Hitler's Soviet delusion

It was never even close

Every Russian soldier has to be shot dead twice, and even then he has to be pushed to make him fall.

— Frederick the Great

The effect of climate in Russia is to make things impassable in the mud of spring and autumn, unbearable in the heat of summer and impossible in the depths of winter. Climate in Russia is a series of natural disasters.

— General von Greiffenburg, Chief of Staff to 12th Army

I am refraining from publishing big maps of Russia. The huge areas involved can only frighten our people.

— Joseph Goebbels

The economic foundation of Operation Barbarossa remains one of the most tenuous in military history.

— David Stahel, Kiev 1941

Although the combined Wehrmacht and Waffen SS numbers totaled approximately 7 million in 1941 (of which about 3 million were in the East), there were virtually no reserves… Beyond those divisions, no more than 321,000 men on active duty were available as trained replacements. This pool was exhausted within the first few months of the Soviet war, after which there were no additional replacements until the following year.

By contrast, in addition to the 5 million Soviet servicemen on duty when the Germans attacked, there were 14 million trained reservists.

— David Glantz & Jonathan House, When Titans Clashed

[I]t stands out more and more clearly that we underestimated the Russian colossus… At the start of the war we reckoned with 200 enemy divisions. Now we already count 360.

— General Franz Halder, in his diary 11 Aug 1941

Even Hitler allegedly remarked that, had he known that Heinz Guderian’s prewar figures for Soviet tank strength were so accurate, he might not have started the war.

— David Glantz & Jonathan House, When Titans Clashed

The first communists were Adam and Eve. They had no clothes to wear, had to steal apples for food, could not escape from the place in which they lived and still they thought that they were in paradise.

— Joke by German soldier

“We have to win this war. We must not lose our courage. If others win the war, and if they do to us only a fraction of what we have done in the occupied territories, there won’t be a single German left in a few weeks.” It became so quiet in that carriage that one could have heard a pin drop.

— Antony Beevor, Berlin: The Downfall 1945

An escaped British prisoner of war, a fighter pilot, picked up by a unit of the 1st Ukrainian Front and taken along, saw a young SS soldier forced to play a piano for his Russian captors. They made it clear in sign language that he would be executed the moment he stopped. He managed to play for sixteen hours before he collapsed sobbing on the keyboard. They slapped him on the back, then dragged him out and shot him.

— Antony Beevor, Berlin: The Downfall 1945

Thinking about invading Russia fills me with anxiety. Can you imagine being the first German soldier to see German tank shells bounce off Soviet T34 and KV tank armour? Surprise!

German generals flustered by maps marking roads where there were swamps, and industrial areas where there were fields. What roads they had were barely passable dirt tracks. Intermittent summer rains turned these tracks to mud then baked clay that ground engines to dust. Bridges needed reinforcing before armour could cross. Limited German rolling stock didn’t fit Soviet gauges. Surprise!

Endless waves of bellowing Soviet infantry in suicidal attacks terrified the Germans. Their diaries are filled with shock at the ferocity of Soviet resistance. Nothing like the western front. Soviets played dead or feigned surrender only to kill. They fought to the death.

Surprise.

The enormous numerical disparity, dismally underestimated by the Germans, probably doomed the German offensive from the start. Add to that an already stretched and depleted economic base totally inadequate to a war of attrition; superior Soviet tanks and arms production; vast distances that left Panzer spearheads isolated from their infantry; the impossible task of supplying a patchwork of vehicles and parts, worsened by French and Czech requisitions;1 tough terrain that bled fuel and engines and tyres at a time when Germany had none to spare; a porous front that filled forests with Soviet partisan armies waging relentless guerilla campaigns in the rear.

And that’s before the Russian winter — which in 1941 was one of the harshest in decades.

On 22 June 1941 Germany attacked its Soviet ally with the largest army ever assembled.

Over 3.5 million Axis personnel, ~3,400 tanks, and ~2,700 Luftwaffe aircraft on a front 2,900 km wide. Hundreds of thousands of motor vehicles and ~700,000 horses.

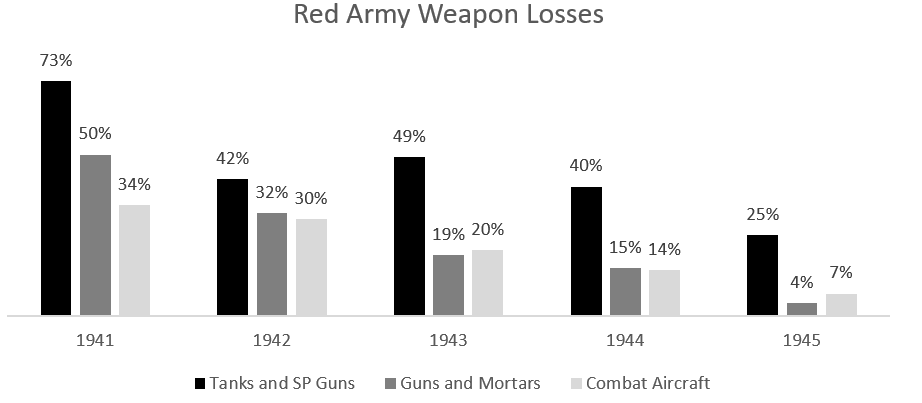

By December 1941 the Soviets had lost ~21,000 aircraft, many in the first weeks with many thousands on the ground. Tank losses in 1941 alone were ~20,500. In just the first 8 months, the Germans captured ~3.4 million Soviet soldiers; ~2 million were dead by February 1942 from starvation, exposure, and shootings. Many of these were taken in sweeping encirclements, where the Germans captured up to ~670k prisoners at a time. The losses were staggering, beyond anything the world had ever seen.

On 4 October 1941, Hitler was elated and told an audience the Soviet enemy was beaten “and would never rise again.”

Stalin is often blamed for the disastrous opening of Germany’s offensive against the Soviet Union. Stalin had ignored at least 84 warnings from intelligence sources, according to Richard Overy in Russia’s War.

Why was Stalin so blind? The Soviet Union had the largest intelligence network in the world. Why did Stalin disregard it entirely? He was a man with an almost congenital distrust of others. Why did he apparently trust Hitler, most artful of statesmen? There is no easy answer. Stalin based his calculations partly on rationality. He argued that to invade the Soviet Union with its vast army and overstretched frontier would require a numerical advantage of two to one for the attacker. This Hitler did not have… Stalin was no military genius, but he could see no sense in Hitler striking east in June with only a few weeks of combat weather remaining… He projected onto Hitler his own sense of what was possible.

Actually, Stalin’s sense of what was possible for Hitler turned out to be spot on. He was correct to disbelieve Hitler could possibly think to defeat the Soviet Union with the forces he had. Surely Hitler would be mad to open a second front in his European war, with Britain unsubdued. And surely not against such a giant — if still ill-prepared — foe as the Soviet Union. And certainly not one that over the preceding 12 months had shipped 2 million barrels of oil, manganese and other critical materials to Germany as an ally. But states don’t always act rationally! And Hitler did the mad thing. The war was a catastrophe for the USSR as measured in blood, but it was an existential failure for Hitler, precipitating his own defeat and suicide, and the rape and occupation by the Soviets of swathes of Germany for another half century.

So resilient was the Soviet Union that by 1945 it invaded Germany with an army larger than it had started with in 1941, larger than the one that had attacked it, and significantly more motorised and modern than the Wehrmacht of a few years before.2

In its massive offensive, Germany had only a few more divisions than in France a year earlier. There they had gained a territory of around 50,000 square miles. In Russia they were deployed to over a million square miles. It was an exercise born of hubris and profound underestimation of the enemy.

The traditional narrative of the Eastern Front is a little bonkers. Stalin wasn’t so mad to consider a German invasion utterly delusional, because it was utterly delusional. Defeat for the Soviet Union did not balance on the edge of a knife at Stalingrad; it was just as far as Germany got, stretching its men and supplies to impressive lengths. And there it met an industrial colossus deep within its own lands, close to its own industrial bases, and so staggeringly beyond the German generals’ anticipated strengths that it was able to muster a surprise million strong army to encircle and destroy Germany’s main army there. Through the war, the Soviet Union could afford to lose four men for every German and still conjure an army equivalent to what the Germans attacked her in the first place.

One reason for the Soviet Union’s ability to replenish its manpower was its demographics. The Soviet Union had a far younger population than Germany. In 1941, ~45% of Soviets were under twenty, compared with ~33% in Germany. This demographic advantage, combined with the USSR’s larger size, meant that even with vast swathes of territory under German occupation, the Red Army could throw ~2 million new recruits into the grinder each year.

Stalingrad was a brutal battle that could have gone either way, but it wouldn’t have mattered much if the Germans had won it — it was long over for them. Germany lost when it attacked and failed to defeat the Soviet Union in its opening gambit. The Germans simply did not have the economic base to fight a protracted war against the Soviet Union.

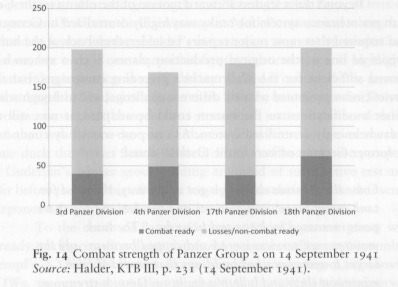

Could the Soviet Union have lost? At the time, this was a real fear. The Germans, the Soviets, and the Western powers all thought so. Hence American largesse in supplying the Soviet Union through Lend Lease. In hindsight, it’s hard to see how. Germany had dramatically underestimated Soviet forces, industrial output, and the severe constraints of Soviet climate and geography. They had dramatically overestimated their own ability to seize and hold vast lands of enemies in a mutual war of annihilation. They had to rely on Soviet political collapse or capitulation, as in France. The Germans even had over a million Soviet citizens fighting for them, a legacy of Stalinist brutality in Ukraine and the Baltics. German massacres and brutality against the local populations made things even harder for themselves.3 It is very difficult to see the circumstances required for Germany to have defeated the Soviets. The Soviets blundered so spectacularly as it was. The Germans fought as well as they could; the flower of their command and officer corps won vast early victories but were left buried across Russia in 1941, leaving a greener, less confident, less mobile force by 1943. But even by the failed attack against Moscow in late 1941 the strain on the Wehrmacht was apparent: only 75% of troops could be transported for the attack because so many trucks were out of commission and half of all tanks were inoperable for lack of parts.

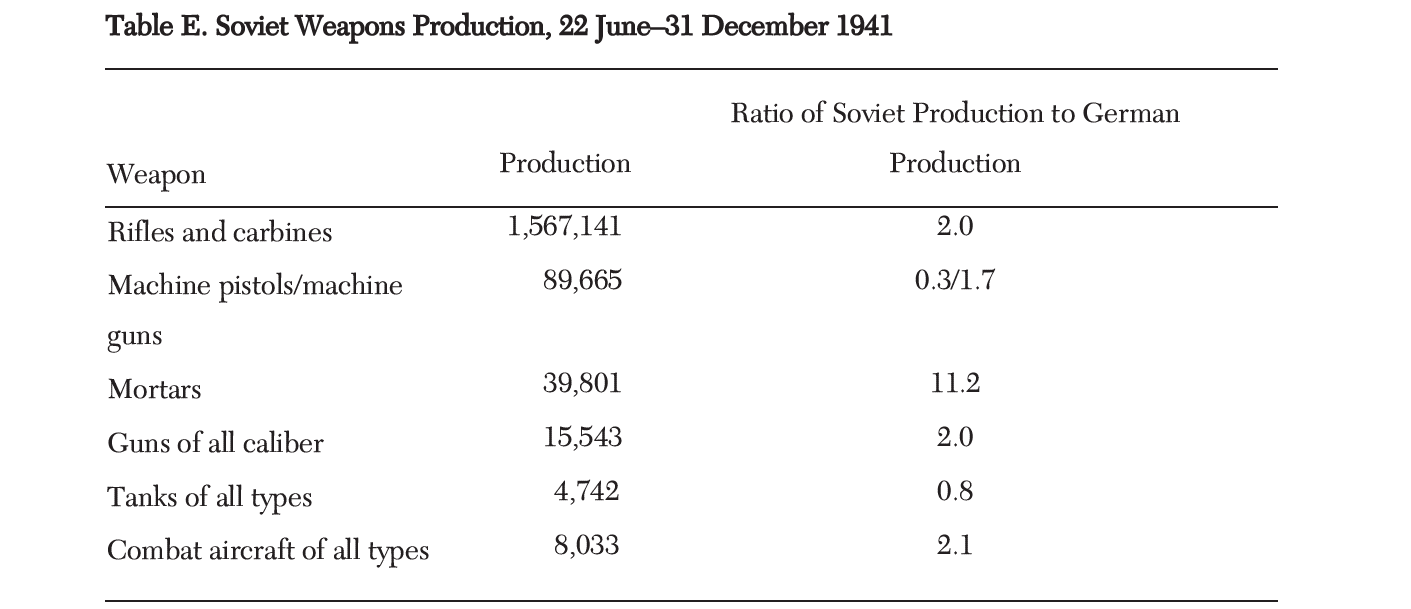

Now, nothing in the affairs of men is inevitable. The Soviet Union’s remarkable lift-and-shift east of its industrial base was essential to its victory. But to give a sense of how little a dent the largest military onslaught in history had on the Soviet Union’s industrial capacity: the Soviet Union tripled production of key armaments in the second half of 1941 compared to its first half.4 And in 1941 the Soviet Union produced more tanks than Germany. This is all while Germany thought it had crippled the Soviet Union and that it was on the verge of collapse.

Perhaps it was not inevitable that the Soviet peasant and fighter would make such a ferocious opponent (although Napoleon and Frederick the Great found the same). Perhaps political defeat was on the cards. Why couldn’t the Soviet Union just be another France? You can taste the Germans’ sense of inevitability about it: if their ancient Franco enemy, the titan of Europe, crumbled in six weeks, surely the subhuman, Jew-inflected backward Slavs of the east were no better. But the Soviet Union was no France, the Soviet muzhik no Frenchling, and the vast expanse of the steppe no Champs-Élysées.

Under the fierce onslaught of the German surprise attack, the Soviets learned. They learned from the Germans and from their own defeats. And just like when America roared into industrial might after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, so the Soviets improved supply lines and brought their industrial capacity to bear. The German surprise offensive was powerful, but it destroyed largely older and obsolete tanks and planes. These were replaced by newer models. The air force was reformed, concentrated into air armies rather than disparate army support functions. Radio and communications were introduced into air and armoured vehicles (thanks in large part to Lend Lease). Airfields were camouflaged, following the disastrous mauling delivered by the Luftwaffe at the opening of the war. The already formidable T34 tank was upgraded, and self-propelled field artillery introduced. In 1941 they lost 6 or 7 tanks for every German tank. By the autumn of 1944 they reduced that ratio to 1:1.

Stalin and Zhukov seem to have privately admitted that they could not have won the war without American Lend Lease support (per Richard Overy). The numbers don’t seem to bear this out. Lend Lease supplied astonishing amounts of certain key goods — a third of Soviet vehicles, over half its food, copper, rubber, explosives, aircraft fuel, railways and locomotives. But most of these goods were delivered after 1943 when the Germans were already stretched much too thin. But easy, again, to say in hindsight. Perhaps there is some special combination of allied goods withheld, earlier total-war German mobilisation,5 and deeper Soviet incompetence that would have led to total Soviet industrial collapse. But the Soviets were already so incompetent and the Germans so effective relative to what they had, it’s hard to see how.

As one historian noted, if the Allies hadn’t opened a second front maybe Germany’s defeat would have taken 12-18 months longer, costing more Soviet blood but ending at the Atlantic instead. The Allies helped a lot — Lend Lease was a boon to the Soviets, the invasion of Normandy a big diversion of resources, and even the war in North Africa absorbed vital panzer divisions and aircraft. But in the end, the Soviets probably didn’t need any of these to defeat Germany.

The popular narratives of Germany’s defeat in the Soviet Union — they invaded too close to winter and Hitler meddled too much in operations — are basically wrong. Every season is the wrong season to invade Russia. As one German general said, Russian weather is a series of natural disasters. Winter froze and starved under-equipped soldiers, but spring and autumn rains turned the roads into impassable mud. Summer was no reprieve: heat, flies, and typhus, with dust that choked engines and burned through oil faster than Soviet shells. As for Hitler’s interference, it wasn’t always disastrous: his stubbornness famously helped at times, including in victory over France and in the campaign against Moscow. His fatal order to hold at Stalingrad certainly doomed the Sixth Army to encirclement and annihilation — but by then, Germany had already lost the war.

Germany’s timing was actually excellent. Germany was in peak strength and the Soviet Union was mid-transition institutionally and industrially, and reeling from military purges. Officers were taken straight from prison to battle field commands (Rokossovsky, one of the most brilliant Soviet generals, was tortured during the purges and was made Marshal in 1944). Germany had to defeat the Soviet Union in its opening blows: it simply did not have the economic base or the manpower to sustain any other kind of prolonged war. And it had an excellent go of it — it’s hard to imagine it having gone any better. But it was not enough, because the entire enterprise was utter lunacy. So despite the Soviets being caught completely off guard and unprepared, and despite the Germans being at their very military peak, and despite the Germans mauling the Soviet Union to unprecedented and catastrophic levels of bloodshed — it was ultimately a complete German disaster.

Maybe Hitler had to attack regardless: the Soviet Union was a long term ideological threat, they were competing for the same sphere of influence, and Germany was dependent on it for certain critical supplies. Did Hitler choose the best of a bad bunch of options? Was invading the Soviet Union an unavoidable strategic imperative? Well, if your strategic imperative leads you to existential ruin, of what good is your strategy? It’s a little ‘if my grandma had wheels she’d be a bike’: if the Nazi regime wasn’t committed to murderous expansion, it may have found an alternate path. Yet the regime careened into the Russian abyss. If I may be bold enough to suggest: perhaps Nazism was a bad idea? Surely it could not have gone worse for Germany than what happened. So no, launching the war against the Soviet Union was not inevitable, and if it was inevitable within the logic of Nazi Germany, that’s an indictment of it, and not an excuse.

Hitler and his vaunted Junker generals drove their engine of destruction impressively far considering how wildly outgunned they were. But it wasn’t nearly enough. The invasion of the Soviet Union was not a calculated risk, but perhaps the greatest blunder in military history, born of hubris and a fetid ideology.

Germany had to supply around a million individual parts. The Soviets narrowed their product range, focusing on simpler mass production runs.

2.5 million personnel, 6,250 tanks/assault guns, 41,600 guns & mortars, ~7,500 aircraft, ~95,000 motor vehicles (many US made and supplied under Lend Lease).

German brutality radicalised the Red Army against them also. Instances of shooting captured Germans out of hand compared with sparing Italian troops, who were known to be non-exterminationist in their conduct, is an example of this effect. An anecdote about German brutality and its consequences from On a Knife’s Edge:

To an extent, many German officers were condemned whatever they did. Ewald von Kleist, whose troops were stranded in the Caucasus while Balck was struggling to hold the Chir front, had been forcibly retired from the army before the war because of his strong royalist views and his unhidden dislike of the Nazis…

Unlike many of his contemporaries who later questionably claimed – like Manstein – that they had opposed the brutal orders regarding commissars and others, Kleist undoubtedly treated the Russians with kindness, commenting in September 1942: “These vast spaces depress me. And these vast hordes of people! We’re lost if we don’t win them over.”

Ignoring the directives from Hitler, Kleist actively worked to recruit men from the Caucasus region and succeeded in raising several hundred thousand auxiliary troops, despite the protests of individuals like Erich Koch, the Reichskommissar for the Ukraine. He personally told SS and other officials that in his area of command he would not tolerate the excesses that were widespread elsewhere.

However, his conduct did not save him from the wrath of the victorious Allies. After the war, the Soviet Union – which imprisoned and executed many Germans for their brutal misconduct on the Eastern Front – convicted Kleist of the crime of “alienating through mildness and kindness the population of the Soviet Union.” He died in captivity in 1954.”

Per David Stahel’s Kiev 1941: Hitler’s Battle for Supremacy in the East:

The monthly averages of the first six months equaled 1,000 aircraft, 300 tanks and 4,000 guns and mortars, which jumped in the second half of the year to 3,300 aircraft, 800 tanks and 12,000 guns and mortars.

Germany introduced rationing and mobilised its female and foreign workforce only in 1942 after the Eastern Front had already turned into a war of attrition. It was much easier for Germans to support distant wars when they were victorious and not costly on the home front.

I find alot of this discourse very tiresome. The determinists which make the variations of cases the Nazis were inevitably going to lose (British historians in my experience are the worst about this for reasons I do not understand) and pretend the war was not a close run thing really have to reckon with how much the German army overperforms for the entire war. I'd recommend you look into the work of one Colonel trevor Dupey who is the father of modern quantitative military analysis, McMeekin also makes a very compelling summary case for how bad the Soviet military situation was in by late 1942 in Stalins War, and Kotkin also has some some interesting statements on how close the Soviet industrial base came to collapse in 1941-42 but I forget which book it was in. Glantz who you cite in this has done very good work in correcting how incompetent Soviet high command has been viewed in WW2 but this makes the German accomplishment more impressive not less.

To address the substance of the post even with all the structural problems with the German war economy and retarded blunders Hitler and his commander at made at various points you rightly point out they somehow make it within TWENTY MILES of the Caspian Sea. If the front line froze at high point of Case Blue and they fail to advance any further which is not that hard to imagine not much has to change for Uranus to turn out like Mars, its extremely feasible for Germans to win a war of attrition given the disproportionate Soviet casualties experienced through all stages of the war. By late 1943 the Red Army was extremely dependent on conscripting more or less every man of fighting age in territory they recaptured and even then by the end of the war they were pretty close to literally running out of men of fighting age in sectors non-critical to the war effort. As you mention yourself the Soviet leadership were vary conscious of how close to catastrophe they came.

The primary reason I care about these arguments and Determinism generally is it gives people the impression human decision making and therefore human capitol generally dont really matter that much and that attitude is one of causes of our leadership class becoming noticeably less capable. Say what you will of the FDR admin being completely infiltrated by Communist spies but those people knew how to run complex systems, they could build things, our current leadership class has repeatedly shown they cannot.

Ah, the old "When was Operation Barbarossa cooked?" debate. The answers range from doomed from the start to Kursk. I've heard people argue later than Kursk, but I don't think that case is minimally serious. I tend to agree with you. The Axis never really had a chance, but even if there were one it was long gone when they couldn't take Moscow in 1941. Hitler thought the summer of 1941 was as good as it was ever going to get for their chance of victory. It probably was, but the best chance still wasn't anywhere near good enough.