Australia: Sub-Imperial Power

Wisdom and delusion Down Under

Australia is not a victim of this imperial order but a junior partner and enthusiastic — if anxious — supporter. It is not anxious because the imperial system involves frequent warfare but because it fears that the imperial centre is not sufficiently attentive to Australia.

Everyone is polite enough not to mention that it took twenty years, trillions of dollars, six Australian Prime Ministers and four US presidents to replace the Taliban… with the Taliban.

— Clinton Fernandes, Sub-Imperial Power

I have never read a book where I’ve penciled in as many hard-etched underlines in agreement at the same time as literal ‘lol’s in the margins.

Let’s begin with the furious nodding and consider the book’s glaring defects later. Sub-Imperial Power: Australia in the International Arena by Clinton Fernandes nails its core thesis: Australia’s foreign policy is best understood as an appendage to US power in the age of Pax Americana. This role it played for the British since its inception as a British colony.

Fernandes claims:

Australia is a sub-imperial power upholding a US-led imperial order. This means the US effectively controls political sovereignty over Australia. Australia is not an exploited colony, but rather a regional lieutenant.

The ‘rules-based international order’ is not an inclusive order created for the benefit of humanity. It is power politics by procedural means. This order was born in the wake of WWII, with institutions like the UN created to entrench US world leadership to “amplify rather than constrain US power abroad and help manage American public opinion of its global role”. (On a deeper history of this I recommend Tomorrow, the World: The Birth of US Global Supremacy by Stephen Wertheim.)

Australian defense and foreign policy operates under a regime of secrecy, often behind the cover of expertise. In fact, no special expertise is required to understand or to judge it and the reason for secrecy is to allow the Australian polity to effect its role as US sub-imperial power rather than risk exposing it to democratic input. (We might take this critique further: most (all?) subjects can be understood by a smart and interested layman and the ‘secret knowledge’ of experts is generally overrated. Nothing is beyond your ken!)

Henry Kissinger: an expert is someone skilled in ‘elaborating and defining’ the consensus of the powerful: ‘those who have a vested interest in commonly held opinions’.

In light of this, Fernandes examines the AUKUS treaty of 2021 where Australia agreed to buy eight nuclear-powered submarines and entrenched interoperability with US and UK forces. For the purposes of self-defense, Australia has no need for nuclear-powered submarines, which are much more expensive. But as part of global power projection by the US, they make more sense.

US and Australian hostility to Chinese ascendency make sense in the context of its threat to the US-led order.

Fernandes’ book is wonderful because its claims accomplish two things at once: 1. they run against Australian political orthodoxy, and 2. they are very obvious, in the way that an original assertion can immediately appear obvious by sheer virtue of its truth.

It’s also a short book. Fernandes writes clearly, not in the jargon too often preferred by academics. His style underlines his denouncement of faux expertise. There is a dry wit that courses through the pages. Comedy ensues as Australia pretends to be anything other than a sub-imperial power. For example, certain members of the US congress have more access to Australian defense information than Australian parliamentarians. Or how Australia about-faced on a nuclear India. India has not signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, and after condemning Indian nuclear tests in 1998 as “an outrageous act of nuclear bastardry”, a Labor-government supported an exception for India under a US-India nuclear deal and agreed to sell it uranium. Naturally, at the behest of Washington. Published WikiLeaks cabled revealed Australia would back the US in a war against China. New seasons of Utopia await. I got the same sense of comedy at times reading Hugh White’s excellent How to Defend Australia. Perhaps the inherent conditions of Australian defense and foreign policy are so ridiculous and their dissonance with public discourse and Australian self-conception so surreal that any meaningful assessment can’t help but read satirically.

Sub-Imperial Power provides a crucial piece of context. Hugh White’s How to Defend Australia, for example, presumes there is a national debate to be had on defense and foreign policy. It’s the gold standard of strategic assessment for Australia. It is acerbic in its assessment of Australia’s military strategy, or lack thereof, which is plagued by structural political misalignment, self-interested procurement decisions, and a host of other issues. It weighs the pros and cons of nuclear weapons and defers to the public and to policy makers. But what Fernandes shows is that you may as well ask the baboons at Taronga Zoo what they think. There is no forum for debate. The question for policy makers is never what do Australians want, but rather, what does the US expect of us? They do not ask how best do we defend this country? They ask how best do we stay front of mind for our US peers? Asking Australia to sit down and think through from first principles its defense policy would be like asking a Comanche whether he ought to be making war. Sure he could be an agrarian, but what has that to do with being a Comanche? Aligning itself with US hegemony, passed from the British, is all Australia has ever known.

US empire: a chain of unsinkable aircraft carriers?

The book is studded with factoids. Did you know China spends more on imported silicon chips than it does on oil? Or that just like Britain projected power onto Continental Europe in order to preserve a division of power there,

[t]he United States saw itself as an island off the coast of Eurasia, preserving a division of power across the Eurasian land mass… The United States sees Taiwan as an ‘unsinkable aircraft carrier’ at the centre of an island chain off the Chinese coast.

The US also has NATO to project force against the Eurasian landmass from the west. The UK too might be described as an unsinkable aircraft carrier. So might Japan. So might Australia.1 I find this map of the world as a series of countries functioning as American unsinkable aircraft carriers alluring. I think it is also true, but I’m not sure how useful a framing it is. How much does this add to the conventional story that America led the Allied victory in WWII, led the Cold War against the Soviet Union, and here we are?

Institutional conformity

Perhaps cribbing off Chomsky, Fernandes writes astutely about ideological institutional conformity and the selection for right-think:

Newcomers learn by various cues, explicit and subtle, to avoid certain topics. They begin to conform and to enjoy the privilege of conformity. They soon believe what they are saying because it is useful to believe it. Nobody in the system would get anywhere near higher levels of government unless they already shared the fundamental assumptions.

This seems to be right generally, describing ideological conformity across institutions.

Speaking of cribbing off Chomsky, apparently the Chinese Communist Party uses Chomsky’s work on ‘manufacturing consent’ as an instruction manual:

Noam Chomsky’s analysis of the American media system is ‘extremely influential among propaganda and mass communication theorists in China’. Chinese propagandists have studied Chomsky’s work with Edward Herman on ‘manufacturing consent’ and applied it to their own system.

The thing is…

The thing with this book though, is that it took me halfway to realise Fernandes was critical of Australia’s position. I was nodding away at Australia’s sub-imperial status like I sicko before realising Fernandes was critical of it. Sub-imperial power, I read — fantastic! Fernandes is critical of it. Why?

This comes down to the ‘lol’s I had running through the back half in particular. Fernandes makes bold unsubstantiated claims that assume a shared understanding with the reader. He speaks in a kind of NGO-ese, tut-tutting with throw-away lines on neoliberalism (it’s bad). Almost any time Fernandes makes an economic argument I cringe. And China is everywhere only an emergent benefactor, the US an overbearing bully.

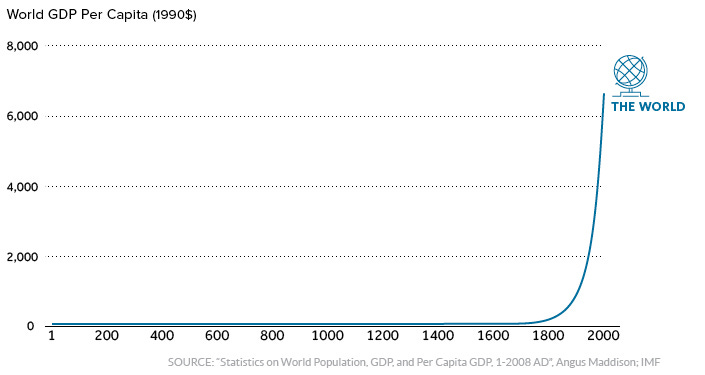

Fernandes admits several times that Australia is a net beneficiary of its sub-imperial status. It has prospered. It is a top destination for talent. Great! The American alliance is also very popular among Australians. All good reasons, to me, for Australia to maintain its posture. But Fernandes believes this is part of a broader conspiracy by US aligned nations to oppress and exploit developing countries, to keep them behind.2 He points to Britain handicapping the development of nascent Egyptian cotton-industry in the mid-1800s as an example of free market hypocrisy, and seems to imply Egypt could have been first-world if it had engaged in more protectionism. Maybe there are other reasons Egypt isn’t so advanced? One can believe that free markets are a cover for US power and economic chauvinism without believing a ‘Global South’ of nations are left poor and living under the boot of US economic hegemony by design. The stellar rise of the East Asia economies is a good counter example. South Korea had the GDP per capita of the Congo in 1960. The rise of China and India. Brought to you by Pax Americana.

China

His book ends with a warning, that Australia’s

stance will run up against China’s outreach to the developing world while the United States faces a deeply polarised political landscape and the prospect of democratic erosion.

‘Democratic erosion’ — come on. What a fizz to end on lame 2016 Democratic Party hysteria. SAD! And China, well, that’s the other thing. If the US is the evil empire in this story, China is the new kid on the block just trying to do the right thing and get along. These are some of the lines I marked ‘lol’ besides:

The Chinese government behaves respectfully towards these much smaller countries, who in turn are drawn to China’s promise of economic development

America’s aid is self-serving, China’s aid is beneficent. Fernandes honestly seems to take China’s call for a “more democratic international order” at face value. Which is obviously shocking (hilarious?) given China’s own authoritarian regime. But Fernandes stretches this much further. He refers to a large study that found

‘there was no real sign of burgeoning discontent among China’s main demographic groups, casting doubt on the idea that the country was facing a crisis of political legitimacy’

and

Marginalised groups in poorer, inland regions were more likely to be satisfied.

Without touching potential exceptions to this (Tibet? Uighurs?), I find it astonishing that an Australian academic would openly hail the political legitimacy of a one party ethno-state while tsk-ing the “democratic erosion” of the US. I suppose I’m open to the argument in principle — shall we talk about the legitimacy of the Franco or Mussolini regimes? — but it seems to be an underrated strain of radicalism in the book (in Australian academia?).

Maybe Fernandes’ weirdest China fetishisation is reserved for its ‘social resilience’:

In Wuhan, members of these neighbourhood committees went door-to-door to check temperatures and deliver food and medical supplies. Lacking a similar organisation that supports social resilience, Australia had to deploy its military and emergency services and hire private contractors.

Ah, that’s right. China’s famously moderate and non-militaristic response to COVID. Australia probably made many mistakes, but surely it did better than China and it’s not obvious at all it lacks some je ne sais quois communitarianism that Fernandes sees in China.

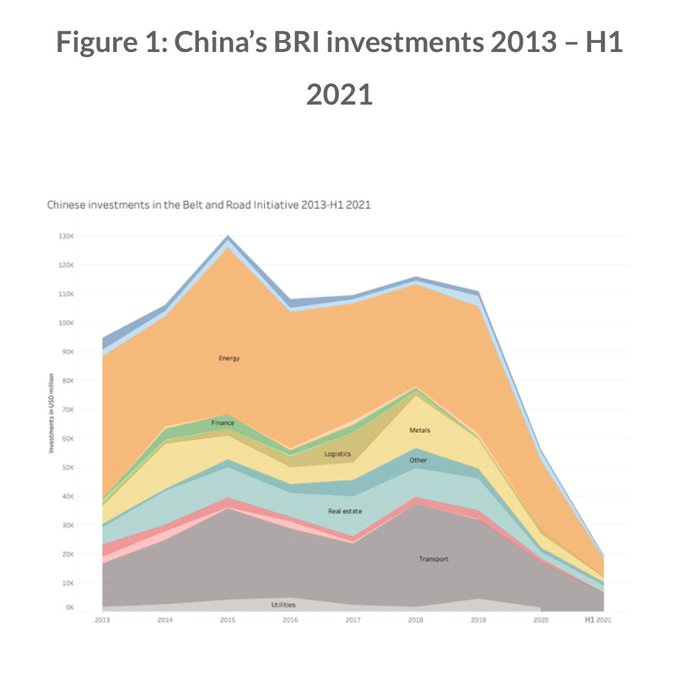

China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which Fernandes valorises, is hardly altruistic and was struggling even before COVID. It’s fallen further since:

Fernandes ultimately goes all in on Chinese moral superiority:

Today, China is the second largest economy in the world — a status achieves without resorting to slavery, war or colonialism.

The implication — hint hint — is that’s exactly how the West got rich. We stand atop the ashes of slavery, war and colonialism while the honest Chinese pulled themselves up by the bootstraps. Which is obviously false (Noah Smith has a good write up of it here). Moreover, China did not get rich in a vacuum — it got rich off Western tech, Navy-protected sea lanes, and consumer markets.

Fernandes describes how in earlier decades,

China left undeveloped the southern coastal provinces of Guangdong and Fujian, populated by tens of millions of people, because it expected to have to bomb them with its own air force to stave off an invasion by the United States or the regime in Taiwan.

Poor China… who backed the North Korean regime attack on South Korea? Who was saved from Japanese conquest by the Americans? I mean, come on!

Sub-imperial economy?

Fernandes’ broader economic commentary reveals a similar blind spot.

Australia has the lowest economic complexity of any OECD country. Fernandes blames this on its sub-imperial economy. Australia mainly produces a few primary goods that it sells into US value chains. But it’s not obvious Australia’s economy lacks complexity because of imperial economic demands. It seems more likely because Australia is so abundant in those resources? Its grazers and farmers have historically dominated its exports because Australia has had so much land for sheep. And it’s been blessed with world leading iron ore, gold, copper, lithium, bauxite, and other deposits. Fernandes compares Australia unfavorably with countries like Saudi Arabia and Kazakhstan. But he could easily compare it with Norway. Norway technically has more complexity due to a relatively small but highly advanced manufacturing sector. Australia has a shallower manufacturing sector. No doubt an idiosyncratic mix of path dependent histories and cultures led to that difference, but can we really say with confidence it is due to Australia’s role in empire? Seems an overfit onto Fernandes’ theory of everything for Australia.

Was Australia’s privatisation spree a means of enriching offshore (mainly US) investors? Or was it driven by domestic interests, with Australia having its own local political economy and self-enriching stakeholders (Cameron Murray wrote a great book about it called Rigged)? Latter seems more likely. Foreign investors carving up Australian mineral industry through foreign investment does not make sense. This is exactly what Fernandes contends:

Australia’s Department of Industry is a true believer in the doctrine of comparative advantage. Its Critical Minerals Strategy is not concerned with nation-building or increasing economic complexity but with creating a permissive environment for foreign investor to carve up Australia’s critical minerals.

Maybe the only thing that matters in the end is technology-driven productivity gains. That does not fit within Fernandes’ predatory framework. And the US is the principal driver today of software and medical innovation, and probably hardware too. One could flip the narrative entirely and paint a picture of Americans subsidising global growth through protected sea lanes, tech innovation and high domestic pharmaceutical prices.3

One Fernandes implication I find intriguing: Australia lacks all vision, any sense of what it wants to become, because it’s so constitutionally a cog in empire first. To ask what it wants to become, what it wants to build, does not make sense. This answers one vein of question I’ve bandied about in the past: why not build new cities? Anything orthogonal to its role as a sub-imperial power simply does not institutionally compute. I think there’s something to this. The US was founded by pioneers building something new, often inspired by religious zeal. There is sense of divine mission and chosen-ness. Australia was founded as a dumping ground for convicts and administrative extension.4 America revolted, Australia’s head of state is the British King. Politically, Australia is undoubtedly more subservient.

The neoliberal framework within which Australia has engaged with the region has not delivered optimal social outcomes. Why would it, given its track record?

Presumably “neoliberal” means something like the global capitalist US-order. He poo-poos the principle of comparative advantage. Fernandes shows how capital flows and intellectual properties (both of which tend to be American, by sheer volume) are protected from certain acts of parliament. US policy can be protectionist, chauvinist and uneven, favouring its own interests. But I don’t know how anyone can look around the world and consider the “track record” of capitalist growth since industrialisation anything but miraculous.

Sub-imperial power

That’s not to say that US and Australia come with clean hands. Fernandes works through examples of Australian belligerence, acting as an empire in its region and a lieutenant in foreign entanglements beside the US.

The Whitlam government condoned Indonesia’s invasion of Timor-Leste and the Fraser government recognised Indonesia’s sovereignty over it.

its military operations caused the deaths of about 31 per cent of the population — the largest loss of life relative to total population since World War II…

Australia sent weapons to Indonesia and shielded it from international criticism. Tim Fischer, deputy prime minister in the Howard government, praised Indonesian dictator Suharto as ‘perhaps the world’s greatest figure in the latter half of the twentieth century’.

The Australian government extracted oil and gas concessions, to which the Timor-Leste government has since objected.

While Australia’s extractive role in Timor-Leste is relatively well known, Fernandes goes further, claiming that Australia prioritised the creation of a small middle class in Timor-Leste at the expense of poverty eradication, resulting in rural poverty and migration to the cities where high unemployment persists. Here, Fernandes’ fevered dream is multilayered: an Australia that is so competent it can malevolently and successfully restructure a society to its benefit, and a counterfactual where ‘poverty eradication’ programs actually eradicate poverty from the country. Classic NGO-ese delusion.

Australian Secret Intelligence Service (ASIS) also helped the CIA overthrow the democratically elected government of Chile in 1973.5 Did you know that:

Under the cover of a foreign aid program, ASIS installed listening devices in Timor-Leste’s government offices to eavesdrop on its internal discussions during oil and gas negotiations with Australia.

Kind of cool to be honest, I didn’t appreciate the Australian intelligence services ever did anything useful.

Squaring the disagreement

Sub-Imperial Power has been well received in respectable leftist circles — like here and here. Branko Milanovic wrote a review on it here. I love-hate the book — some parts are essential to understanding Australia’s place in the world, and others are deeply misguided. But it’s worth it for its good parts alone — they are smart, pithy and counter-consensus.

Playing with a new map to explain this relationship. I agree with the author that America is an empire and Australia a sub-imperial power within it. But I think that’s good and he think that’s bad. Doesn’t feel right yet but here it is:

You could probably better characterise my view as: if you don’t like Pax Americana, boy you’d hate no Pax at all.

Another axis you might add would be: is US power waning or maxing? Bruno Maçães and Balaji Srinivasan would say waning. Ross Douthat might say, relative to others, waxing.

Israel too belongs in this group, as Fernandes notes critically. But it lies within the heart of darkness of Eurasia, a terrible outpost unprotected by oceans on all sides…

Did you know:

the United States tried to change other nations’ governments seventy-two times during the Cold War, with sixty-six covert operations and six overt ones… 28 per cent of covert operations targeted democracies.

Fernandes himself notes that

Americans sometimes pay up to ten times as much as Australians for identical pharmaceuticals.

Fernandes does try and refute this, endorsing a view of history that Australia was a strategic colony to project power in the region. I believe this is disputed at best. But I don’t think he needs this argument to make his case.

It’s a shame Fernandes has the habit of bungling a good point. Rather than say ASIS is immune to prosecution for any clandestine Chilean shenanigans and potential involvement in human rights violations by virtue of its US alignment, he has to say something as silly and quasi-Marxist as:

ASIS helped begin the global neoliberal class war. It is therefore exempt from an inquiry into its involvement

Good article. I’m willing to hear out critiques of American policy (after the total clusterf*** in Afghanistan, we need it), but waxing rhapsodic about Communist China is a good sign that one’s arguments are not to be taken seriously.

Well the US did save Australia's bacon in WWII.

Although I have become more sympathetic to some of Chomsky's critiques after the failures in Iraq (which I, to my shame, vehemently supported) and the current world craziness (including the Ukraine war and our failed attempt to mollify Iran), I always thought of him as halving half-opinions. One can lament our support of Indonesia very brutal treatment of Timor but then how can you make apologies for Pol Pot or Mao? The US is far from perfect but to think it would be better if China was the hegemon seems, well, naive to say the least. Let's think what happened during the era of US hegemony

1. World wide poverty fell by the most ever in history

2. China was allowed to prosper and become powerful (perhaps a mistake)

3. Democracy thrived in many areas which it had long been absent.

China is currently committing a real genocide against the Uighurs (and not for the first time in its history). How can you imagine that their hegemony would be anywhere near as benevolent as ours was? The US may often suck but you need to show a better realistic alternative before throwing it out.

One last story, when I was in grad student, a friend of mine who is now a very distinguished economic historian and Marxist went into a long harangue about how bad the enclosures were in 18th century England and that perhaps 20,000 people died because of them. I then said that it sounded similar to the holodomor in the Ukraine in the 1930 (which incidentally killed off my relatives who hadn't emigrated to the US). He said, no, collectivization was necessary in Russia and those deaths were inevitable. I was so shocked by that I couldn't reply.