Comancheria: Season 2

Rise of the Texan Ranger — el Tejano Diablo

They charged into the Mexican soldiery to kill as many as they could. These troops had seen much cruelty and understood it; but they had never seen the savagery of the Trans-Appalachian American at close range. The Texans had no bayonets, but by Mexican standards they were enormous men, towering a head higher or more. They smashed, butted, used tomahawks and knives. They had fought as paladins, each touchy of his rights and his own section of the wall. Now, they died as paladins, each with his ring of surrounding dead.

— T.R Fehrenbach, Lone Star: A History Of Texas And The Texans

The Texans burned the significance and symbolism of the pistol into the American consciousness. The revolver was only another weapon in a long train of evolution, but it replaced the German rifle as the characteristic American arm. For the Rangers quickly embellished the six-shooter with glory and even mythology. It became a symbol of courage and conquest, of American superiority. Colt’s invention killed more men in combat, probably, than any side arm since the Roman short sword.

— T.R Fehrenbach, Comanches

One by one, the children and young women were pegged out naked beside the camp fire. They were skinned, sliced, and horribly mutilated, and finally burned alive by vengeful women determined to wring the last shriek and convulsion from their agonized bodies.

When the moon set over the charred corpses, there could never again be peace between the People and the Texans, so long as any of the People stood on Texan soil.

— T.R Fehrenbach, Comanches

I sketch out three seasons of Comancheria, stitched together with bullet point summaries and extracts from T.R Fehrenbach’s superb and underrated Comanches: The History of a People. Each episode is a self-contained vignette, following a broadly chronological arc. Fehrenbach’s mesmerising prose brings to life one of the last great frontiers of history.

In season 2, we see the rise of the powerful Texan Ranger and the 2nd Cavalry. Abetted by the Colt revolver, they adopt Comanche techniques and ultimately defeat them. Around this, a brutal Anglo policy of extermination does not distinguish between Comanche and friendly tribes. The Indian Agency is horribly corrupt, and good Texans like Major Neighbors try to lead these people out of subjugation but end in tragedy.

Season 1: Rise of Comancheria

Episode 1: Chaos

Episode 2: Comanches and Apaches

Episode 3: New Spain and Villasur — 1720

Episode 4: The Massacre of San Saba — 1757

Episode 5: Don Juan Bautista de Anza and Truce — 1786

Episode 6: New Spain Terror and Decline

Episode 7: Mexico and Hell

Season 2: Comanchería y el Tejano Diablo

Episode 1: Parker’s Fort — 1834

Episode 2: Rise of the Texan Ranger — el Tejano Diablo

Episode 3: Lies and Destruction of the Cherokees — 1839

Episode 4: Council House Fight — 1840

Episode 5: The Battle of Plum Creek — 1840

Episode 6: The 2nd Cavalry — 1855

Episode 7: Lieutenant Hood - 1857

Episode 8: John S. Ford — 1858

Episode 9: Robert Neighbors — 1859

Season 3: Comancheria’s Last Stand

Episode 1: The Chivington Massacre — 1864

Episode 2: Civil War Respite — A Close Call — 1864

Episode 3: Little Buffalo and Britt Johnson — 1864

Episode 4: Colonel Pfeiffer — 1864

Episode 5: Mackenzie and his Buffalo Soldiers — 1872

Episode 6: Empire Out West

Episode 7: Eeshatai, Quanah and the Last Stand — 1874

Season 2: Comancharia and Anglo America

Episode 1. Parker’s Fort — 1834

The Parker story, one of the better known stories of the period and wonderfully told in Empire of the Summer Moon, might arc across the season. It could be a single episode, but the challenge is that unlike other episodes the tale spans decades.

The murders and abductions at Parker’s Fort

John Parker was pinned to the ground; he was scalped and his genitals ripped off. Then he was killed and further mutilated. Granny Parker was stripped and fixed to the earth with a lance driven through her flesh. Several warriors raped her while she screamed.

Abduction of Cynthia Ann Parker and life among the Comanches. Rises from captive slave to prominent and loyal Comanche wife

The rise of her son Quanah Parker as one of the last great Comanche warrior chiefs

Cynthia Ann Parker’s ultimate ‘rescue’ and sad end as a Comanche in white society

Episode 2. Rise of the Texan Ranger — El Tejano Diablo

Rise of Mirabeau Buonaparte Lamar, a hero of San Jacinto. Elected to the Texan presidency almost unanimously in 1938 on the back of bloodthirsty rhetoric to expand Texas and wipe out the Indians

Invention of the Colt revolver

The early years of Colt’s enterprise were dogged with failure. There was no civilian need for or interest in such weapons in America during those years. The United States Army did not have a cavalry arm before Americans entered the plains; the government refused to subsidize Colt’s invention. But while Colt’s enterprise sank into bankruptcy in the East, the Texan borderers immediately grasped the significance of a hand weapon that could be used from horseback and gave one man the fire power of six. Colt named his first working model the “Texas.”

The Texans burned the significance and symbolism of the pistol into the American consciousness. The revolver was only another weapon in a long train of evolution, but it replaced the German rifle as the characteristic American arm. For the Rangers quickly embellished the six-shooter with glory and even mythology. It became a symbol of courage and conquest, of American superiority. Colt’s invention killed more men in combat, probably, than any side arm since the Roman short sword. Its symbolism, unhappily, outlived its military usefulness.

The rise of the Texan Ranger

The Rangers were few and almost always outnumbered. They offset this with a violent aggressiveness, and a rapidly building legend of superiority. The Ranger captain who was called to defend the frontier against both Mexicans and Amerindians found his best defense was to attack, kill, strike fear, and dominate. Few Texas Rangers articulated this code; they lived by it. And because the Ranger situation was always perilous, the Ranger bands, unlike the farmer militias, were tightly and efficiently disciplined. There were few of the forms and courtesies of civilized military discipline, but something far more fundamental. Casual orders were obeyed implicitly. No captain asked men to do what he could not or would not do himself. He was the greatest warrior in the band, and his followers knew it

Captain Bird recruited allies in the cannablistic Tonkawas and Lipan Apaches, known enemies of the Comanches, for use as scouts

Captain John Bird rode up the Little River with fifty Rangers recruited in Austin and Fort Bend counties. Striking a band of some twenty Comanches busily hunting buffalo, he immediately attacked. The Comanches ran, and to Bird’s dismay, easily outdistanced their pursuers. Bird chased the Comanches for several miles across the open prairie before he noticed that the fleeing Indians were growing much more numerous. Alarmed, he halted the reckless pursuit and turned about in retreat, only to discover, too late, that he had now made the ultimate error in Comanche warfare.

As the Texans turned, the Comanches, now some two hundred strong, immediately wheeled after them in a turnabout pursuit. Screaming, they filled the sky with shafts. Racing for cover, Bird’s command survived only because the riders stumbled into a nearby ravine, where the riflemen could dismount and shoot from cover. Now they could stand off the swirling horse archers at long range, firing carefully, always making sure that they kept a few of their muzzle-loaders charged to repel an assault.

The Comanches could easily have wiped out the whole company, but only at a cost in blood that no Comanche chief would accept. After a desultory, angry siege, the Indians soon went back to hunting. The Rangers could thus claim that they had won the field—but it was a Pyrrhic victory. Seven Rangers were dead or dying, including Captain Bird. The bloodied company retreated to the east, and, meanwhile, the aroused Comanches rode on a rampage, carrying fire and death to a wide area of the frontier.

Episode 3. Lies and destruction of the Cherokees — 1839

The Cherokees behaved with great and tragic dignity. Their chief, Bowles, stated that he knew his people could not win, but when his request that they be allowed to harvest their current crops was refused, he asserted that the Cherokees would fight, even against his counsel. Then the tribe that had tried to live with and like white men tried to fight like white men. They mustered at arms and met the advancing Texan army in open battle, with none of the bloody raiding and indiscriminate slaughter of the normal “Indian war.” They were slaughtered themselves by superior force, and the evidence is that Bowles was needlessly murdered. After two days of violent action, the Cherokees were scattered into the pine forests, and their homes and fields were set ablaze.

The Texan commander recommended to his government that he should make a clean sweep of it while the army was assembled: that the entire “rats’ nest” in east Texas be cleaned out. The government concurred. By July 25, 1839, the corn fields and villages of all the Cherokees, Delawares, Shawnees, Caddoans, Kickapoos, Creeks, Muscogees, Seminoles, and all the other remnants from the East who had sought refuge in Texas were burned out. Some of the associated tribesmen tried to flee to Mexico; they were pursued and caught up with at the Colorado, the men killed, and the women and property brought back. A few Kickapoos went out on the plains. Most of the dispossessed peoples passed over the Red into the Indian Territory. Only two minor tribes, the Alabamas and the Coshatties, were permitted to remain, and they were moved to new and less fertile territory.

The summer campaigns of 1839 destroyed or removed virtually all the Amerindian population in the eastern half of Texas, opening up thousands of square miles for immediate exploitation. But meanwhile, the conflict in the west—from San Antonio on the south, and northeast to the Little River—remained indecisive. Bands of Rangers and Comanches swarmed along this frontier, but neither Amerindians nor Texans were able to inflict a decisive defeat on the other. Despite Lamar’s determination to push his Texan empire westward, the Comanches were a terrible barrier. The frontier could not advance in this region, and the lands lying below the Balcones Scarp were in constant peril from the Pehnahterkuh.

Lamar, whose vision ran beyond the mere extermination of Indians, moved the capital of the republic to this frontier, to the newly laid out site of Austin on the higher Colorado.

Episode 4. Council House Fight — 1940

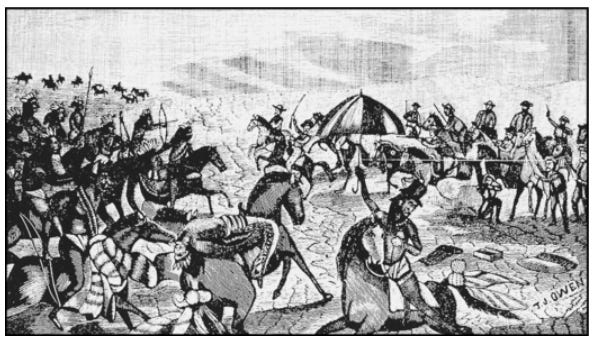

The great Comanche chiefs are invited to treaty and to return captives in San Antonio

The Comanche release one hostage which inflames the Texans

“Her head, arms, and face were full of bruises, and sores, and her nose was actually burnt off to the bone. Both nostrils were wide open and denuded of flesh.” Among the women, the girl broke into tears and said she was “utterly degraded, and could not hold up her head again.” She described the horrors she had endured. Beyond her sexual humiliations, she had been tortured terribly by the women, who had held torches to her face to make her scream. Her whole thin body bore scars from fire. To make things worse, she was an extremely intelligent girl; she had learned the Comanche tongue and had actually overheard the Comanches discussing their council strategy. She knew of some fifteen more white captives in the camp she came from.

Council House massacre of the great chiefs (a Game of Thrones Red Wedding episode)

The bands mourn their immense loss. In return, the rest of the white captives are tortured to death

One by one, the children and young women were pegged out naked beside the camp fire. They were skinned, sliced, and horribly mutilated, and finally burned alive by vengeful women determined to wring the last shriek and convulsion from their agonized bodies.

When the moon set over the charred corpses, there could never again be peace between the People and the Texans, so long as any of the People stood on Texan soil.

Episode 5. Plum Creek — 1840

A thousand Comanche horses cut across southern Texas in a crescent, a scythe of burning towns

Buffalo Hump weighed down by loot, protecting his caravan as Rangers collect militia and towns folk, every Texan who can ride and shoot, to cut them off at Plum Creek

Texans force battle at Plum Creek and massacre and route the Comanche caravan

The Comanche outriders wheeled and pranced, engaging in mounted acrobatics, shouting out their prowess and their mighty medicine, performing feats of horsemanship possible only to the people raised on horseback. Jenkins was caught up in admiration, and also struck by the grotesqueness of their appearance and actions. They trailed long red ribbons from their horses’ tails; some carried opened umbrellas, contrasting weirdly and ridiculously with their fierce, horned headdresses.

A tall warrior in a feather headdress rode out of the Comanche press and yelled insults, daring the white men to single combat… Caldwell, unimpressed by savage chivalry, told someone to shoot him. A long rifle cracked and the challenger tumbled into the dust. A throaty moan rose from the passing Comanches; this was evil medicine.

“Now, General!” Caldwell snapped. “Charge ’em!”

Huston gave the order. The Texas horsemen emptied their rifles at the Comanche throng, then, themselves shrieking like Amerindians, they spurred into the flanks of the long column. They struck down the few skirmishers on the flanks and crashed into the main body. The great horse herd was stampeded by their shots and yells.

Horses and heavily laden mules plunged forward out of control. The mule train ran into a spot of marshy ground; tired and overloaded, they piled up, unable to go farther, and the huge mass of horses crashed into them. Instantly, the whole column became a struggling screaming mass of frightened animals, and the scattered Comanche herders were caught helplessly in the press.

Episode 6. The 2nd Cavalry — 1855

The first United States cavalry regiment, by some obscure military logic officially designated the 2nd Cavalry, was authorized in March 1855. It was organized at Louisville, Kentucky, in the heart of the American horse-raising country. The regiment—“Jeff Davis’ Own”—was planned especially for operations in Texas, with great attention by the secretary himself to detail. Davis personally selected every officer for the regiment, setting aside the crippling strictures of seniority in the service; he even went outside the regular service, offering commissions to certain experienced Texas Rangers. The regiment’s commander, Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston, was the former Texas secretary of war. The senior officers of the regiment were permitted to choose their NCOs from the army at large. The ranks were largely recruited, like the horses, from the Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana countryside.

No expense was spared in equipping the 2nd Cavalry. Only the finest blooded horses were purchased by special teams. Each of the ten companies was to ride mounts of a single color: grays for A; sorrels for B and E; bays for C, D, F, and I; while G and H had browns, and Company K was roan. The troopers were furnished brass-mounted saddles and gutta-percha cartridge boxes. More important, their arms were the latest model: new breech-loading Springfield carbines and .36-caliber Colt’s Navy Model revolvers. NCOs were also issued heavy dragoon sabers, though more for show than military use. Jefferson Davis authorized officers to wear ostrich feathers in their hats. All this made the regiment a brave sight on parade, but far more to the point, it carried twelve-pounder mountain howitzers which could be disassembled for transport and it was half again as large as later cavalry units: 750 officers and men, eight hundred horses. It was unique in every respect, from its weapons to the heavy salting of southern gentlemen posted to it by the war secretary. Inevitably it was the elite outfit of the army, and even its junior subaltern was considered a lucky man and one to watch.

The forty-odd officers who served in the 2nd Cavalry during its brief five years of existence more than justified Davis’ expectations. No single regiment in American history produced so many general officers. Albert Sidney Johnston, his second in command, Robert E. Lee, Captain Edmund Kirby-Smith, and Lieutenant John Bell Hood were to become full generals in the Confederate States Army. Major William Hardee gained three stars, and Earl Van Dorn, Charles W. Field, and Fitzhugh Lee became major generals in the same service. Three more southern officers were later brigadiers. Nor was the 2nd Cavalry exclusively a southern regiment, for George H. Thomas, Kenner Gerard, George Stoneman, Jr., and Richard W. Johnson all became Union major generals. Almost all others who survived were promoted to full colonel in either service.

The southern image, however, caused the regiment’s dissolution and dimmed its luster in United States military annals, and in fact, it was an anomaly in the professional ranks. Elegant officers with black servants and ostrich-feather hats, notwithstanding their great abilities, were not in the American vein, although the 2nd Cavalry established a tradition of a kind that did not die in the Civil War. Its organization, in any event, formed the tradition for a new kind of mounted service on the frontier, and the lessons learned in twenty-five campaigns laid the groundwork for all later cavalry operations in the West. The 2nd Cavalry became the army’s school for western Indian warfare.

Episode 7. Lieutenant Hood - 1857

Lieutenant John Hood fought the bloodiest action the 2nd [Cavalry] was to win in Texas. Hood, an energetic Kentuckian, pressed out of Mason on a Comanche hunt with his scout ranging far ahead to smell out sign and prevent an ambush. Hood pushed his twenty-four soldiers for twelve brutal days of riding, before his Delaware scout cut a three-day-old pony trail. The trail led toward the Rio Grande border, over extremely rough and desolate country in which water holes ranged up to fifty miles apart, and in some of these holes the scummy water smelled so foul that men could hardly drink it. Without hesitation, Hood took up pursuit, hoping to catch the estimated twenty Comanches before they slipped into Mexico.

For four days the lieutenant pushed his gamy, bearded, and dust-covered troop south, until several of the horses were staggering with exhaustion. On July 20th, he came across a fresh camp site with still smoking embers. He was closing, but his scout reported gravely that more Comanches had come together, and that the troopers were now pursuing some fifty warriors. Here, near the headwaters of the Devil’s River, Hood took stock of his situation. He was now outnumbered, with exhausted men and jaded horses. But he could see the blue-shadowed eastern Sierra Madre just to the south, and he determined to ride at least to the Rio Grande.

Finally, the soldiers spotted Indians on a bluff overlooking the clear Devil’s River. The warriors appeared boldly, waving what appeared to be a large white sheet—a sign of truce. Hood suspected ambush, but led his troop forward into an expanse of spine-tipped yucca to meet the Indians. He was far in advance of his own line, which rode forward with cocked carbines at the ready, when the waiting Amerindians threw down their “flag” and charged at him on foot. At the same time, the thicket was set ablaze ahead of the cavalry, and some thirty mounted, painted warriors raced out toward Hood’s flanks, while others fired from the spiny thickets. A thirty-foot-high wall of flame blazed up, throwing the cavalry horses into confusion as they wheeled to meet the charge.

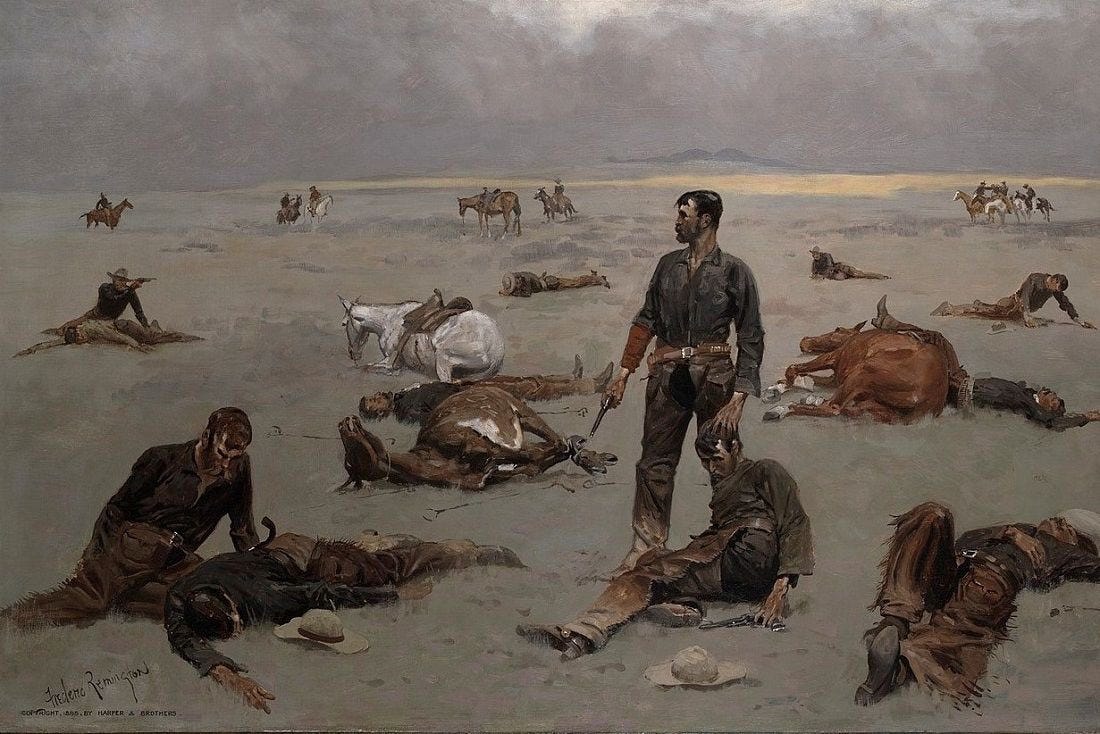

Two warriors rushed at Hood, hoping to drag him alive from his horse. But the lieutenant had learned one trick of Comanche warfare: he carried a short, double-barreled shotgun across his pommel, similar to the eight-gauge weapons the horse Indians favored. He literally blew both attackers apart at point-blank range, then wheeled and rejoined his small band of surrounded troopers.

Fifty Comanches with lances and buffalo-hide shields were already among his dissolving line, attacking both on foot and horseback. But in this melee the iron discipline of the 2nd Cavalry held, and the Colt revolvers did fearful execution. Men and horses went down, buffeted by the iron-hard shields, while Hood and his sergeant wielded their sabers. The sergeant clove one warrior to the chin with a powerful stroke. By then, Hood’s soldiers had emptied their revolvers. They could not reload on horseback. Somehow, the whole command fought its way back out of the thicket and dismounted in a tiny press to reload. The soldiers were under continuous fire, for a number of Comanche women apparently were reloading the Indian muskets and passing fresh ones to the sniping warriors.

Hood’s left hand was pinned to his bridle by an arrow. Cursing, he broke the shaft and withdrew it, wrapping his torn hand in a kerchief. At this moment, with several men and horses down and only a half dozen troopers with loaded weapons, Hood’s command could have been utterly destroyed by any determined charge. He was saved, incongruously, by the Comanche women, who as the smoke cleared saw the Indian casualties and commenced a fearsome howling. Hood later officially estimated that his men had killed eight or nine warriors, and wounded perhaps twice that number. He was too conservative, though he had had no time to count the fallen, for Comanche survivors of this engagement later verified on the reservation that there had been nearly a hundred Amerindians, and that the soldiers had killed nineteen and wounded many more. Disheartened, the Comanches failed to destroy Hood’s battered troop. They retrieved their dead and wounded and slipped away through the scrub.

Hood let them go. Two of his men were dead; he and four others seriously wounded. His horses were in poor shape, and he was without food or water. He retreated to the river and sent a rider to Val Verde County for medical assistance. The next day a relief column from the 8th Infantry out of Camp Hudson arrived to help bury the dead and resupply Hood for a march to Fort Clark.

Episode 8: John S. Ford — 1858

John S. Ford — known as “Old Rip” from his habit of writing the letters R.I.P. at the close of his casualty reports—then the most experienced Ranger officer in service, [was appointed] senior captain and supreme commander of all state forces.

Ford raised his small army of tough frontier riders, most of them experienced veterans of the frontier style of warfare. The Tonkawas and other ancient enemies of the Comanches as always were eager to serve the Texans.

Ford’s column — 102 Rangers with pack trains and at least a hundred Indian allies— left Camp Runnels on April 22, 1858. He rode directly for the Red behind a wide screen of Amerindian scouts, and crossed the river on April 29th. By May 10th, he was finding Indian sign everywhere on the Oklahoma plains: the trail marks of meat-laden Comanche travois, and a bison carcass that held two distinctive Comanche arrows. On May 11th, his careful scouts had discovered a large Comanche camp, and Ford prepared to attack.

The Rangers had not been discovered by the Amerindians. They moved differently from the army, quietly, grimly, making cold camps and without all the military jangle and furor and constant bugle signals of the cavalry. Like most old Rangers, Rip Ford fought Indian-fashion: surprise the enemy and, if possible, kill them in their lodges. His plan, however, was almost ruined by some Tonkawa allies, who, overeager, attacked and demolished a small outlying encampment of five lodges, which lay about three miles beyond the main Comanche concentration. Two Comanches escaped on horseback, crying the alarm.

Ford did not hesitate in this situation. He rode hard toward the main encampment, which spread along the shallow Canadian.

The Comanches, forewarned, failed to scatter. There were some three hundred warriors along the Canadian, and this was deep in their own country. The chiefs determined to give battle, to teach the tejanos and their despised allies a bloody lesson. Hastily painted, black for war and death, the warriors rode out in magnificent array, their great bison-horn headdresses and iron lance points glinting in the bright May sun. As Ford approached across the rolling plain, they shrieked and capered, whirling and thundering in front of the slowing Texan advance. Hundreds flowed around the Texan flanks, shouting insults, invoking powerful medicine.

Here was a scene that was to be repeated many times in the tragic Amerindian twilight on the plains: a savage horde, resplendent in their valor and barbaric finery, swirling to meet a small, sweat-stained band of bearded white riders who watched them grimly, now and then spitting tobacco juice. The Rangers, calm among their own screaming, gesticulating red allies, invoked their own rites. They cocked their rifles, and checked the seating of the red copper percussion caps on the nipples of their Colts. They wore no uniforms, but they had the discipline of combat veterans. They watched Ford, who sat staring shrewdly at the enemy, calculating the best way to break the Indians’ medicine.

And as so often, the splendid horde played into his hands. A great chief of the northern Comanches, whom the whites knew as Iron Jacket, rode in front of the Amerindian van, brandishing his long Plains lance and daring the white men to personal combat. Iron Jacket wore a burnished cuirass, left with his bones by some forgotten Spanish soldier on these plains. The overlapping iron plates had gained the chief a fearsome reputation of invulnerability in war against other Amerindians. But no Spanish armor could turn a Sharps’ rifle ball. Several Texans took aim; their guns roared, and Iron Jacket and his horse collapsed into the dust.

As Iron Jacket fell between the two hosts, Captain Ford immediately ordered the charge. Revolvers blazing, the Rangers crashed into the milling Comanche masses—riding into three times their number of horsemen. But the Texans were grimly fighting for their lives, and to wreak execution; the Indians were already half demoralized.

What should have been a desperate battle dissolved into a bloody slaughter that swirled over six miles. In this kind of melee the Comanche spears and arrows were no match for long-barreled revolvers in the hands of skilled gunmen. Again and again charging warriors were knocked from their horses by the repeating pistols. Ford kept his men pressing into the Indians, stirrup to stirrup, giving them no chance to form their deadly circle. Soon, the Comanches lost all order or cohesion, and the Rangers pursued them for seven hours, until the Texan horses were staggering. By the end of the afternoon, Ford’s Rangers had killed seventy-six warriors, seized three hundred horses, and captured eighteen women and children abandoned by the fleeing band. Ford lost two men dead.

Episode 9. Robert Neighbors — 1859

Major Robert S. Neighbors, the former Texas Indian agent was worth another regiment to the white frontier. Neighbors was appointed United States Indian Agent for Texas early in 1847, one of the most sensible appointments the Indian office ever made. Neighbors understood Comanches, due to his long service to the Republic of Texas, and beyond this, he possessed remarkable personal qualities. He was without greed, personal ambition, or arrogance, neither a true political appointee nor part of the federal bureaucracy, and possessed of infinite patience, tact, and wisdom. Neighbors had no illusions about the Indians, but he met and sat with them as equals, and spoke without hypocrisy. The Pehnahterkuh came to respect and even like him as they did few white men. For some two years, Major Neighbors kept a sort of peace single-handedly, through the force of his personality, and through some extremely effective personal relationships with the Pehnahterkuh civil chiefs.

The corruption of the [Indian] office, admittedly heightened in the American consciousness by the telling arguments of soldiers in the West, became proverbial. Many of the same agents who cried loudest about military operations against Indians saw no shame in robbing them. Honest Indian agents were unpopular in the service. Neighbors was vastly respected but liked by only a few of his white colleagues, and, in fact, he was dismissed in the politics of the reorganization of the office in 1849.

Neighbors dismisses accusations against reservation Indians of crimes they don’t commit. Ford investigates and dismisses charges.

After years of failed policy and official corruption, Neighbors knew his charge could no longer stay in Texas. From Fehrenbach’s Lone Star:

Escorted by soldiers and Rangers, the thousand reserve Indians marched north, leaving gardens, corn, and cattle behind. Their few belongings were carried in Army wagons. It was a long, dry, terrible trek, and some of the U.S. troopers who guarded it described the passage in bitter terms. On September 1, Agent Neighbors—who had never backed down to any man, who was respected by every official in the state, not one of whom would publicly acknowledge it—forded the Red with his pitiable crew, and turned them over to another Indian agent in a strange land. There is no record of how he said goodbye to the people who had put their faith in him. But that same night he wrote his wife in Texas:

I have this day crossed all the Indians out of the heathen land of Texas and am now out of the land of the Philistines.

If you want to have a full description of our Exodus out of Texas—Read the 'Bible' where the children of Israel crossed the Red Sea. We have had about the same show, only our enemies did not follow us. . .

These were the last lines Robert Neighbors ever wrote. He rode back into the land of the Philistines to make his final report. At Fort Belknap, while he was talking to Pat Murphy, Murphy's brother-in-law, Ed Cornett, whom Neighbors had never met, shot the Indian agent in the back.

It was 'not possible' to bring Cornett to trial. But on the other hand, it was not permissible on the frontier to shoot a white man, even an Indian-lover, in the back. John Cochran and Ben R. Milam got together some 'Minute Men.' This group convened a 'court' in April 1860, months after the murder, and went after Cornett. He 'made fight' on Salt Creek, as one of the members of this posse said, and all accounts agree that Ed Cornett was brought to justice without benefit of judge or jury.

I want to watch this so bad...

Tremendous thank you