Atlanta

Black agency and the grim sheen to black whimsy in Atlanta

As nearly as any honky could, he took into account her problems with her prostitute daughter, her jailed criminal son, and with the other son whose HIV troubles and scrambled wives and children were too complicated to describe. On quiet afternoons he, Ravelstein, would sometimes listen, sympathetic, half dreaming, to Ruby Tyson’s stories—really beyond his reach or interests. The old woman presented herself as quiet, dignified, and sadly reserved. You can imagine how Ravelstein would have listened; the chaos the life of such people must be.

— Saul Bellow, Ravelstein

To Abe Ravelstein in Saul Bellow’s novel, the intricate gutter-lives of his elderly black maid’s relatives are incomprehensible — they’re “beyond his reach or interests”.

Atlanta has the opposite effect: it renders the thug-soaked lives of Atlanta blacks legible and interesting — and even relatable.

We can smell the weed-haze and feel the greasy post-munchy skin and hangover thud — but we like the protagonists Earn, Van, Al (aka Paper Boi), and Darius. Imperfect, but mainly earnest and trying to make their way in the world, we keenly follow these black amigos and their quirky human stories that occasionally warp and spasm into the absurd and otherworldly.

Re-watching Atlanta, I forgot how good it is. Like, really good. One of the best TV shows out there (speaking only for seasons 1 and 2 so far…1). It has to be up there with Coming to America as one of the great cinematic experiences by and about blackness, transcending its subject in the same way Philip Roth’s or Woody Allen’s or Larry David’s Jewish corpuses transcend the Jews. Like Jerry Seinfeld, Donald Glover is a weak actor, but also like Jerry Seinfeld, his crew and his writing make it work. Funny, sad, touching in the whimsical way of Fleabag or Mr Inbetween. Self-lacerating in the way of Girls; we like and go along with the protagonists, even when they and their worlds are condemned.

Magic realism meets grim black life in Atlanta. The hardships of poverty permeate everything. Everyone you meet is a hoodlum, a trickster, or a thief. At best they’ll gnaw your ear off with some hustle, at worst a gun to the head. Life for Atlanta blacks is about survival. Surviving school, surviving life. Maybe if you’re smart you can escape the slaughterhouse but your default destiny is prison or death.

“I like Flo Rida. Mom's need rap too”

— Darius

Interactions with whites are jarring in different ways — sometimes just soaked in mutual misapprehension and the endless comedic riff in the space between a black tough and a white twink office worker, but often enough in black-on-white crime. Whites are never friends. They’re strange distant creatures, like autistic elves or twinks. Harmless, goofy apparitions (except one prison officer early on who beats a mentally ill prisoner). Violence always lingers on the edges, bleeding in unexpectedly. When white racism is real enough, it’s hard to even get that riled up, boxed in as it is by actually criminal blacks. When a big black thug is refused a job and calls his dapper white interviewer racist, we don’t feel bad for him: he’s fresh off a robbery. If the interviewer judged this book by its cover, he judged right. When Earn stands out in a German festival, refusing to dress up and join in, we feel for him — we know that guy, we’ve probably been him sometimes. And yet he’s the jerk. His pretty black kinda-girlfriend fits in just fine. These German goofballs aren’t anti-black, Earn just doesn’t fit in. When Al’s latest girl complains about competing with lip-filler whites on Instagram, she abuses her Asian pedicurists in the next breath. An obnoxious, loud former stripper, she cackles at Al: “you could have been just another dumb broke ass nigga” at that strip club for all she knew. Reality in Atlanta is textured, messy. Real.

Whenever Atlanta plays with racism it ends up mocking the idea itself: the weird southern frat boys with the confederate flag end up being extremely hospitable to the guys, and it’s our black amigos who end up stealing from them. Paper Boi wants a Jewish lawyer — not a black one — so he ain’t robbed by no Don King (to paraphrase). When they go to a Haredi passport office, everything works. Primo pricing for primo service. Earn asks the Haredi operator, desperately seeking answers to secrets buried somewhere in the universe out of reach: do you know any black lawyers as good as your Jewish cousin? Why, he seems to beg, why?? We get the sense that Harry Potter may as well ask a Gringotts goblin if a muggle banker would do. The Jew panders to him, muttering something about of course there are black lawyers just as good, but his cousin’s got the networks for systematic reasons. The secret remains buried, out of reach.

You should do what we do,

stack chips like Hebrews.

— It’s All About the Benjamins, Diddy

Holla at my Jewish lawyer

To enjoy the fruit of lettin’ my cash stack.

— Jay Z, No Hook

But racism is the least of their issues. Each episode is an odyssey through black dysfunction. Broken homes, robbery, joblessness, unreliable friends and services. There is not a single positive father figure in the show. Nor is there a positive maternal figure, come to think of it, but the show really relishes in its lack of father figures, stretching the joke to build a monument to paternal dysfunction. The main father figure is a manakin ode to an abusive father in the crackpot home of a Michael Jackson-esque psycho:

"I want this wing of the museum to be dedicated to great fathers. My father, Joe Jackson, Marvin Gaye Sr., Tiger Woods's father, Serena Williams's father, the father who dropped off Emilio Estevez in The Breakfast Club."

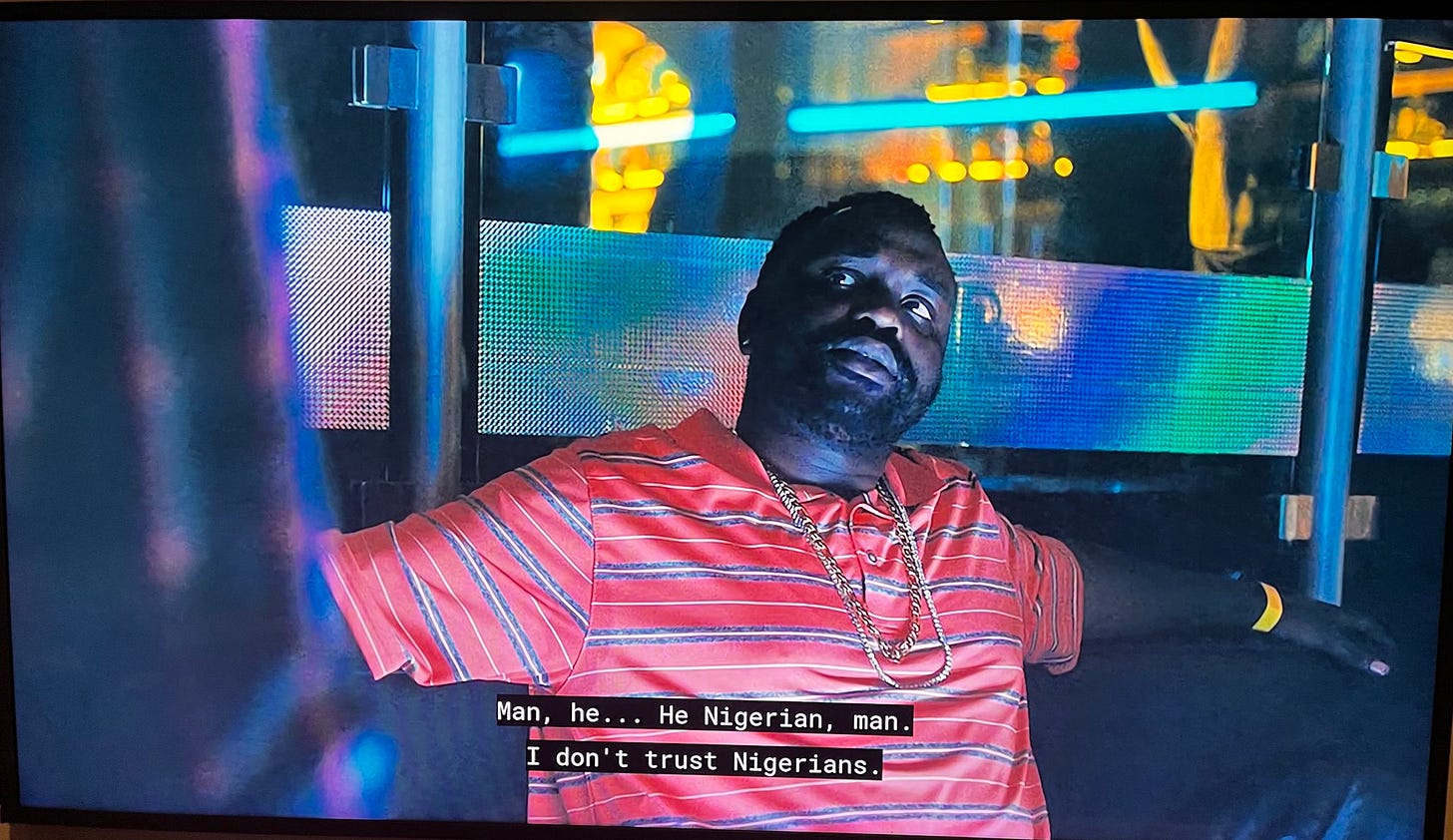

Our protagonists, as sympathetic and put upon as they are, are also derelicts, drop kicks, or thugs. The show opens with them shooting someone and being remanded in prison. Everyone in the show is cursed. Poor criminal degenerate blacks, black-sycophantic whites, white-wannabe blacks, belligerent racist whites, upwardly mobile sellout blacks, ridiculous black talkshow hosts, ridiculous black ads. Black women are strippers or single mums or some species of escort. No one’s left with clean hands in a meagre dog-eat-dog world of rascals and eccentrics barely getting by. Only Darius is pure, an affable source of strange wisdom and an otherworldly cadence, whose only fault is he’s Nigerian.

Whilst the show’s exposition of blackness is rich and raw and often bleak, in the end its stance is of course affectionate. Which makes the profound dysfunction it portrays all the more poignant. This is the morass fundamentally good people and aspirational blacks must grind through. To our protagonists, the derangements of black life are not normal, they are as confronting to them as it is to us. And amidst the invisible cars and murder-suicidal Michael Jackson freaks are real anxieties about love and parenthood and commitment and family and friendship and sex.

“Bitch how old are you? Still using condoms? What are you in high school?”

— Van

The show is pre-woke in its politics, or lack thereof. It ribs its own. No one is pure. An early prison scene is sublime. Everything is deranged, all are cursed. The prisoners are guilty and mentally ill. The guards are indifferent and violent. “Sexuality is a spectrum, you can do whatever you want,” our boy Earn assures an inmate getting ribbed for dating his ‘girl’ (a transsexual — “my nigga, that’s a man,” says an inmate). “No, bad boy gay,” chimes in someone from the laughing crowd.

"I would say it’s nice to meet you but I don’t believe in time as a concept so I’m just going to say we always met."

— Darius

Atlanta is too smart, too creative, too original, too real to be political. But if it were it’d be reactionary in its portrait of blacks trying to make their way in the world, flailing, but self determined. The blacks in Atlanta have agency. The show is never really tempted to blame someone else. Some are good, some are bad, some are competent, most are useless. Where The Wire is grim and gritty and conniving, Atlanta is whimsical and absurd. At the edges of its world growls a constant danger, the desperation of poverty, an accumulated unfairness that gums up every move. But through that haze each man and woman has agency and each are responsible. Uncle Willy the Alligator Man is an embarrassment, a failure who squandered his potential. He is ashamed because he was the smart one, he could have made something of himself but he didn’t and there is no one else to blame but himself.

In another episode, a black woman confronts a pretty white girl for dating a famous black. “I’m tired of that story,” she tells her. “Maybe I’m just a good woman,” the pretty white responds. She was with him from when he was a nobody theatre kid. They love each other. The black woman is rude and dismissive. She don’t have no time to wait around for some broke ass theatre kid. Atlanta shivs its own blacks, even when it feels for them. And keeps shivving them: “We’re all here just trying to have a good time. Black people. Non violent,” pleads Earn right before his black pal knocks out a black assailant.

Every run-in is fraught with peril. Your fans will rob you on the street. Even your dealer will rob you. Your barber will take you on an odyssey through his broken family. The land of the blacks is beset on all sides by darkness. The land of the whites is absurd in its sheen, far off on a distant hill, impregnable to most blacks. Atlanta doesn’t scold whites for this state of the world, as the current zeitgeist might. Atlanta blacks have agency. But it stews in its despair, manifested in endless absurdity. Even the strange black sage, the apparition, the devil that appears to Paper Boi in the woods after he’s set upon by fans-cum-hoodlums sticks a knife to his throat. In black lives even their dreams rob them. The black devil tells him to make a decision or he’ll cut him. Agency is what matters.

Episode 1 of season 3 is disappointing (murderous white hippy lesbian foster parents? Yeah right).

Regarding the footnote, Season 3 Episode 1 is clumsy but based on a true story!

https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hart_family_murders

Love this show. And I liked that episode. Strong Mia Farrow energy...

Glover appears for a minute on Girls and I can't help thinking he noticed pocketed the right things. He's not a great actor but he is a great mimic.