, vivid and searing, arcing across the sky from the darkness of the West to the light of the East. It was a “token of a covenant”, De Lesseps wrote in his diary.

Before the assembled generals, he mounted his horse and leapt over a high wall — a bit of imprudence that was, in fact, a calculated stroke of political genius. To the pashas, a man who could ride like that was a man who could be trusted. By sunset, the Suez Canal — a dream that had defeated pharaohs—was settled. No one asked how much it would cost.

If the birth of the project was a matter of desert rainbows and galloping horses, its realisation was a brutal, fifteen-year odyssey of sheer, unadulterated will. De Lesseps was not an engineer; he was not a financier; he was a man who possessed what Jules Verne would later call the “genius of will.” He fought against the British Empire and the geography of the planet itself. For ninety-nine miles, the desert stood as a barricade of prehistoric clay and shifting silt between the Mediterranean and the Red Sea — the only obstacle between Europe and Asia that wasn't a months-long voyage around the Cape of Africa. There was no water. To even begin the work, de Lesseps had to first conjure a freshwater canal out of the Nile, a gargantuan preliminary task involving thousands of laborers just to keep the army of excavators from dying of thirst in the heat.

In the north, at Port Said, there was no natural harbour, only a shallow, treacherous shoreline. De Lesseps’ engineers had to invent a way to manufacture stone where none existed, casting 25,000 enormous blocks of artificial concrete — each weighing twenty-two tons — and plunging them into the Mediterranean to create a two-mile breakwater. In the center of the Isthmus lay the Serapeum, a massive plateau of hard, compacted sand and rock that rose like a wall against the Mediterranean’s progress.

Whole stretches of freshly dredged canal would refill overnight, erased by wind-driven sand that poured back into the cuts. Crews of Egyptian fellahin returned at dawn to find days of labour undone. In the summer of 1865, cholera swept the camps so fast that there were not enough workers left standing to carry the dead for burial in the desert. Estimates of the total killed across the decade range from twenty thousand to over a hundred thousand; the Suez Canal Company kept no reliable count. Men were plentiful, and Egypt seemed inexhaustible.

When the British, desperate to sabotage the project, successfully pressured the Sultan to abolish the corvée — the system of forced Egyptian labor — the project teetered on the brink of collapse. Thousands of men vanished from the pits overnight. De Lesseps pivoted. If men were taken from him, he would build machines. He oversaw the deployment of a new kind of industrial army: colossal, custom-built steam dredges and long-chambered elevators that could lift 2,000 cubic meters of earth in a single day. These were the monsters of the nineteenth century, mechanical titans that groaned and hissed as they clawed the canal out of the desert floor, moving a total of 75 million cubic meters of earth — enough to build a wall around the entire coast of France.

This mechanical miracle was fueled by a different kind of power: the savings of the French people. When the smart money of the London and Parisian banks turned their backs, de Lesseps went to the public. He bypassed the institutions and spoke directly to the small shopkeepers, the country priests, the retired soldiers. He sold them not just stock, but a share in a national crusade. These twenty-five thousand small investors provided an initial 200 million francs, creating a base of stakeholders whose loyalty was to the man. When the Rothschilds wanted 5% for handling the subscription, he told them he would hire an office and do it himself.

For fifteen years, de Lesseps was everywhere at once — Egypt, London, Constantinople, Paris — coaxing and flattering. He faced the scorn of the English Prime Minister Lord Palmerston, who called him a swindler and a fool. He faced the technical dismissal of Robert Stephenson, builder of the Britannia Bridge, who pronounced the scheme preposterous from the floor of Parliament. De Lesseps, whose English was terrible, responded by hanging a French flag from his hotel window on Piccadilly and giving eighty speeches in a single month across the British Isles. “They never achieve anything who do not believe in success,” he said.

The cost was astronomical. By the time it was finished, the project had nearly put Egypt into bankruptcy. Mohammed Said had died, replaced by Khedive Ismail, who was even more beneficent and even more reckless. De Lesseps claimed he had no interest in making money. “I am going to accomplish something without expediency, without personal gain,” he once wrote. At any time he could have sold his precious concession and realised a fortune, but he never did; his driving ambition was the canal itself, “pour le bien de l’humanité.”

November 17, 1869, was the day of his transfiguration. Ismailia was a mirage made flesh — a town conjured from the sand, complete with hotels, palaces, and a town square where six thousand guests from across the globe gathered. The Khedive had spared no expense. He built a Cairo opera house and commissioned Verdi to write Aïda. He imported five hundred cooks and a thousand waiters from Europe. On the deck of the imperial yacht, Aigle, de Lesseps stood beside his cousin, the Empress Eugénie. Behind them steamed the Emperor of Austria, British ironclads, and Russian sloops — fifty ships in all, moving through the desert under a “dreamlike resplendence,” Eugénie remembered.

For the next eight months, until the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War, he was Europe’s reigning hero. The Empress presented the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor. The Emperor hailed his genius. And in a final flourish of his irrepressible vitality, in celebration of his great victory, at the age of sixty-four, de Lesseps married a stunning French girl of twenty who would bear him twelve children.

Few men had ever been so vindicated while they lived. Lord Palmerston was in his grave, and the new British Prime Minister, Gladstone, was forced to bestow upon de Lesseps the Grand Cross of the Star of India. He had become a new thing under the sun — the entrepreneur extraordinaire. He possessed the genius of will, a stubbornness so absolute it bordered on the divine. He had outworked the engineers, outmaneuvered the diplomats, and outlasted his enemies, proving that in the theater of history, a single man's will, backed by the gold of princes and the faith of the common man, can reshape the very surface of the earth.

What no one yet understood — least of all de Lesseps himself — was that the same faith, applied to a different geography, would soon bury twenty thousand men in the jungle and drown the savings of a nation in the mud.

Exceptional writing 👏!

Magnificent. We still benefit from the great canal and are so grateful for his vision and energy. Masterful description of a Great Man