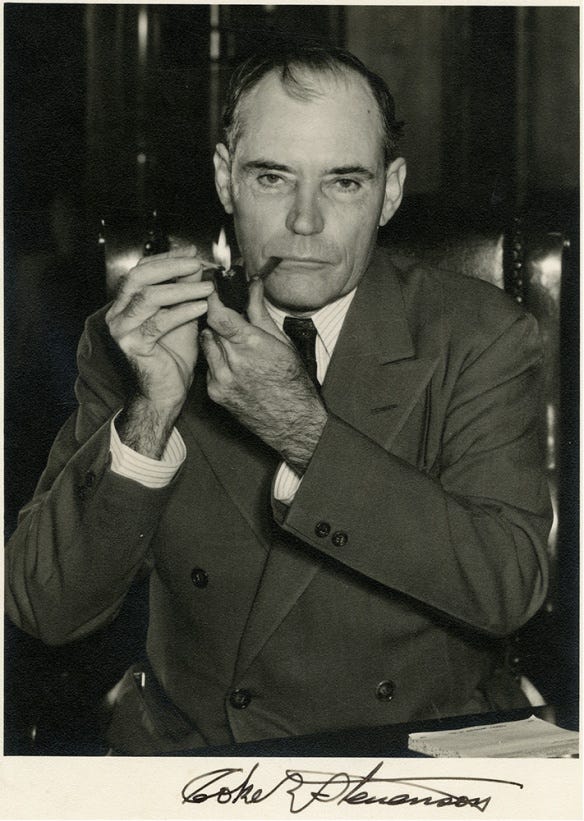

Coke Stevenson

A Texan Love Story

They had had the longest frontier in America; they had battled in close combat with foreign races; they had subjugated other peoples, and had been conquered themselves. They had learned that all peoples were not the same; parochial inside America, they were yet less parochial than those Americans who thought all the world was essentially the same. The great majority knew where their grandparents lay buried. They were as provincial as Frenchmen, as patriotic as Russian peasants. They put not their trust in governments, but in holding to their soil. These were things all Texans felt or sensed, though few could articulate well.

— T. R. Fehrenbach in Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans

I want to tell you about Coke Stevenson. Or rather, Robert Caro’s telling of Coke Stevenson in Means of Ascent, the second volume of Caro’s biography of President Lyndon Baines Johnson The Years of Lyndon Johnson.

There’s a lot to tell. How he defied conventional political wisdom against the mockery and scorn of journalists and won landslide elections with a record of delivering, a firm handshake, and his laconic Texan manner. Standing tall and erect, strong jawed and honest-eyed, how he defeated the populist candidate of the monied interests, the first-to-radio and folksy band campaigning of the Trump-esque grifter Pappy O’Daniel. How he became the most popular Governor in the history of Texas and a state legend.

But mostly, I want to tell you about his love story.

How his first beloved wife died of cancer and then at 66 he found love again with a beautiful 36 year old, and raised a daughter that bloomed a love that was as legendary as the man himself. His wife — so slight they called her Teeney — was an even better rifle shot than her husband and read a hundred books a year. His daughter was so precocious she read adult books at three in both English and Spanish.

I want to tell you this story because it’s hard to find such stories. Shining men on the hill. Partly it’s a testament to Robert Caro as a storyteller.

I wrote a whole series about the polygamous natural state of man and the fluky way Christianity built civilization on monogamy and modern family planning, framed in the unflattering light of male domestication, and the messy love lives of the forefathers in the Hebrew Bible. But here we have a man, a Real Man, the Strong Silent Type. A leader of men who came from nothing, from a poor part of a poor state, and rose through sheer competence and honest resolve to build a plot of land for himself and a pre-eminent place in his state’s history. A man who loved his wife and, long after she died, unexpectedly found love again. A man who loved his country and his people. A man who loved his own plot of land and worked every single day to improve it. Here is not a man yoked like an ox, by marriage or anything else. I don’t know whether his story represents the Platonic ideal for all men, or whether it’s just one beautiful manifestation of the Anglo-American Protestant. His life, his manner — the Texan vaquero, the hunter, the rancher — is a life that’s as distant to me personally as the Comanche. And like the lives of some of those Comanche men, I look upon his with moist eyes. For when we see Greatness — un-smeared by cynicism nor poisoned by irony — we must take note.

Below I extract from Robert Caro’s Means of Ascent. Extracts from earlier chapter give context to Coke Stevenson. Then I extract most of the penultimate chapter from Means of Ascent titled A Love Story (I have deleted parts for brevity).

After a bitter contest in 1948, meticulously detailed by Caro, where LBJ desperately fights for a senatorial seat he was sure to lose — lies, steals, bribes, cheats for it through endless twists — Coke Stevenson loses. Unfairly and un-squarely, he loses. LBJ would go on of course to become not just Senate Majority Leader, but President of the United States. Coke Stevenson returned to his ranch. And reading the story below, reading about this man with his devoted love to his first wife then to his second, his fatherly kindness to her son from a prior husband (a pilot shot down in WWII) and the legendary love for their own daughter, there can be no doubt whose life you’d prefer. Surely it is the life of Coke Stevenson, the Good Man, free from the insecurity and depravity and desperation that characterised LBJ’s life-long fight for power. And there is an ancient lesson in that, one we tell and re-tell, that rings through, clear as Texan spring water.

There are a few other choice details: Coke Stevenson’s friend and fellow widower moving in with him onto his ranch. How dutifully he cared for his mother in old age. The arrogant, self-serving and incorrect convictions of the journalist class. Texans’ self-conception and the mythology of Texas itself.

Coke Stevenson is only one character in Caro’s story of LBJ’s rise to power. But he’s an inspirational one. He showed how a good, strong man can defeat a populist grifter, Pappy O’Daniel, and can then lose — by the skin of his teeth — to the all-out machinations of a political genius. In Caro’s telling, he is the embodiment of what we dream of in our law-men and politicians. He approaches the ideal of objective principle and justice. Men may revere abstract ideals, but it is men and not those ideals that shape the world. Coke Stevenson believed in the law as fair and just and so it was. LBJ believed in the law as a means for his own accumulation of power and so it was. Abstractions become the men that inhabit them.

But then again, Caro really wrestles with the duality of each man. Caro nails LBJ — he’s amoral, power hungry, insecure — but clearly admires his achievements. Devoting his ferocious energy and brilliance to the education of his poor Mexican pupils as a teacher in a Texan backwater. Bringing electricity to the poor Texan Hill Country and in the process emancipating its farmers and their wives, bent from lugging water and chopping wood in near-Medieval serfdom. Ultimately passing the Civil Rights Act, the supreme achievement of mid-century liberalism. Caro admires Coke Stevenson but is wary of his conservative outlook. At one point — funnily and ridiculously — he attributes some of his reactionary outlook to a naivety borne of a lack of formal education.

There’s no neat lesson here — Good does not Triumph in the end. But nor must Evil. It’s up to each man to make exert what Will he can on the universe.

In the same way Coke Stevenson represents the best of a closing era in Texan history — the tough frontiersman that forged a nation in the face of Comanche and Mexican hostility — so does LBJ represent the opening of a new kind of politics. Caro writes about the “credibility gap” that emerged during LBJ’s presidential term, when the reverence the American people held for Franklin D. Roosevelt and prior presidents would be tarnished with cynicism and distrust. Over a century America transformed from “a collection of ragged colonies into an empire”1, from an Anglo-Protestant-forged frontier to urban centres infused by former farmers and new European migrants and rural blacks living under the umbrella of the Civil Rights Act LBJ ushered in. And this transformation is represented by these two men.

The open frontier was a great, unifying, imperial experience, and one that was continued for generations with only minor pain. But when the words of the song 'Across the Wide Missouri' were no longer a call to action or a spur to dreams but touched a profound nostalgia in the American mind, and the image of the Rio Grande recalled faded moonlight rather than hot blood, a certain sense of purpose departed from the American soul.

— T. R. Fehrenbach in Lone Star: A History of Texas and the Texans

Coke Stevenson

Coke Stevenson never talked long. His speeches were very simple. He made no campaign promises; a reporter was to write that Coke Stevenson never once in his entire career promised the people of Texas anything except to act as his conscience dictated. He had made a record in Austin, he said. The record was one of economy in government, of prudence and frugality, of spending the people’s money as carefully as if it had been his own, of having government do only what the people couldn’t do for themselves. That last point was very important, Stevenson said; it was always tempting to have government come in and solve problems, but every bit of government help came with strings of bureaucratic regulation attached, and every string was a limitation on the most important thing we possess, and have to leave our children—the thing that made Texas and America great. Freedom. Individual liberty. Every time that you accept a government program that you don’t really need, you’re giving up some of your freedom for a temporary gain; you’re selling your birthright for a mess of pottage. And Coke Stevenson speaking in front of the Courthouse impressed voters with the quality with which he had, as a young lawyer, once impressed juries inside. Says one political observer: “You knew he meant every word of what he was saying. You knew he was sincere. You just looked at him, and you said, ‘I can trust him.’” Journalists ridiculed this campaigner who refused to try to make news with his speeches or to make advance preparations, so that often he arrived in a town without anyone even knowing he was coming. But sometimes Stevenson would return to a town some weeks after his first appearance. And had the journalists not been so cynical, they might have observed that while on the first visit he had had to introduce himself around the Courthouse, on the second trip that would not be necessary. Nor, in fact, would it be necessary for him to walk into every office in the Courthouse. Recalls one politician: “The minute he got out of his car, the word would be passed: ‘Coke Stevenson’s here.’ And the people would come out of the Courthouse and the stores to meet him.” Not understanding the significance of this, however, journalists were startled when, in the first Democratic primary (the Democratic primaries were the crucial elections in a one-party state), this unlikely candidate defeated Senator Nelson, and three other candidates, to win a place in the runoff, although he finished 46,000 votes behind the leader, Pierce Brooks of Dallas. In the runoff against Brooks, Stevenson waged the same, seemingly foolish, type of campaign, and finished 46,000 votes ahead.

He ran for re-election in 1940, campaigning the same way he had before, again violating every aspect of conventional political wisdom. He had no platform, made no promises and almost no formal speeches, simply driving from one little town to another and talking to small groups of people. He had two opponents. One received 113,000 votes, the other 160,000. Stevenson polled 797,000. (That figure was 100,000 more than was polled in that same election by the still immensely popular O’Daniel, who, with an enlarged band, toured the state in a new campaign vehicle—a white bus topped with a papier-mâché dome of the Capitol.)

[Coke Stevenson’s wife] Fay had to be carried to the Inauguration. A few months earlier, doctors had told Coke she had cancer, and was going to die. She was placed in a wheelchair draped in red satin and carried onto the speakers’ stand, and, in the words of one observer, “remained smiling and radiant throughout the half hour’s ceremony.” She never appeared in public again. When she died, five months later, the Legislature commissioned her portrait, and it was hung in the Capitol.

In [the 1942] Democratic gubernatorial primary, the crucial election in a one-party state, Collins and the other four candidates received a total of 299,000 votes. Stevenson received 651,000. His 68.5 percent of the vote was the highest percentage that had ever been recorded in Texas in a contested Democratic primary. No candidate for Governor in the state’s history, not famous campaigners such as “Pa” Ferguson or Pat M. Neff or Dan Moody, not even Pappy O’Daniel himself, had won by so overwhelming a margin. In the general election that Fall, he again ran far ahead of O’Daniel. O’Daniel had stormed out of Fort Worth waving a flour sack in one hand and the Decalogue in the other and had become one of Texas’ greatest vote-getters. Coke Stevenson had ridden quietly out of the Hill Country and had campaigned without ever raising his voice—and had become an even greater vote-getter.

Strong and silent—Coke Stevenson’s personality was the embodiment of what Texans liked to think of as “Texan.” And so, indeed, was the whole story of his life, for in Texas, in 1941, the frontier was little more than a half century away. Some Texans had grown up on what still was the frontier; or their parents had, or their grandparents had, and had told them about it. The story of Coke Stevenson was a story they could relate to: when a Texan was told about making twenty miles a day—day after day, week after week, month after month—with a heavy-loaded wagon over rocky trails and across swollen streams, he could appreciate what that meant; Texans understood about the sleeping out in the rain, and about repairing the broken wheel spokes and rims and axles, about nursing the horses, and about loneliness. And it was Texans’ deep love for the land—the soil that they had had to fight so hard to wrest from the Indians and the elements—that made their Governor’s love of his land so meaningful to them. His hatred of bureaucracy, his distrust of the federal government, his belief in independence, hard work, free enterprise—all this struck a particularly clear chord in Texas. It was the “big country” that “fed big dreams” and that had drawn so many people fleeing the restrictions of a more orderly society, trading safety for danger, as long as with the danger came independence and the chance to create their own empires by their own efforts. It was a state, moreover, in which an unusually virulent mistrust of the federal government was a part of not-so-distant history; the settlers of the Texas frontier—and their descendants—firmly believed that the federal government had, inadvertently (some said, deliberately), protected the murderous Comanche raiders with its policy of not pursuing them and of preventing settlers from retaliating. And distrust of all government had been fostered by the Carpetbaggers—against whom, of course, the man for whom their Governor was named (“the lion-hearted Richard Coke”) had fought. Reinforcing Texans’ pride in their heritage was the fact that Texas had entered the union as an independent republic (it had been the Republic of Texas from 1836 to 1845). And Coke Stevenson’s image was Texas. He was, in the words of one headline, “AS TEXAN AS A STEER BRAND.” “Almost everybody calls him the ‘typical Texan,’ ” the Observer noted. He made Texans remember why they were proud of being Texans. As a San Antonio reporter put it in April, 1942, after she visited “that beloved individualist,” “Well, folks, Texas has a real Texan for Governor. The kind of man who has brought Texas fame in song and story. The kind that will give Texas back its faith in patriotism, in the ideals of 1776 and 1836. Coke Stevenson is like a fresh Texas Centennial celebration. He makes us live all over again many things that marked Texas pride and progress of a hundred years.”

A Love Story

The 1948 Texas senatorial campaign marked the end of the old ways in Texas politics and the beginning of the new.

The Johnson campaign taught Texas politicians the power of the media. “After that,” as Horace Busby puts it, “they saw that the way to reach the state was through radio.” And, of course, the state was becoming more urban, less rural. “The exodus from the small towns had started.” So, in subsequent statewide campaigns, candidates no longer campaigned as Coke Stevenson had campaigned in 1948. They no longer drove from one small town to the next. “You no longer made the circuit. The campaigning in the Courthouse Square died out. Coke’s campaign was the last campaign of that kind ever waged in Texas.”

But the story of Coke Stevenson was not over when the fight for the Senate seat ended.

It was to continue for twenty-seven more years, more than a quarter of a century, for he lived until 1975, when he was eighty-seven.

Stevenson went back to his ranch—and his old life. A longtime friend, hunting companion and fellow widower, Emil Loeffler, a former mayor of Junction, moved in with him. Until she died in 1952, Stevenson’s mother, who was in her eighties, would visit him for several weeks at a time; every morning, he would rise at four to read, cook the cornbread his mother liked, eat breakfast with her, and then, after washing the dishes, drive her around the ranch. Later, while she napped, he would do his chores, but only those that could be done near the house; during his mother’s visits Coke was never out of earshot of the house.

He had lost none of his desire to improve the ranch, which he now expanded to more than fifteen thousand acres; he sunk the poles for new fences and corrals, sledgehammering 120 posts into the hard Kimble County rock himself because the work was so hard that he could hire nobody to do it. He practiced law from an office in Junction (he still refused to install a telephone on the ranch; prospective clients who couldn’t find him in town had to drive out to the ranch), becoming a familiar figure again in the old Kimble County Courthouse. (To avoid any hint that he was using his influence with state officials he took cases mainly for Kimble County families he had known over the years “for fees … that I could write on a blackboard in my office for all to see and not be ashamed of a single one of them.”) Many of the state’s conservative business leaders had, once the excitement of the campaign had faded… realized they had been unjust to Stevenson, and they asked him to run—ample financing assured—for Tom Connally’s Senate seat in 1952; he would, after all, be only sixty-four years old, they pointed out. He declined. “I would not want to be the junior Senator to Lyndon Johnson,” he said. “It just wouldn’t work. My belief in principles is too strong.” He might run again, he said, but against Johnson—in 1954, when Johnson came up for re-election. To his friends, however, it was obvious that Stevenson had no enthusiasm for re-entering politics. “He hadn’t lost interest in politics; he still read the news magazines and all, but he had lost interest in his participation in politics,” his nephew, Bob Murphey, says. The stacks of mail—heavier than ever, containing now not only pleas for him to run but information on alleged 1948 vote frauds in scores of counties—piled up on the kitchen table, unanswered. His friends felt he was considering the race mainly because life on the ranch was, again, too lonely.

And then, in 1951, there was a new county clerk in the Courthouse. As a girl growing up on a Kimble County ranch, Marguerite King had been noted for her intelligence (“She was one of the brilliant ones,” a friend recalls), and for her ability as a rider and a rifle shot (“I learned to shoot before I could hold the stock steady against my shoulder; I’d lean it on a rock or something,” she says), but she had been nicknamed “Teeney” because she was barely five feet tall. Since then, she had left the Hill Country as one of the few young women from that isolated area to attend Baylor University, had married, been widowed when her husband, a pilot, had been shot down over Europe; and now, thirty-three years old, she had returned to Junction with her young son. But she was still petite and her nickname had stuck. “Teeney” was very quiet and serious, usually staying home reading (“biography, history—anything; I tried to read a hundred books a year”), but beneath the quietness was determination; in 1951, when the office of Kimble County Clerk became vacant, she ran for the job and was elected, becoming the first woman in the county’s history to hold elective office.

The new county clerk was strikingly attractive: slender and shapely, with keen blue eyes, what friends called a “whipped cream complexion” and glowing, tightly curled, golden hair. Her friends kept suggesting the names of eligible young men to her, but they weren’t interesting, she said; they didn’t have anything to talk about. They didn’t read.

She was still new to the job when, one day, Coke Stevenson came into her office to file a case, and she was unfamiliar with the procedures involved. She would never forget the quiet, calm, “kind” way he explained them to her. Then they began to chat. Recalling that day many years later, she says simply: “We found we had many things in common to talk about.” Stevenson was in the Courthouse frequently, of course, and they had more talks. “He loved his ranch and his land,” she recalls, “and he asked me if I’d like to come riding and see it. I would do that, and we would picnic on the river. That was how it all started, I guess.”

He invited her to go deer-hunting, and that proved a little embarrassing: famous hunter though Coke was, Teeney turned out to be the better shot. He was very good with her son, Dennis, then nine years old; years later, Marguerite would recall that Coke was a “gifted speaker, whether to an audience of hundreds concerning the serious affairs of the State or Nation, or to one little boy begging for the fiftieth time: Tell me about the time you shot the bear.’ ” She saw that Coke “doted on all children” and thought it was sad that Coke, Jr., now chairman of the State Liquor Control Board and a big man in Austin, didn’t visit the ranch more frequently so that Coke could see his two granddaughters. One day, when Bob Murphey came for a visit, instead of his uncle being alone, there was a beautiful woman with him. She seemed tiny beside Coke’s height and big shoulders, and was much younger. But Murphey realized that that didn’t matter. “I’ll never forget the way she looked at him, and the way he looked at her. Uncle Coke was in love, and Teeney was in love with him.” On January 16, 1954, without telling anyone—for Teeney hated “fuss” as much as Coke did—they slipped into a little church and asked the minister to marry them. (When the Junction Eagle learned of the wedding, the lead on its article told something of the near-reverence in which the groom was held: “Saturday, for the second time, Coke R. Stevenson, lawyer-ranchman and former Governor, took a bride from among his own people.”)

After they were married, when Coke rode out over his ranch, Teeney rode beside him; she was a good enough rider so that when he was working with cattle, she could work with him, although she couldn’t handle his big brown “cutting horse,” Nellie, and Coke found her a black named Elgin with a very smooth gait. When he was doing work with which she couldn’t help, such as clearing cedar or driving fenceposts, she would pack a lunch and bring it to him, and sit by him as he worked (worked, in his sixties now, hour after hour, swinging the huge sledgehammer as he had when he was young). Teeney seemed to want to spend every minute with Coke. Late in the afternoons they would swim in that beautiful river, with the herons and the cranes standing nearby, and the deer coming down to drink.

And as for Coke, he was a different man—or, rather, he was the man he had been when he was young, and had driven his car down the middle of the river on a bet. “I’m going to say a word about Mr. Stevenson now that you wouldn’t believe,” Bob Murphey says. “Bubbly. Uncle Coke was just bubbling. He just worshipped her.” Murphey had a wife himself now, and she says, “He never walked in the kitchen that he didn’t grab her and squeeze her and give her a big kiss. They were just so happy with each other!” Other friends, visiting the ranch, would watch Teeney and Coke reading together and talking. “They had the same kind of humor, the same way of looking at things,” Ernest Boyett says. “That dry way of observing people. They could sit and talk for hours. If that wasn’t happiness, I don’t know what was.”

And when, on January 16, 1956, the second anniversary of their marriage, they had a daughter, Jane, Coke Stevenson’s love for the little girl became, for the people of the Hill Country, a part of the story that had become, during his own lifetime, a legend to the people of Texas.

He gave her a precious possession that he had obtained for himself during countless mornings with his books. He gave her history.

As soon as the little girl was old enough to understand (and she was old enough very young; at three and a half she was not only reading adult books but could speak fluent Spanish), Stevenson began telling her stories—wonderful stories—about the history of the United States, and of Texas—and of Greece and Rome. After she started school, on days when snow or ice made the roads impassable and she couldn’t get to school, he and Teeney would take over her education themselves, reading to her. And when Jane was nine, Coke and Teeney started showing Jane history for herself. They had read her the accounts of the Alamo, of course, and of the battles of San Jacinto and Goliad and Sabine Pass, and they took her to all those sites, but they also ranged farther afield. They took her to see the Oregon Trail, reading Parkman’s The Oregon Trail as they drove; the three of them followed the trails of Lewis and Clark. “And many of the other Western trails, too, trails we never hear of,” Teeney recalls. “Coke knew all the trails.” There was the Revolution and the Founding Fathers, and there were trips to Mount Vernon and Monticello, and there was the Civil War, and all the battlefields that made up part of the history that Coke Stevenson loved. By the time Jane was a teenager, she had been taken by her mother and father to every one of the forty-eight states, and to several provinces of Canada, also. And there was a trip to a place nearer home. Coming home from school one evening when she was eleven, Jane told her father and mother that her class had begun studying how the state government worked. Coke took her to Austin so she could see it work for herself; once again, there was the whisper in the halls of the Capitol, “Coke Stevenson’s here,” and people came out of their offices into the halls to see a tall, erect old man holding by the hand a skinny little girl in pigtails.

And she appreciated the gift. “Jane was a good student, and a good historian,” Teeney says. “Those trips were good.” She loved history, and she and her father were very close. A reporter who spent several days with Coke when Jane was twelve was struck by the slim, pretty girl, and by her relationship with her father. “Stevenson is gentle-voiced with her, calls her ‘baby,’ ” the reporter wrote. “And you sense her love for the man who is big in her history books.” And when she became a teenager, Coke Stevenson made for Jane what was, for him, the ultimate sacrifice. Newspapers across Texas chronicled it in amazement: “A telephone has been installed on the Coke Stevenson Ranch.” “Well,” Stevenson drawled, “you know how teenagers are.”

“He idolized that girl. He told me many times that he hoped he would live to see her grown,” Bob Murphey says. He lived to see her nineteen years old and married to a young rancher, and not only did Coke live to a great age, respected throughout the Hill Country, a prophet with honor in his own country, but only in the last three or four years of his life did his health begin to fail; a reporter who went to see him wrote in 1959 that “at 71, the [former] Governor of Texas does hard manual labor six days a week.” All through the 1960s, as he neared eighty, he seemed never to be ill, and he still ranged from Wyoming to Montana to hunt the big elk. And he still worked on his ranch. He had decided to build at least rough roads connecting its fifteen thousand acres, and he did—ninety miles of them—and he took pride in every mile. He never lost his desire to learn new methods; deciding in about 1963, when he was seventy-five, that he wanted to build a large garage for his tractors and other ranch machinery, he decided also that he wanted to build it without supporting columns, so that maneuvering the vehicles would be simpler. Sending away for architectural textbooks, he taught himself the science of cantilevered construction, studying these books as eagerly as, fifty years before, he had studied books to teach himself accounting, and law, and highway construction. He never lost his self-reliance, and his happiness and pride when he did something on his own. And as for the law, “Well,” Teeney says, “Coke just loved the practice of law. And he had just the pick of cases now, from all over the state, and when he got a new case which was difficult,” where the legalities were complicated, he was as enthusiastic and as eager about studying up on the law involved as he had been when he had first started reading law books. His love of his land, the land he had saved so long to buy, and his pride in the improvements he had made on it were so deep that visitors constantly commented on it. Taken on a tour, a guest remarked on the clarity of the water in a large “tank” or pond. “I built that,” the host said. He had built it twenty years before, he said. The water was so clear because he had lined the pond with caliche, which he had lugged from another section of the ranch; sure, he said in response to the guest’s question, “It was a lot of work.” But, Coke Stevenson asked, surveying the results of his labor, “wasn’t it worth it?” If there was a single aspect of the ranch that was dearest to him—with the exception of the falls of the South Llano (“How he loved that river!” Teeney would recall)—it was the springs which kept the ranch green and his cattle watered even during droughts that turned the rest of the Hill Country brown. Every time he discovered a new spring his enthusiasm over the discovery would be as full and pure as the excitement of a young boy.

The love between Coke and Teeney was striking, too, as was the contentment they brought to each other. They were to have twenty-one years together, and they seemed to fall only more and more in love. When he rode his ranch, by horse or car, inspecting it or cutting out cattle, Teeney still rode with him; when he was doing work in which she couldn’t participate, she would still come, carrying lunch, and sit near him for hours as he worked. She began doing some of the research for his legal cases, so she was part of his life in the law, too. Says a friend: “It seemed like they couldn’t bear to be apart for a minute.” Says Murphey: “Uncle Coke told me many times how much joy she had brought him, and how he had never thought he would ever be this happy again.”

Teeney made sure that the Stevenson ranch was no longer isolated. Her husband had friends—from his days as a young legislator, in fact from his days as a young cowman—all over Texas, and now Teeney invited them for visits. “It was sort of an Open House,” one of these friends says. “There were a lot of bedrooms in that house, and sometimes it seemed like they were all filled.” In the evenings, Stevenson and his guests would sit around a mesquite campfire by the river drinking Ten High whiskey and swapping stories, while Coke got a good scorch on the steaks as big as saddle blankets.

Coke Stevenson and Lyndon Johnson never saw each other again. Stevenson’s hatred and contempt for Johnson never faded, and occasionally it would surface. Asked once, during Johnson’s 1964 campaign for the presidency, to evaluate him, he said, after a long pause: “Well, of course, he is a very, how should I say, skillful politician,” and dropped the subject except to say that he himself would vote for Goldwater. “I’ve been waiting a long time to see a turn toward conservatism.” Those who knew him well knew there were still scars from the 1948 campaign.

But the scars were smoothed over by happiness. From the day Teeney agreed to marry him, Stevenson never again thought seriously about running in the 1954 campaign against Johnson—or in any other campaign. He simply had no interest in public office. His dream, after all, the dream he had conceived during those nights so long ago on the Brady-Junction trail when six horses had been all he owned, had not been to be Governor, or Senator. His dream had been to be a rancher. And now he could enjoy the realization of that dream. “He would have made a great Senator,” Teeney says. “But he loved his ranch, and the life out here, and he loved practicing law. His life out here was more meaningful for him than it would have been any other way. And he knew that. He understood himself.”

A columnist for the Dallas News, Frank X. Tolbert, came to visit the former Governor. Observing Stevenson’s joy in the ranch, in the boyhood dream that he had turned into reality, witnessing the enthusiasm with which he still planned and built each new improvement, seeing the serenity of the quiet evenings by the river he loved, the affection between him and his wife, the love and respect in which he was held by wife, daughter, friends—by everyone around him—Tolbert wrote: “After spending some time with Coke Robert Stevenson … here by the green, rushing river, I’m wondering if he wasn’t lucky to lose that Senate race by 87 votes.”

Those who knew Coke Stevenson didn’t wonder. Bob Murphey, who had witnessed, better than anyone else, how hard his Uncle Coke had tried to win the Senate race, says, “Thinking back on it now, I truly believe that getting beat for the Senate and marrying Teeney was the best thing that could have happened to him.”

And a reporter who came to do a profile on the former Governor in 1969, when Stevenson was eighty-one years old, didn’t wonder. Watching Teeney come to meet him, the reporter wrote, “You sense … a protective motherly manner as she approaches her gray bear of a husband”—not that her husband seemed to need protection; he worked, the reporter wrote, “like a ditchdigger.” Teeney insisted that Coke show the reporter the historic marker that had been erected by the Texas State Historical Commission on the lawn of the Kimble County Courthouse. The marker had been placed in honor of a Texas institution. “Coke R. Stevenson,” it began. “Strong, Resourceful, Conservative Governor …” The reporter realized he was talking to “the only man in Texas who can look out his office window and see his own monument.” He realized how proud Coke was of the marker—at least partly because it bore the key word. “A conservative—he’s one who holds things together,” he told the reporter. “He shouldn’t fight all progressive movements, but he should be the balance wheel to hold the movement to where it won’t get out of hand.” He had been a conservative Governor, he said. “When I left office I left a thirty-five million dollar surplus.” He mentioned the old-age pensions he had tripled and the public welfare payments he had increased and the prison reforms and the more humane treatment in state institutions for the insane, and the reporter realized how very proud Coke Stevenson was of his whole life. Then Teeney and Coke drove the reporter out to the ranch, and he saw the house, and the love with which it was filled.

Finally, they went down to the river. A rowboat was there, and Coke explained that “Jane rows upstream, me downstream,” and Teeney broke in to say with a smile: “Then they both get tired, and I have to row.” A recent flash flood had changed the contours of the banks, and as the boat moved along, Coke Stevenson, eighty-one years old, suddenly jumped up in the boat and shouted, pointing excitedly at an Indian burial mound that the flood had uncovered. And there were springs, new springs. “There’s another one,” he said. “And look! There’s another!”

“He takes in the whole scene, waterfalls and deer and turkey and gentle flow of river,” the whole panorama of the beautiful canyon, the reporter wrote. And then, still standing up in the boat, Coke Stevenson threw his arms wide, in a gesture of triumph and joy.

Master of the Senate, Robert Caro

This is a beautiful post. I don't align politically with Stevenson--I don't see how such an intelligent person could've voted for a nut like Goldwater--but he sounds like a rare and wonderful human being. "For when we see Greatness — un-smeared by cynicism and poisoned by irony — we must take note." I couldn't agree more. A reminder that I have got to read the Caro books.

Thanks, a wonderful story. It seems that Caro received considerable criticism for this account, essentially from LBJ loyalists who represent the modern "consensus". Caro's reply to his critics ("My Search for Coke Stevenson" is also well worth reading:

https://archive.is/ZsBJc