Comancheria: Season 3

A new empire is born and the Comanches' last stand

Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.

— Chivington

Carson’s grim subordinate Captain, later Colonel, Pfeiffer, of the New Mexico territorials, had buried the mutilated bodies of his wife and her maid, seized by Indians while on a picnic outing. Pfeiffer became a legend in his own time, not only among shocked whites, but among the Amerindians, who said that whenever he rode out, the wolves came down from the mountains and hovered behind his column, certain of Indian carrion. It was Pfeiffer, as Carson’s good right hand, who trapped the Navajos in the Canyon de Chelly in 1864 and destroyed them so completely that they never made war on white men again.

— T.R Fehrenbach

…the Plains Dakotas were to become Episcopalians, and Ulysses S. Grant, either with the utmost sincerity or with a sardonic sense of humor, gave over the stewardship of the Comanche people to the Quakers.

— T.R Fehrenbach

RECAP: I sketch out three seasons of Comancheria, stitched together with bullet point summaries and extracts from T.R Fehrenbach’s superb and underrated Comanches: The History of a People. Each episode is a self-contained vignette, following a broadly chronological arc. Fehrenbach’s mesmerising prose brings to life one of the last great frontiers of history.

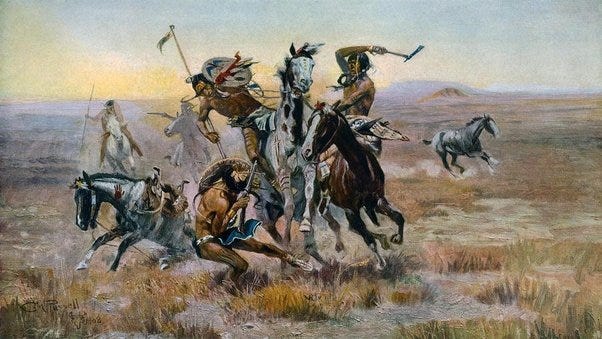

In this third and final season we follow the violence of Plains Tribes raids and United States army counterraids, with some astonishing stories such as that of Britt Johnson. In the aftermath of the Civil War, the United States turns its gaze out west and the army’s retribution becomes defining. The Plains Tribes are defeated, as much by disease and the sheer weight of settlers and migrants going West as by the soldiery. Trains and mines and industry lay waste to the great bison herds on which the Plains Tribes rely. The final gasp of a warrior people is extinguished. Immiseration as wards of the state follows in the tragi-farcical machinations of Church stewards and false promises and broken treaties and a horribly corrupt bureau. Only dreams of a distant past on the plains for the Comanche remain, as a new empire rises.

For something in their lives—the hot thrill of the chase, the horses running in the wind, the lance and shield and war whoop brandished against man’s fate, their defiance to the bitter end—will always pull at powerful blood memories buried in all of us.

— Fehrenbach

Season 1: Rise of Comancheria

Episode 1: Chaos

Episode 2: Comanches and Apaches

Episode 3: New Spain and Villasur — 1720

Episode 4: The Massacre of San Saba — 1757

Episode 5: Don Juan Bautista de Anza and Truce — 1786

Episode 6: New Spain Terror and Decline

Episode 7: Mexico and Hell

Season 2: Comanchería y el Tejano Diablo

Episode 1: Parker’s Fort — 1834

Episode 2: Rise of the Texan Ranger — el Tejano Diablo

Episode 3: Lies and Destruction of the Cherokees — 1839

Episode 4: Council House Fight — 1840

Episode 5: The Battle of Plum Creek — 1840

Episode 6: The 2nd Cavalry — 1855

Episode 7: Lieutenant Hood - 1857

Episode 8: John S. Ford — 1858

Episode 9: Robert Neighbors — 1859

Season 3: Comancheria’s Last Stand (**THIS WEEK**)

Episode 1: The Chivington Massacre — 1864

Episode 2: Civil War Respite — A Close Call — 1864

Episode 3: Little Buffalo and Britt Johnson — 1864

Episode 4: Colonel Pfeiffer — 1864

Episode 5: Mackenzie and his Buffalo Soldiers — 1872

Episode 6: Empire Out West

Episode 7: Eeshatai, Quanah and the Last Stand — 1874

Season 3: Comancheria’s Last Stand

Episode 1. Chivington massacre — 1864

The Indian-fighting regiment recruited in Denver in the summer of 1864 was mustered in an atmosphere of hatred and hysteria. This was the summer that the Cheyennes and Comanches and their allies ran amok, destroying communications and trapping hundreds of hapless travelers. Cut off, the Colorado mining camps were almost starving. J. M. Chivington, the former Methodist minister who was now a brigadier general in the Army of the United States, the officer who had saved New Mexico for the Union, enlisted his territorial volunteers for one purpose: to destroy Indians. To spur recruiting, the mutilated corpses of a white immigrant, his wife, and two children were displayed in the center of Denver beside the drum and enlistment table. Chivington did not dissemble. He instructed his regiment: “Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.”

The Colorado territorials attacked a large encampment of Cheyennes on Sand Creek. This was the village of Black Kettle, who had been at war but had recently made truce and, according to some accounts, flew the American flag above his tipi. The volunteers came down on the camp. They bombarded the tipis with howitzer shells, then raced among the tents, stabbing and shooting. When the screaming and bloodlust was over, there were three hundred Cheyenne bodies scattered along Sand Creek. Twenty-six of these were warriors; the rest were women and children. Throughout the entire territory, Chivington’s coup was hailed as a great victory.

The great difference between the Chivington massacre and at least a dozen similar actions was simply that Chivington, who by his own lights was a hero, received more publicity. Many of his volunteers shot squaws and bayoneted Cheyenne children with relish, but the heterogeneous Colorado column also contained many men whose stomachs revolted. As detailed descriptions, which were rare in the West, emerged and were published in newspapers, a wave of horror swept the distant East. But significantly, a fact not always noted by historians, the outcry was confined to the East and to the regular army, which disavowed Chivington as a volunteer officer and forced him to resign to avoid court-martial. No action was or could be brought against the regiment, as it had passed out of service.

Episode 2. Civil War Respite — A Close Call — 1864

THE RESPITE GIVEN THE PLAINS TRIBES BY THE CIVIL WAR WAS NOT enough to allow them to rebuild their numbers. In the closing months of that conflict, the United States military commands in the West were moving swiftly to regain the initiative and effect a bloody retribution. While the Colorado militia was mopping up Amerindian villages without regard to guilt or innocence in the wars, Colonel Kit Carson of the New Mexico Territorials had crushed the Navajos. By the fall of 1864, Carson’s superior, the district commander General James H. Carleton, was ready to turn the army’s attention to the Comanches and Kiowas, who all year had raised havoc along the Santa Fe Trail.

Angry bands of southern warriors threatened to cut completely this route of communications with Missouri and the East. During 1864, virtually every wagon train proceeding down the Canadian River to New Mexico was attacked. Even large and powerful parties lost horses and oxen to raiding Amerindians. Small groups, whether military or civilian, had been massacred. In October, therefore, Carleton received orders to restore full communications and to “punish the savages” responsible for the depredations. He authorized Colonel Carson to sweep through the valley of the Canadian with a strong force of New Mexico and California territorials.

It was known that large numbers of Comanches and Kiowas were wintering on the rich bison plains of the Texas Panhandle, and it was believed that these Indians would not be prepared to fight a winter campaign.

Carson marched out of Cimarron, New Mexico, in early November with more than three hundred mounted troops and seventy-two Ute and Jicarilla Apache scouts and auxiliaries. The Utes were promised scalps and plunder, and some warriors brought along their women. Carson was well supplied: he had a well-stocked train of twenty-seven wagons and six thousand rounds of ammunition. He was also furnished with two excellent little twelve-pounder mountain howitzers, fitted on special traveling carriages.

He was in sight of the Indian camp at daybreak. Lieutenant George Pettis of the California volunteers, the officer in charge of the two-gun battery, thought he saw gray-white Sibley tents in the distance. Carson informed him that these were the sun-bleached tipis of Plains Indians. The Utes reported a camp or village of 176 lodges. Without scouting farther down the river valley, Carson detached his baggage train with a guard of seventy-five men, and with a squadron of some 250 cavalry attacked across the two-mile-wide valley toward the village. This was open country, surrounded by low hills or ridges, and covered with dry grasses that rose horse-high in many places.

The Ute and Jicarilla auxiliaries left the column and tried to steal the enemies’ horse herd. The camp, which was Kiowa Apache, was alerted before the cavalry reached it. The warriors formed a skirmish line to cover the flight of their women and children, who abandoned the tipis and ran for the ridges behind the river. The Kiowa Apaches formed an integral part of the Kiowa tribal circle, and on this day one of the great war chiefs of the Kiowas, Dohasan (To’hau-sen, Little Mountain, also often called Sierrito), was in their lodges. Dohasan organized the defense, while also sending for help from Comanche and Kiowa lodges downstream. He rallied the warriors, and his swirling, shooting horsemen slowed the white attack and assured the escape of the women. Carson’s cavalry killed one warrior who wore a coat of mail, but when they reached the tipis they were deserted.

Dohasan exhibited great bravery. His horse was shot from under him, but he was rescued and rallied his warriors. The cavalry pushed on against the retreating Kiowa Apaches for about four miles, finally reaching the crumbling Adobe Walls buildings. Here, more and more Indians seemed to be appearing. The whites dismounted, and sheltering their horses behind the trading post, began skirmishing on foot. Carson came up to Adobe Walls with the battery, and now both the old mountain man and the inexperienced Pettis saw another camp of some five hundred lodges rising less than a mile away, along the river.

This was a Comanche encampment, and hundreds of warriors were streaming from it across the prairie. Pettis counted “twelve or fourteen hundred.” The Indians formed a long line across the ridges, painting their faces while their chiefs harangued them. The Kiowas, who were also arriving in large numbers, roared the battle songs of their warrior societies. Pettis feared that the horde would charge the white squadron at any moment.

Carson ordered him to throw a few shells at the crowd of Indians. The howitzers were unlimbered, wheeled around, and fired in rapid succession. The shells, screaming over the warriors’ heads and bursting just beyond them, seemed to startle the Indians badly. Yelling, the host moved precipitously out of range.

Carson told his troops that the battle was over. He ordered the horses watered in Bent’s Creek. The surgeon looked after several wounded men while the others ate cold rations. However, the tall grass was swarming with distant Comanches and Kiowas. Within the hour, a thousand warriors surrounded the trading post, circling and firing from under their horses’ bellies. Surprisingly, most of the warriors appeared to be equipped with good firearms. However, the twin cannon broke up their attacks, and the exploding shells knocked down both men and horses at a great distance. The enemy swirled about for several hours, not daring to press too close, while the howitzers killed many on the ridges. But Carson was becoming apprehensive. He had never seen so many Indians. Pettis was sure that there were at least three thousand, and small parties could be seen still arriving. The expedition had marched unwittingly into a vast winter concentration of the tribes on the southern bison range. Carson, with a split command, was worried about his trains. His rear detachment, without cannon, would almost certainly be overwhelmed if the enemy discovered it. He now made a cautious but quite sensible decision: to break out of Adobe Walls and regroup with his supply column, which had his food and ammunition.

The cavalry mounted and retreated behind the fires of the battery, which stayed constantly in action. The Indians fired the grass, but this helped, because the smoke concealed Carson’s retiring column. About sundown, the whites arrived back in the deserted Kiowa Apache camp, where Pettis noted that the Ute women had mutilated the corpses of several dead Indians. Carson ordered the lodges fired; then, under the cover of darkness, he moved out rapidly to the west. The enemy did not attack. Three hours later, he rejoined his wagons.

The next dawn, the Indians still held back. Some of the territorial officers insisted that the expedition take up the attack, but Carson ordered a withdrawal. The odds were much too great; Carson, who later wrote that he had never seen Indians who fought with such dash and courage until they were shaken by his artillery, did not make the error of despising horse Indians. He had so far lost only a few dead, and a handful of wounded, while his guns had inflicted serious losses, killing and wounding perhaps two hundred Indians. He could claim a victory, and did this when the column arrived back in New Mexico. Carson’s official report stated that he had “taught these Indians a severe lesson,” to be “more cautious about how they engage a force of civilized troops.”

Privately, he thought himself lucky to have extricated his command.

Episode 3. Little Buffalo and Britt Johnson — 1864

On October 13th Little Buffalo’s horde crossed the Brazos about ten miles above Fort Belknap, where Elm Creek poured into the river. The Comanches and Kiowas swarmed up the creek bottoms, which were inhabited by between fifty and sixty stubborn white frontier people. The raiders, bold in their numbers, split and rode along both banks at noon on a bright, crisp, beautiful day. The burning and killing began.

The Comanches came upon a settler and his son, who were looking in the brush for strayed livestock. They killed, stripped, and mutilated the man and boy. They then moved along the creek to the Fitzpatrick ranch. Here there were three women and a number of children. The men were away, gathering supplies at the Weatherford trading post. As the Indians rode up, young Susan Durgan seized a gun and rushed outside. She fired on the warriors, but they cut her down and stripped her naked, mutilated her corpse and left it lying in the yard. They captured the other women and children: Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, Mary Johnson—the wife of Nigger Britt Johnson, a black man who was legally a slave but treated as a free man on this frontier by an owner who had inherited him—and three black and three white youngsters. Two warriors quarreled over who had seized the oldest black child, and settled the matter by killing the boy. The women, the two surviving Negro children, young Joe Carter, aged twelve, and Lottie and Millie Durgan, aged three and eighteen months, were carried off.

The two Hamby men, with Tom (Doc) Wilson, rushed for the George Bragg ranch house, which was a small but picketed and sodded cabin, built to serve as a fort. As the three men abandoned their horses in the ranch yard, Doc Wilson was struck in the heart by an arrow. He staggered into the house, jerked the missile free, and died in a gush of blood. George Bragg, five white women, a Negro girl, and a large brood of children were in the house. The ranch was immediately surrounded by a horde of howling warriors. With young Hamby coolly directing the defense, the whites prepared to stand off a siege.

The women were directed to reload all the rifles and pistols. One woman stood at Thornton Hamby’s elbow and gave him great assistance. As the Comanches rushed the cabin, trying to dig out the pickets, he opened fire from the tiny gun ports that were a feature of all west Texas ranch houses. The elder Hamby killed one Indian, but he had suffered four wounds, and old George Bragg was not much help. Young Hamby saved the whites as he emptied pistol after pistol pressed into his hands by the desperate women who reloaded them at a table. All afternoon, while some unseen warrior blew mournfully on a captured army bugle, Hamby held the fort. He was wounded again; then he killed Little Buffalo himself, who was directing the attack, with a lucky shot. The Comanches withdrew, after a few parting shots and a bugle blast.

…

The Elm Creek raid had its aftermath, as did every Comanche descent. Britt Johnson returned to the Fitzpatrick ranch to find his son buried, his wife and two small children gone. Johnson was determined to rescue his family. With the help of the Hambys and others, he got together a pack horse, provisions, a rifle and two six-shooters, and struck out north-northwest, into the vast wilderness that lay beyond the Brazos settlements.

After covering sixty miles, the courageous black frontiersman reached the Wichita River. Here he came across a lone Comanche guarding a horse herd. Johnson could “talk Mexican,” which most Comanches and Kiowas understood, and he made the peace sign and advanced boldly. The warrior, and a party of Comanches who rode up, were more curious than hostile, and they accepted truce with the black man. Some of the Comanches were Pehnahterkuh who had been at the Clear Fork Reservation, and they remembered Johnson. Johnson, meanwhile, ignored the fact that he recognized the Peveler and Johnson brands on some of the Comanche horses. He had found some of the raiders.

The friendly Pehnahterkuh told Johnson that there was a single white woman in their camp, but that the Kiowas had taken all the negros. They agreed to let him ride with them to the encampment. This meeting, and the casual truce Johnson forged, was an immense stroke of luck. From now forward he enjoyed hospitality, and even a certain interest among the Comanches in his project.

He found Elizabeth Fitzpatrick in the camp, which lay somewhere on the high Canadian. From her he learned that Little Buffalo and twenty warriors had been killed at Elm Creek, which had caused the great war party to break off and retreat. On the return, the Comanches had killed little Joe Carter, Mrs. Fitzpatrick’s son by a former marriage, because the boy took sick. The two Durgan children and Johnson’s family had been taken by Kiowas. Elizabeth Fitzpatrick begged Britt Johnson to try to ransom all of them; she was a relatively rich woman in Texas and would pay any price.

Johnson now made four incredible journeys into the heart of Comanchería, searching for the captives. He could not have succeeded without the good offices of the friendly Pehnahterkuh, who not only instructed him in dealings with the “tricky Kiowas” but gave him two warriors for escort. He made a deal for Elizabeth Fitzpatrick and brought her out. He located his wife and bought her back for the equivalent of two dollars and a half. He also ransomed his children and little Lottie Durgan, Mrs. Fitzpatrick’s granddaughter. He failed to bring out Millie Durgan; she had been adopted into the family of the Koh-eet-senko Aperian Crow and was not for sale.

Elizabeth Fitzpatrick, who owned much land and many cattle, fared better on return than most captives; she was able to marry again. Johnson’s indomitable efforts bespoke his own feelings for his wife, and her return was a happy one. There was grief over the Durgan child, who was never seen again. However, the grief was perhaps misplaced. Sixty-six years afterward, the old Kiowa woman Saintohoodi Goombi was identified at Lawton, Oklahoma, as the Durgan girl. Her life had not been an unhappy one. In the clannish Kiowa circles she had been raised as the daughter of a great chief; she had married and reared a family. She had no memory of her origins or white blood, and when she died in 1934, she had made it clear that she desired nothing whatever from her former people.

Nigger Britt, meanwhile, had won the respect of the entire white frontier. After the war, in a Texas harvesting the bitter fruits of Reconstruction, he opened a successful freighting business in partnership with three other former slaves, carting supplies between Weatherford and the army forts that were eventually rebuilt in the west. This was extremely dangerous business on this Comanche-infested frontier, but then, as the Brazos country agreed, Britt Johnson was an extremely courageous man.

Episode 4. Colonel Pfeiffer — 1864

For many of the territorial volunteers the Indian wars had become personal. The old hands, such as Jim Bridger, who advised and scouted for the army, and Kit Carson, who commanded the New Mexico militia, had lived among the tribes and kept a certain equanimity. They understood the humanity of the Amerindians beneath their barbarity. But these men were in a minority. Carson’s grim subordinate Captain, later Colonel, Pfeiffer, of the New Mexico territorials, had buried the mutilated bodies of his wife and her maid, seized by Indians while on a picnic outing. Pfeiffer became a legend in his own time, not only among shocked whites, but among the Amerindians, who said that whenever he rode out, the wolves came down from the mountains and hovered behind his column, certain of Indian carrion. It was Pfeiffer, as Carson’s good right hand, who trapped the Navajos in the Canyon de Chelly in 1864 and destroyed them so completely that they never made war on white men again. Despite requests of the regular military establishment for magnanimity and rehabilitation of the stock-raising Navajos, the survivors were herded into arid country and left to starve by the territorial forces. It was these Navajos that Carleton, the Union commander in New Mexico, saved by putting his own soldiers on half rations and feeding the Indians through the winter.

Episode 5. Mackenzie and his Buffalo Soldiers — 1872

Ranald Mackenzie became and remained the best Indian fighter in the West. He combined great military talents: the initiative to operate under mission-type orders, needing nothing spelled out for him; the ability to pay minute attention to detail, while never losing an almost incredible aggressiveness. It went without saying that he was fearless, both of others’ opinions and the enemy. Mackenzie made the Negro cavalry a splendid military instrument; he refined the plains tactics of the army in countless ways, from using infantry in wagons as mobile weapons platforms to the use of multiple columns in the techniques of pursuit. Above all, he brought the cavalry back to the practice of the relentless hunt, the most effective of all measures against guerrilla tactics. He organized and carried out the destruction of Comanche resistance on the plains; he then destroyed the Cheyennes to the north; and his techniques were consciously adopted by all later commanders for all Indian operations, from the Dakotas to Arizona. But Mackenzie was to be one of the most tragic American military figures, who after decisive accomplishments left the army in bitterness at the age of forty-two. Despite the fact that Grant described him as the most promising young officer in the army, he was to die forgotten, and to remain forgotten by his countrymen. Mackenzie could not fit the image of the standard American hero.

He was cold, remote, taciturn, utterly professional, a “monk in boots” who had no interests except in carrying out combat missions. He was not arrogant, capricious, unfair, or vain—his staff constantly attested to the high respect in which they held him. But Mackenzie was merciless where the performance of duty was concerned. He was hard on officers, hard on men, hard on horses, and hardest of all upon himself. He did not build “smart regiments” but unkempt, long-haired, dirty-uniformed Indian killers. He took his illiterate mercenaries, black and white, and made them almost as efficient as himself. Mackenzie was no book soldier, whether in discarding bugles and sabers, or in spread-eagling every enlisted slacker against a wagon wheel. He would never be a popular hero, because his methods would not stand popular inspection. He and his black heroes, probably, had to be expunged from the popular history books, because he and his colored cavalry did not quite blend with the rising America’s image of itself.

He believed that the Comanches would be most vulnerable during the fall hunting season; he wanted to give them no chance to store their winter meat. He personally led a column of twenty Tonkawa scouts and 222 soldiers across west Texas, drawing new supplies in New Mexico. The patrolling paid off in late September 1872. The Tonkawas located Mow-way’s encampment on McClellan Creek, a branch running into the Red River, high in the Texas Panhandle.

As the delighted Texans said, Mackenzie dosed the Kuhtsoo-ehkuh with their own medicine. He came down on the village and destroyed it. At least fifty Comanches were killed and 130 captives taken. Significantly, perhaps, there were no adult males among the prisoners. The Buffalo Soldiers, as the Plains Amerindians called the black troopers to distinguish them from white men, burned everything—lodges, poles, hides, blankets, and all the drying winter meat. They also seized a huge herd of horses.

The great remuda was difficult to guard, and the following night several desperate warriors attacked, stampeding it. They also drove off some cavalry horses. After this Mackenzie gave standing orders that all captured Indian ponies must be shot at once.

In these operations the 4th Cavalry lost some twenty troopers killed or wounded, and the Comanches did recover all their horses. But the Kuhtsoo-ehkuh band was virtually destroyed, and the survivors were demoralized. Some warriors escaped, but their women and children were held by Mackenzie at Fort Concho. Representatives came in under flag of truce, asking for their return. The prisoners were not harmed; in fact, some of the ladies at Fort Concho tried to make friends with them. Mackenzie’s terms were simple: the Comanches must go to the reservation and return all white captives. The Kuhtsoo-ehkuh were humbled; they gave Mackenzie assurances of friendship, and there was an exchange of prisoners at the Sill agency.

Episode 6. Empire out West

The incompetence of the Office of Indian Affairs finally destroyed it, though its arguments and policies lingered on. By 1869 the corruption of this agency was so clearly known that the Congress, even in an era of rampant graft, abolished it. The President was authorized to form a new Indian commission, the Indian Bureau, which would have joint jurisdiction with the Interior Department over Indian affairs and appropriations. President Grant, a former soldier, wanted to turn the operation of the Indian agencies over to the army, as the army had long requested. However, Congress would not stand for this, and a compromise was reached by offering the agency posts to the nominees of various religious denominations, who, it was hoped, would be more honest than the former appointees, and would also pacify the tribes by converting them to Christianity. Probably neither Congress, the President, nor the various groups who immediately accepted the challenge—furnishing agents, teachers, and other employees—knew anything about the Hispanic experience in the Southwest. Thus the Plains Dakotas were to become Episcopalians, and Ulysses S. Grant, either with the utmost sincerity or with a sardonic sense of humor, gave over the stewardship of the Comanche people to the Quakers.

The policy was still peace, and many people in government believed that the Friendly Persuasion might bring about a reformation of the plains’ most unregenerate warriors.

The subjugation of the Indians by settlers and a corrupt government

Indians become wards of the state — a state that imposes cynical treaties and then breaks them in a perverse farce, and delivers them lies, starvation and death

Spasms of tribal brigandry, and permitted hunting — first of cattle provided, then chaperoned hunts onto the plains. But there were no more bison left — met by endless sea of bison bones. Contrasts against earlier scenes of joyous Comanche hunting of bison in the old days

In 1869, Phil Sheridan convinced Grant that treaty-making with the tribes was a travesty. If the Indians were wards of the federal government, they could not be autonomous nations. Grant agreed, and thus the hopes of the Comanches for new councils were shattered.

Thousands of sick new migrants going west, Comanches devastated by plague

Zooms out to fields of dead bison, followed my mountains of bison skulls and empty fields through which a train rides

The shooters slaughtered stand after stand; the lowly, sweating, stinking skinners stripped off the hides, leaving the carcasses to rot. Wagons filled with bloody hides rumbled into Fort Griffin, Fort Worth, and went on to Dodge City, for shipment over rails. Behind them, for miles and miles the high plateaus swarmed with circling vultures, which left acres of whitening bones.

Episode 7. Eeshatai, Quanah and the Last Stand — 1874

Eeshatai (Coyote Droppings) the medicine man was a phenomenon that had appeared, or would soon appear, among many disintegrating Amerindian peoples from the Southwest to the Pacific Northwest. He was less a symbol of hope than of extreme social decay and despair. He was a common reaction thrown up by despairing societies. He was a Nerm, and therefore he moved and spoke within the traditions and consciousness of the People. He reaffirmed the primacy of the spirit world, and he rallied the spirit world behind the People for war.

Eeshatai had not proved himself in war, but he was a young man who claimed powerful puha, medicine. He was immune to bullets, and he had performed certain miracles, such as bringing back the dead and belching forth a wagonload of cartridges.

This prophet moved through the bands during the spring of 1874, telling them that if they purified themselves, the time of deliverance was near. He professed a power that could save them from their enemies. By May he had gathered the restless remnants of the Comanches together north of the Red River as no past war chief had ever done. For the first time in the People’s history, a leader brought together almost all the lodges of the tribe in one encampment.

The ritual preparations continued for five days, with sham hunts and battles, invoking the memory of past glories. However, the Comanches did not plan to follow the masochistic practices of other northern tribes: there was to be no hanging from the pole by thongs attached to warriors’ breast tendons, no dancing with buffalo skulls dragged by cords passed through back muscles, nor dancing till exhaustion.

Eeshatai’s instinct was splendid, for all this fitted both Comanche spiritualism and cultural pragmatism.

At sundown on the fourth day of preparation, criers rode through the great assemblage of lodges, calling out every separate band to stand before their tipis. In their hundreds they began to chant their band songs and do their special dances. The Pehnahterkuh were not there, however, for they had heard the talk of Eeshatai that when the dance was over, all the People would unite, fall upon the whites and annihilate them, so that the bison could return to the plains. Everything would then be again as it had been; the People would again grow numerous and powerful. The People could not fail, for the power of Eeshatai would protect them; he would lend them his own invulnerability. The Pehnahterkuh in their pitiful remnants did not believe such talk. It frightened them, for they knew better than all the others the numbers and the power of the Texans. The Pehnahterkuh chiefs took their families far away, across the Red River, where a few other stragglers joined them.

But the other bands were united as they had never been. Now, before their lodges, they merged into one great mass of dancers, moving and stamping in a growing unison, until their feet, landing as one, shook the earth itself.

The People danced for three days to the drums, rattles, and eagle-bone whistles. Their singing roared out over the prairie. The drums pounded into the night while the dancers rested to prepare for the exertions of the morrow. For three days and nights they danced. Then, Eeshatai declared that the People were one; they were ready.

All night the warrior societies danced, while the prophet and Comanche and Cheyenne, Kiowa, and Arapaho war chiefs held council. With vast excitement, many of the warriors joined the People for this great war of extermination against the whites.

The leaders of the warriors, Quanah of the Kwerhar-rehnuh, Lone Wolf and Woman’s Heart of the Kiowas, Stone Calf and White Shield of the southern Cheyennes, agreed on two matters. Quanah should be paramount war chief, and the first blow should fall upon the buffalo hunters.

The tribes rode south, into the Texas Panhandle, long lines of barbaric horsemen whose passage shook the ground.

They came down on the old Bent fort at Adobe Walls just before dawn on June 27, 1874. The hide hunters had taken to using the abandoned buildings as a headquarters and rendezvous. Now, in early summer, there were only twenty-eight white hunters and one white woman in the camp, but the men had worked through the night repairing a roof beam. This saved them, for two men were outside when the Amerindian horde appeared on the ridges in the ghostly half-light. They gave the alarm before Quanah sent his riders into the attack.

The hunters made their living by marksmanship with the powerful Sharps buffalo guns. As the Comanches and their allies raced down upon Adobe Walls, the big rifles knocked down men and horses. Two Cheyennes and a Comanche who reached the enclosure were shot dead. Quanah’s own horse was killed under him; he survived only by crawling behind a rotting bison carcass for concealment.

At a distance the carbines of the Comanches were no match for the great buffalo guns in the hands of skilled marksmen. Several more warriors were killed, and the attackers drew off to the distant ridges. They charged again, but again they could not bring themselves to push the attack at close quarters, and again they were repulsed with losses.

Eeshatai sat naked in yellow war paint on his pony on a distant ridge, watching over the battle. His host could still have charged in and butchered all the hunters at any time that morning, but eighty centuries of custom and conditioning now destroyed all Eeshatai’s visions and ambitions. Surprise was lost, and the war chiefs were reluctant to press the attack against serious losses. Quickly, the Amerindians slipped from elation to manic depression. Eeshatai’s magic was flawed: the father of a Cheyenne warrior killed under the walls demanded of the prophet that if he were so bulletproof, why did he not go down and recover the body? Eeshatai sat immobile, and then, as if by fate, a Sharps ball knocked one of the warriors sitting beside Eeshatai from his horse, at a range of more than fifteen hundred yards.

The fragile alliance cracked with the prophet’s medicine. A Cheyenne struck Eeshatai in the face with his quirt. Eeshatai blamed the Cheyennes for the disaster: one had killed a skunk the day before; this had destroyed his medicine. Ancient antipathies and suspicions boiled over as the horde withdrew in confusion. Nine warriors were dead and many more wounded, some of whom would also die. They had killed three white men behind the walls.

As the great war party retreated, the hunters hugged each other, hardly able to believe their good fortune. This had been a tiny battle; but its effect was to be one of the most decisive of any fought on the plains. The alliance between Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho was shattered upon Adobe Walls. The Comanches saw the magic of the sun dance fail, and they would never invoke that medicine again. The People had been one, but briefly. As Eeshatai’s influence collapsed, they dissolved again into their habitual separatism. Some deserted the war, returning to the reservation lands.

The war against the whites was not quite over, but now it had no plan, purpose, or cohesion. Small groups of Comanches, Cheyennes, and their allies rampaged out from Adobe Walls in all directions, carrying terror and death into five states and territories. The fear and rage of the tribes fell on travelers and ranches. Stages were stopped and stations burned; small parties of hide hunters were wiped out from Colorado to Texas. Men were staked out on the prairie; white women died with butcher knives thrust into their sexual organs. The southern plains were again caught up in the horror of a widespread Indian war, which killed 190 whites in the summer months.

The hide hunting ceased. Everywhere the whites huddled around the frontier forts and towns, clamoring for protection.

This second general uprising broke the dam of public opinion as the endemic raiding in Texas had never done. As the telegraph wires hummed with report after report of verified “atrocities,” official sentiment again swung full circle. The terror and destruction destroyed the last arguments of the nineteenth-century humanitarians. Sympathy turned to exasperation and exasperation to anger. President Grant authorized the army to move immediately “to subdue all Indians who offered resistance to constituted authority.” The old “peace policy” was seen as a failure; the new peace would be imposed on military terms. All restrictions were lifted from the army in the West. Any Amerindians found off their reservation were to be considered hostile, and to be pursued. If they surrendered, they were to be considered prisoners of war. If they resisted, they were to be destroyed.

The 1874 change of policy was complete and final. The government had had a “bellyful of Indians,” as one official put it; the new concept was to end the autonomy of all the western tribes, and to force all of them onto their restricted reservations. The tribes would never again be permitted to wander off the reservations, or to make war against the whites. The southwestern raiders precipitated the change, and thus in the actions of the Comanches were caught up the fortunes and fates of all the other western peoples.

These were not really “wars,” although thousands of soldiers were employed. The campaigns of the 1870s were a mopping-up process, finishing a conflict that had begun three hundred years earlier. They were an extension of the old Jacksonian policy of Amerindian removal.

There was now almost no opposition to destruction of the Indian “barrier.” Almost all editorial opinion throughout the nation supported government policy. What discussion there was followed the lines of placing the rights of primitives against the demands and needs of civilization. In this, or in any other self-confident era, the conclusion was foreordained. Much sympathy was expressed for the aborigines, there was the sense that an era was passing, but progress was not to be denied.