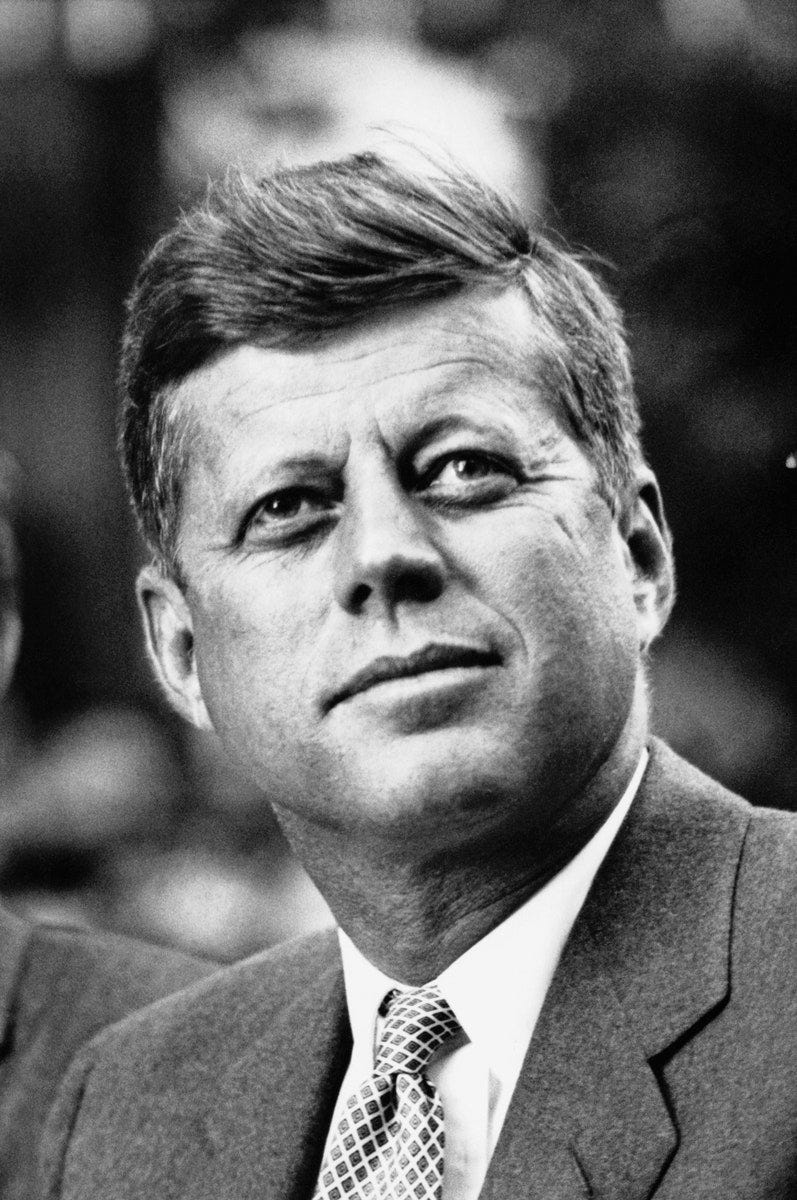

JFK

The Hero Prince of Camelot and the "Riverboat"

I’ve been as soaked in the background mythology of JFK and Camelot as anyone else over the last half century. I didn’t quite realise just how little I knew about the man until I read The Passage of Power, the fourth volume of Robert Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson. My impression was that of a foppish boy king, a playboy celebrity President, vaguely incompetent as he presided of the Bay of Pigs invasion — a “perfect failure”, in the words of historian Theodore Draper.

And it seems that senatorial peers of JFK thought so too:

Who would take Kennedy seriously anyway? Johnson said. He knew him from the Senate, and he was little more than a joke there: a rich man’s son, a “playboy,” and, he said, “sickly” to boot, always away from Washington because of some illness or other, and never accomplishing anything when he was present.

Boy was I wrong. And so was Johnson.

There’s a reason why Caro’s epic (and as yet unfinished) biography of Lyndon B. Johnson is so lauded. It’s not just the vivid vignettes of American ages past. Nor the character studies of minor American figures — the noble Coke Stevenson and his idyllic love, the Roman-eagle-visaged Dick Russell of the Georgia Russells, the apple-cheeked Harry Bird of the Virginia Birds, or LBJ’s own wife Lady Bird; stolid, hyper-competent and above all, loyal. Nor is it just the plethora of minor characters with their sumptuous asides. Characters like Abe Fortas, “a short, silent young Jewish lawyer from Memphis with olive skin, large, liquid eyes and “the most brilliant legal mind ever to come out of the Yale Law School,”” the perfectly named Julius Caius Caesar Edelstein, the patron George Parr and his burly pistoleros, or the once mentioned Frank C. Oltorf, “a considerable connoisseur of women”.

Nor is it just the immaculate detail. Caro moved with his wife to the Texas Hill Country, a hard land against which generations of Johnsons and Buntons had toiled and lost, to crack open the residents’ stories. And from them Caro drew the back-bending lives of its women — lives of medieval serfdom — before LBJ emancipated them with electricity. Caro brims with satisfaction when he paints a historical consensus — of JFK’s relationship with LBJ, or the goings-on of a campaign, or a dimly lit senatorial room — and undermines it with his own painstaking work. It took this kind of effort to dig up what LBJ was like behind closed doors, away from cameras and ambition’s path. How he uplifted his poor Mexican students in a desolate border town school and helped the school’s janitor learn English before and after classes each day on the school steps with a textbook he bought for him himself.

Maybe more than anything, what makes Caro’s work thrum is his storytelling. His tale emerges from the detailed character studies and the drum beat of history. Maybe if you just care enough — and Caro’s heart bleeds through every word — then you will pull on enough threads to weave a story. His whole life LBJ worked harder than anyone else — “if you do everything, you’ll win” — and wanted to win with an unrivalled desperation. In this Caro mirrors him. Caro does everything — pulls every thread — to weave his tale.

And how much stranger truth can be than fiction.

Is there a character in literature that burns as deeply as LBJ to win? Is there a more heroic, glamourous opposite to be found than in JFK? A rich boy who, sure, was helped along by his rich dad, but whose true power came from his grit and his charisma? His ability to disarm? Disarm a man, a room, a nation? Where LBJ shied about from danger, JFK leaned in, demanding to be sent to war and saving his capsized and stranded crew with a message etched on a coconut. Where LBJ deployed his parochial Texan manner — the “Riverboat” JFK called him as though a character out of Mark Twain — and bent the world around his indominable will, JFK cut to the heart of a nation with a steely determination and an east coast elegance. But it was not all contrasts for these arch-rivals. Both men suffered tremendous pain and illness through their campaigns, both risking death and literally collapsing at times in their doggedness.

But the denouement of Caro’s JFK tale must be what we know the whole time is coming: JFK’s assassination and the ascension of LBJ to the presidency. Yet even as we know this, we are led to that gunshot as if for the first time. Because moments before the gunshot, LBJ was not soaking in its anticipation. He was soaking in humiliation. Humiliation and trepidation. This giant of a man with giant ears and long arms and a big nose and awkward gait, who had stitched up elections and states and ultimately the Senate — the most fiercely independent body in the US government — who had wooed and won over political giants like FDR, Sam Rayburn and Dick Russell, was now Vice President. And after a lifetime of accumulating power, this unprecedent political genius — this reader of men, “the greatest salesman one on one who ever lived” — was powerless. And was stewing in insignificance behind a boy prince President. The object of ridicule on Capitol Hill. Facing the barbs he so desperately feared all his life, the barbs he saw his own father face: the barbs of humiliation. And more than that. At the very moment LBJ was being driven behind the President’s car in Dallas, reams of reporters were uncovering his illicit gains and weighing whether to publish an interim piece on LBJ corruption for the next print or wait to do a longer series. And more again: thousands of miles away a witness with receipts was spilling the beans to the Senate Rules Committee. Caro paces this thriller masterfully. We have seen this giant of a man spend a lifetime accumulating power and fall into the Vice Presidency hole — itself a political invention too silly and strange for fiction, appropriate only for parody (like Veep). And right on the cusp of political oblivion the sword of Damocles above LBJ is shot through with a single rifle shot that blew the brains out of JFK and had his wife sprawl herself across his limp and bloodied body. And from that hole LBJ rises, clutching a shocking and macabre victory thrust upon him from the jaws of defeat. The witness before the Senate Rules Committee literally grabs for his receipts and recedes into history. The reporters on his case decide to give him a chance — besides, there won’t be room for their report amidst all the JFK news. LBJ had handed back the power he had so uniquely forged in the US Senate to become Vice President — the most powerless role in government — reckoning that was his best shot at the presidency. Odds of one in four or five, he had figured. That was the base rate, the outside view of how often Vice Presidents had ascended the throne he had yearned for all his life. And now that time had come, his dawn had arrived at precisely his darkest hour.

And what of this murdered prince? Perhaps the most famous murder in history, the first assassination beamed across television. It’s impossible not to feel the sob in the spine as this man — who’s by now charmed us so thoroughly in Caro’s telling — disappears. The shot at the car ahead, from Vice President Johnson’s perspective, is heart-wrenching as the boy-hero we feel we’ve just got to know is jerked out of view forever.

I want to share JFK’s story below. I extract the better part of Caro’s chapter on his heroic backstory (edited for brevity). This chapter does not capture JFK’s charm so much as his grit. Less his elegance and more his heroism. Because without his grit and heroism, his charm and elegance would be foppish and dilettante. With them, his charm and elegance become legendary.

One thing that is lost in the background mythology of the man was his near-deadly and always-painful ailments. It’s remarkable that the twin giants of American leadership in the 20th century — FDR and JFK — were crippled or close-to. The modern sub-strand of wokeism concerned with “ableism” looks very different and is strangely discordant with this reality. We do not get this muscular version of disability — breathtaking perseverance and strength in the face of adversity — but rather a neurotic, feminised, victimhood obsessed version.1

The extract below does not delve into JFK’s philandering, his insatiable appetites, the ways in which he turned the White House into a bordello. Caro mentions a few mistresses only as they coincide with the story of LBJ. There’s the “scintillating” Georgian Helen Chavchavadze who Johnson knocked over dancing in one of his moments of humiliation — “He lay on her like a lox”. There is the ‘hostess’ of an elite club frequented by politicians. JFK is off “cruising in the Mediterranean with two of his fellow pleasure-seekers” as his wife miscarries. His brother Bobby is by her side and arranged for the infant’s burial and her comfort. Bobby had driven through the night to be by his brother’s wife’s side. JFK “did not rush back”. I will kvetch separately on LBJ’s women, but this appetite is something he shared with JFK. Both men no doubt attracted women by virtue of their stations, as wealthy men, as President and Vice President. By virtue of their power. (I wrote about the power of charisma and Hitler’s female admirers here). But their personal charisma took different forms. LBJ’s charisma lay in his intensity. He had to win, just had to have whatever he was after. His courting of his wife might now be called love-bombing. The same will to power that bent men and the universe around him drew in women. JFK’s charisma was different. Where LBJ bombed, JFK disarmed. Where LBJ bellowed, JFK quipped. LBJ grabbed men by the lapel and pressed them into couches and into submission. JFK smiled and understood. LBJ would run the hem of your dress up with his large hands. JFK just glided on through. Power comes in many forms.

The extract below is long. Initially I only wanted to share JFK’s heroics in the Navy (by God, message on a coconut!). But the preamble and then his persistence and near-death through his campaigning were too on point, and I didn’t have the heart to cut more. Enjoy!

[T]he attraction of his “boyish, well-bred emaciation” for women of all ages (“every woman who met Kennedy wanted either to mother him or marry him,” the Saturday Evening Post reported) was so intense it might have been humorous were it not later to become a central fact of American political life, and indeed to play a role in altering America’s political landscape.

[A]s a senator, Lyndon Johnson said, Jack Kennedy was “weak and pallid—a scrawny man with a bad back, a weak and indecisive politician, a nice man, a gentle man, but not a man’s man.”

Hungry and thirsty, his men started to despair, but Kennedy never stopped trying to get them rescued. The cuts on his bare feet from the sharp-edged coral reefs were so festered and swollen that his feet “looked like small balloons”… Kennedy scratched a message to his squadron on a coconut shell for the natives to take away with them, and two days later, on the sixth day of their ordeal, his note having been delivered, they were rescued.

— Robert Caro, The Passage of Power

The Rich Man’s Son

LYNDON JOHNSON MIGHT have been excused for misreading John Kennedy. A lot of people in Washington had misread him. When he arrived on Capitol Hill as a newly elected representative from Boston in January, 1947, he was twenty-nine years old, but so thin, and with such a mop of tousled hair falling over his forehead, that he appeared even younger. He was the son of a rich man, a very rich man—a legendary figure in American finance: Joseph P. Kennedy, who had made millions in the stock market on its way up during the Roaring Twenties, and then, selling short on the eve of the 1929 Crash, had made millions more on its way down; who had then turned from amassing wealth to regulating it, as Franklin D. Roosevelt’s dynamic chairman of the new Securities and Exchange Commission; who had been FDR’s ambassador to the Court of St. James’s; who had then, through investments in real estate, and movies (and, some incorrectly said, through bootlegging), turned millions into tens and then hundreds of millions—into one of America’s great fortunes, into wealth that seemed almost limitless, and into influence, in Hollywood, in the media, that seemed to match. Everyone in Washington seemed to know that the ambassador had given Jack—along with each of his other eight children—his own million-dollar trust fund, as everyone in Washington seemed to know that the ambassador had bought Jack his seat in Congress with huge campaign expenditures. And for some years after Jack Kennedy’s arrival on Capitol Hill, that was all he seemed to be: a rich man’s son.

His appearance reinforced the stereotype. He was not only thin—barely 140 pounds on a six-foot frame—but, in the words of one House colleague, “frail, hollow-looking,” and below his tousled hair was a broad, gleaming, boyish smile; when a crusty Irish lobbyist, testifying before one of Jack’s committees, repeatedly addressed him as “laddie,” he did so not out of disrespect, but, as James MacGregor Burns wrote, because “it was just the natural way to talk to someone who seemed more like a college freshman than a member of Congress”; one of Kennedy’s fellow members, in fact, once asked him to bring him a copy of a bill, under the impression that he was a page. The college-boy image was reinforced by the fact that he dressed like one, not infrequently appearing on the House floor in crumpled khaki pants and an old seersucker jacket, with his shirttail hanging out below it; sometimes he wore sneakers and a sweater to work. And when he wore a suit, so loosely did it hang from his “wide, but frail-looking shoulders” that he looked, in one description, like “a little boy dressed up in his father’s clothes.” And reinforcing the image was his attitude: his secretary, Mary Davis, a woman who had worked for other congressmen, liked Kennedy “very much” when she met him: “He had just come back from the war and wasn’t in topnotch physical shape. He was such a skinny kid! He had malaria, or yellow jaundice, or whatever, and his back problem”; his suits, she says, were just “hanging from his frame.” But she grew annoyed by his cavalier attitude toward his job: by the way he would toss a football around his office with friends; once when she complained about his absences when there was work to be done, he said, “Mary, you’ll just have to work a little harder.” “He was rather lackadaisical,” she says. “He didn’t know the first thing about what he was doing.… He never did involve himself in the workings of the office.” For constituents’ problems, he had little patience: once, having set aside two days to see them in his Boston office, he gave up after the first day, telling another secretary, “Oh, Grace, I can’t do it. You’ll have to call them off.” His service in World War II had included a highly publicized exploit in the Pacific—a long article had been written in The New Yorker about it—but in 1947 there were scores of men in Congress with celebrated war records, and some of those records wouldn’t stand close scrutiny: the new senator from Wisconsin, for example, liked to be known as (and sometimes referred to himself as) “Tail-Gunner Joe” McCarthy and had received the Distinguished Service Medal, although he had never been a tail (or any other variety of) gunner but rather an intelligence officer whose primary duty during the war had been to sit at a desk and debrief pilots who had indeed flown in combat missions; Lyndon Johnson himself, who constantly wore his Silver Star pin in his lapel, was given to regaling Washington dinner parties with stories of his encounters with Japanese Zeroes, although his only brush with combat had been to fly as an observer on a single mission, during which he was in action for a total of thirteen minutes, after which he left the combat zone on the next plane home. Exaggeration was a staple of the politician’s stock-in-trade; understanding that, congressmen discounted stories about wartime heroism. And stories about a war faded before Jack Kennedy’s conduct in Washington, for sometimes he seemed to be doing his best to reinforce the stereotype. Everyone on Capitol Hill seemed to know that he lived in a Georgetown house that was so filled with his friends, and with movie industry friends of his father’s, dropping in from out of town, that it seemed like a fraternity house, or, as one friend said, “a Hollywood hotel”; that he had his own cook and a black valet, who delivered his meals to the House Office Building every day. And everyone seemed to know about the glamorous women he dated—one, whom he dated until he told her he couldn’t marry her, was the movie star Gene Tierney; sometimes his charming, apparently carefree smile would be in magazines after he was photographed with these women in New York nightspots, and he would drive them around Washington in a long convertible with the top down: the very picture of a dashing young millionaire bachelor playboy. Watching Jack stroll onto the House floor one day with his hands in his pockets, a colleague said his attitude suggested: “Well, I guess if you don’t want to work for a living, this is as good a job as any.”

And he was on Capitol Hill much less than he was supposed to be. During his first year in Congress, he took an active role on the Housing Committee, giving a series of speeches on the postwar housing crisis, and when the Taft-Hartley Act was introduced, he opposed it on the House floor. But that fall, while he was vacationing in England after Congress had adjourned, he fell ill, and although when Congress convened in 1948, he was back on Capitol Hill, announcing that his attack of “malaria” was over, he was no longer active at all, and thereafter his rate of absenteeism was one of the highest in the House. “He had few close political friends,” one of his biographers puts it, and even those few could not pretend he was an effective congressman. His closest friend—“about his only real friend on Capitol Hill”—Florida congressman (later a senator) George Smathers, recalls that “he told me he didn’t like being a politician. He wanted to be a writer.… Politics wasn’t his bag at all.” And, Smathers recalls, “He was so shy … one of the shyest fellows I’d ever seen. If you had to pick a member of that [1947] freshman class who would probably wind up as President, Kennedy was probably the least likely.” The House bored him, said his father’s friend Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas. “He never seemed to get into … political action, or any idea of promoting this or reforming that—nothing. He was sort of drifting.… He became more of a playboy.” The men who ran the House agreed. Sam Rayburn called him “a good boy” but “one of the laziest men I ever talked to.”

In 1952, he ran for the Senate, against the widely respected incumbent from Massachusetts, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr.

Favored when the campaign began, Lodge was overwhelmed by the Kennedy organization, directed for the first time by the candidate’s younger brother Robert, and by Kennedy innovation. Tens of thousands of women voters were invited—by hand-addressed, handsomely engraved invitations—to meet the candidate and what one writer called “his large and fabulous family,” including “his comely mother and three attractive, long-legged sisters.” He was overwhelmed as well by Joe’s money—some people “could live the rest of [their] lives on [the campaign’s] billboard budget alone,” one observer remarked; among the ambassador’s outlays was a $500,000 loan that rescued from bankruptcy the publisher of the Boston Post, which shortly thereafter endorsed his son—and by Jack’s charm: the attraction of his “boyish, well-bred emaciation” for women of all ages (“every woman who met Kennedy wanted either to mother him or marry him,” the Saturday Evening Post reported) was so intense it might have been humorous were it not later to become a central fact of American political life, and indeed to play a role in altering America’s political landscape. During the campaign Jack Kennedy showed a new side of himself: from Monday to Thursday, he still seemed, in Washington, merely the Georgetown playboy; from Thursday night through Sunday, he raced over Massachusetts from one end to the other; “no town was too small or too Republican for him,” an aide was to recall. By the end of the campaign, the Saturday Evening Post reported, “Jack was being spoken of as the hardest campaigner Massachusetts has ever produced.” But once he was in the Senate the House pattern was repeated (even down to elevator operators misled by his boyish looks; one of the Senate operators told him to “stand back and let the senators go first”).

During his first year in the Senate, 1953, he not only made major social news, with his spectacular marriage to Jacqueline Bouvier, but also, during the 1953 and 1954 sessions, developed proposals for New England economic expansion and took at least one stand that lifted him above the role of a senator from just a single state or region, supporting the St. Lawrence Seaway, a project long opposed by Massachusetts and New England due to apprehension over its impact on Boston’s seaport. But even during this period, he seemed to be sick quite a bit, first with one illness, then with another, although he always made light of his ailments; in July, he was hospitalized with another attack of “malaria.” And his bad back was getting worse; the marble floors of the Senate Office Building and the Capitol were hard on him; by the spring of 1954, he was on crutches; he tried to hide them before visitors entered his office, but sometimes when he went to committee meetings, there was no place to put them, and he would have to lean them against the wall behind him, in full view. He tried to play down the seriousness of his back condition, and it didn’t seem all that serious, because he was so insouciant about it. Trying to spare himself the walk through the long corridors, he requested a suite nearer the Senate floor, but he didn’t want to draw attention to the situation by emphasizing it too strongly to his party’s Senate Leader, Lyndon Johnson, and his low seniority meant that he kept the office he had. He finally stopped going back to his office between quorum calls, staying in the cloakroom or in his seat on the floor instead. Senate rules require a senator to be standing when he addresses the Chamber; his Massachusetts colleague, Leverett Saltonstall, obtained permission from the presiding officer for him to speak while sitting on the arm of his chair.

And then, in October, 1954, there was an operation on his back. Like so many of his medical procedures, this was performed while Congress was in recess for the year: most senators weren’t around, and the press wasn’t focusing on Capitol Hill. His staff made it seem as if the operation were just a run-of-the-mill back operation. When the Senate reconvened in January, 1955, he was still in the hospital, and when it was learned that he had had a second operation, on February 15, 1955, it was obvious that there were complications. Ambassador Kennedy reportedly broke into tears in a friend’s Washington office, and said Jack was going to die. But the ambassador’s friend, the publisher William Randolph Hearst Jr., quieted the rumors by saying that he had visited the ambassador’s Palm Beach residence, where Jack was convalescing, and found him “looking tanned and fit again”; for the next few weeks there were continuing reports of his imminent return to Washington, and he gave interviews in Palm Beach, after which the reporters commented on his tan. Although, in an interview at Palm Beach on May 20 with a journalist from the Standard-Times, he did make one remark out of character—“I’ll certainly be glad to get out of my 37th year”—he quickly caught himself and assured her that everything was going well, and that his situation had never been serious. “If the Senate hadn’t kept such long hours, I could have taken it easy—perhaps I mightn’t have gone to the hospital last fall. But … there’s so much walking to do at the Capitol.” And when a few days later, he finally returned to the Senate, he did so with a quip, saying that during his time away, he had read the Congressional Record every day; “that was an inspiring experience.” Acknowledging that there had been rumors that he wouldn’t return, the New York Herald Tribune said that nonetheless, “young Jack Kennedy comes from a bold and sturdy breed, and he’s back on the job again.” His concept of the job continued to differ from that of harder-working senators, however. Although upon his return, he had been “applauded by colleagues, they nevertheless found it hard to take him seriously,” says one of his biographers. “He was still young, inexperienced, ill, and, despite his marriage, a playboy with pretensions.”

Before the 1957 session ended, Kennedy rose on the Senate floor to deliver a speech on foreign relations: on the Algerian struggle for independence, criticizing not only the French refusal to allow it, but the American government’s support of the French policy. Although the historian Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. wrote that in Europe the speech identified Kennedy “for the first time as a fresh and independent voice of American foreign policy,” and the editorial page of the New York Times applauded it, it aroused anger in the foreign policy establishment; “even Democrats drew back.” And aside from that speech, his career in the Senate continued on a course that, in Capitol Hill terms, was charted toward mediocrity. Anecdotes—possibly exaggerated but certainly striking—abounded about his absenteeism and his irresponsibility. When he was asked to chair a new Foreign Relations subcommittee on Africa, it was recounted, Kennedy replied, “Well, if I take it, will it ever have to meet?” and accepted only when he was assured it wouldn’t. (Actually, it seems to have met at least once.) The fact that, due to his father’s fame, his speeches attracted more attention than those of other senators did not lead to more respect for him among his colleagues, but to the opposite: senators liked to categorize their colleagues as either “work horses,” men who studied hearing transcripts and department reports, did the donkey work on committees behind closed doors, and really made the Senate work, and “show horses,” men in the Senate only for the publicity it could bring them. Kennedy was, in the opinion of the “Old Bulls” who ran the Senate, a prime example of the latter breed.

As for Lyndon Johnson, his opinion was that the young senator from Massachusetts was a “playboy” and basically lazy. “He’s smart enough,” he told Bobby Baker at the time, “but he doesn’t like the grunt work.”

“Kennedy was pathetic as a congressman and as a senator,” Johnson was to say. “He didn’t know how to address the Chair.” He was, he said on another occasion, “a young whippersnapper, malaria-ridden and yellow, sickly, sickly. He never said a word of importance in the Senate, and he never did a thing.” During his retirement, describing Kennedy as a senator, in phrases that he knew were being recorded for posterity, Johnson used similar adjectives—and added to them four final words that were, in the lexicon of Lyndon Johnson, the most damning words of all: as a senator, Lyndon Johnson said, Jack Kennedy was “weak and pallid—a scrawny man with a bad back, a weak and indecisive politician, a nice man, a gentle man, but not a man’s man.”

THERE WERE, HOWEVER, ASPECTS of the life of Jack Kennedy of which Lyndon Johnson was unaware—and which, had he known about them, might have led him to a more nuanced reading. He might have read him differently had he known what Kennedy had gone through to get to Capitol Hill—and why he hadn’t accomplished more once he was there.

Behind that easy, charming, carefree smile on the face of the ambassador’s second son was a life filled with pain—and with refusal to give in to that pain, or even, except on very rare occasions (and never in public), to acknowledge its existence.

Born on May 29, 1917, Jack Kennedy, even as a boy, seemed always to be falling ill—and doctors were never able to determine what was wrong with him. At the age of fourteen, already strikingly thin, he began to lose weight and said he was “pretty tired” all the time, and one day he collapsed with abdominal pain. The undiagnosed illness forced him to withdraw from boarding school. At Choate, where he enrolled the next year, he was frequently in the infirmary with severe stomach cramps, high fever and vomiting, and then, in January, 1934, when he was sixteen, he had to be rushed by ambulance to a hospital in New Haven, where he was kept for almost two months of humiliating and painful tests. “We are still puzzled as to the cause of Jack’s trouble,” the wife of headmaster George St. John wrote Jack’s mother, Rose. “I hope with all my heart that the doctors will find out … what is making the trouble.” But they didn’t. For a while, the diagnosis—an incorrect one—was leukemia; prayers were said for him in chapel; later the diagnosis was changed to hepatitis, also incorrect. In March, doctors released him without having been able to determine what he had suffered from; some of the symptoms had cleared up, but he still vomited frequently, and had periodic high fevers and severe cramping pain in his stomach, and almost constant fatigue, and no matter what he tried, he couldn’t gain weight.

In June, ill again, he was sent to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, and then to a hospital there. “The Goddamnest hole I’ve ever seen,” he wrote his friend Lem Billings. “I wish I was back at school.” The tests lasted for a month. “I now have a gut ache all the time.” “Shit!!” he wrote eight days later. “I’ve got something wrong with my intestines. In other words I shit blood.” There were constant tests. “I’ve had 18 enemas in three days!!! … Yesterday, I went through the most harassing experience of my life.… They put me in a thing like a barber’s chair. Instead of sitting in the chair I kneeled … with my head where the seat is.… The doctor first stuck his finger up my ass.… Then he withdrew his finger and then, the schmuck, stuck an iron tube 12 inches long and 1 inch in diameter up my ass.… Then they blew a lot of air in me to pump up my bowels. I was certainly feeling great.… I was a bit glad when they had their fill of that.… The reason I’m here is that they may have to cut out my stomach—the latest news.” For a while the tentative diagnosis was that he had chronic inflammation of the colon and small intestine, so severe that it could become life-threatening, but at the end of the tests, as Joseph Kennedy wrote Dr. St. John, “they were unable to find out what had caused Jack’s illness.” And because of the fears about the leukemia and hepatitis, he had to live with frequent blood counts: “7,000—Very Good,” he reported to a friend once. But when Mrs. St. John visited him in the hospital, he never stopped kidding with her—“Jack’s sense of humor hasn’t left him for a minute, even when he felt most miserable,” she wrote Rose. In the Mayo Clinic and the Rochester hospital, he charmed his nurses and doctors. And at Choate, when he wasn’t in the infirmary, he was the center of a circle of friends, some of whom, like the loyal Billings, he kept for life. “I’ve never known anyone in my life with such a wonderful humor—the ability to make one laugh and have a good time,” Billings was to recall. “Jack was always up to pranks and mischief,” says another friend. “Witty, unpredictable—you never knew what he was going to do.” And except for the occasional letter to Billings, “He wouldn’t ever talk about his sickness,” another friend says. “We used to joke about the fact that if I ever wrote a biography, I would call it ‘John F. Kennedy: A Medical History.’ [Yet] I seldom ever heard him complain.” And thin as he was, he never stopped trying to make the Choate football team.

During most of Jack’s senior year at Choate, he stayed out of hospitals; in 1935, at Princeton, however, “He was sick the entire year.… He just wasn’t well,” had to withdraw—and spent nearly two months at Peter Bent Brigham Hospital in Boston. “The most harrowing experience of all my storm-tossed career,” the eighteen-year-old youth wrote Billings. “They came in this morning with a gigantic rubber tube. Old stuff, I said, and rolled over thinking naturally that it would [be] stuffed up my arse. Instead they grabbed me and shoved it up my nose and down into my stomach. Then they poured alcohol down the tube.… They had the thing up my nose for two hours.” The blood counts were very bad. “My … count this morning was 3500,” he wrote Billings. “When I came it was 6000. At 1500 you die. They call me ‘2000 to go Kennedy.’ ” A few days later, he wrote again. “They have not found anything as yet.… Took a peak [sic] at my chart yesterday and could see that they were mentally measuring me for a coffin.” But when the next year, during what a biographer calls a “brief Indian summer of good health,” he enrolled at Harvard, he tried out for end on the freshman football team. “He was pathetic because he was so skinny. You could certainly count his ribs,” one member of the team recalls. The captain, Torbert Macdonald, who was to become another lifelong friend, counted something else, however. “As far as blocking and that sort of thing, where size mattered, he was under quite a handicap,” he was to write. But, he added, “Guts is the word. He had plenty of guts.” He made the freshman second team, until coaches found out about a party he organized at which a number of players, in his words, “got fucked,” after which he was demoted to the third team. Nonetheless, although he had barely made the team, he had made it.

LATE IN 1940, having turned his Harvard honors thesis into a best-selling book, Why England Slept, he felt a sudden pain in his lower back, as if “something had slipped,” and not long afterwards his back started to hurt him so badly that he was hospitalized; some years later, when he was operated on, the surgeons would find puzzling deterioration in his lumbar spine, with “abnormally soft” material around the spinal disks, almost as if the spine had rotted away; there would be speculation then that adrenal extracts which had been prescribed for his stomach and colon problems had caused his spine to deteriorate. He was forced to wear a canvas-covered steel brace. But when, in the summer of 1941, it became obvious that war was coming, he tried to enlist. And when, despite his attempts to conceal his condition, he was unable to pass physical examinations for either the Army or Navy, he kept trying—first spending five months trying to build up his back through calisthenics so that he could pass another examination and, then, when that didn’t work, insisting that his father arrange for a special, in effect fixed-in-advance, examination by a Navy Board of Examiners that, in October, cleared him to enlist.

His back spasms grew rapidly “more severe,” and the pain “very bad”; during training, he had to sleep on a table instead of a bed. Despite his efforts to hide his condition, he had to go to a Navy doctor, who declared him unfit for duty; he was given permission to visit the Mayo Clinic, where he was told an operation to fuse his spine was necessary. But he chose sea duty instead, and used all his father’s influence to get it—once, when his father, worried about his condition, didn’t move fast enough for him, he went to his grandfather, former Boston mayor “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald, who interceded with Massachusetts senator David Walsh, whose word as chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee was law with the Navy—and the duty Jack Kennedy chose was, of all possible assignments, one for which a man with a bad back was particularly unsuited: service on speedy patrol torpedo boats. With a back as sensitive as Kennedy’s, any jolt hurts, and on the small, thin-hulled PT boats, it sometimes seemed that every wave was a jolt; “the bucking bronchos of the sea,” a magazine writer named them after spending a day aboard—“ten hours of pounding and buffeting.… Even when they are going at half speed it is about as hard to stay upright on them as on a broncho’s back.” And at top speed, “planing over the water at forty knots and more, with bows lifted, slicing great waves from either side of their hulls, they gave their crew ‘an enormous pounding.’ ” Kennedy “was in pain, he was in a lot of pain,” a fellow trainee was to recall. “He slept on that damn plywood board all the time and I don’t remember when he wasn’t in pain.” In desperation, he went to his father, hoping that an operation could be arranged, and that he could recuperate quickly enough to go back on duty. “Jack came home,” his father wrote Jack’s older brother, Joseph P. Kennedy Jr., “and between you and me is having terrific trouble with his back.” But the lengthy recuperation period that would be required for an operation made that plan unfeasible, and Lieutenant Kennedy went back to duty, persuading Senator Walsh to arrange his immediate transfer to the South Pacific—where, on the night of August 1, 1943, the boat he was commanding, PT-109, was part of a patrol torpedo squadron sent to intercept a Japanese convoy of troop carriers, escorted by destroyers, as it came through a strait in the Solomon Islands.

The action was not successful—it was, according to one account, “the most confused and least effective action the PTs had been in”; only half the boats fired their torpedoes, and none caused any damage—but if, in a starless, “pitch dark” night with only four boats equipped with radar and all the boats enjoined to radio silence, there was confusion, there was none about what happened after a Japanese destroyer, looming suddenly out of the dark, smashed into PT-109, slicing it in half.

One half of the boat sunk immediately, the other half remained afloat. Two of the crew were dead; Kennedy and ten others were alive, he and four men on the hull, the others widely scattered, including two, Charles Harris and the boat’s thirty-seven-year-old engineer, Pat “Pappy” McMahon, who were near each other about a hundred yards away. All were wearing their kapok life jackets. Harris shouted, “Mr. Kennedy! Mr. Kennedy! McMahon is badly hurt.” Shedding his shoes, shirt and revolver, Kennedy swam to the engineer, whose hands, arms and neck were so badly burned that they were only raw flesh, and began towing him back to the half of a hull. A wind kept blowing the boat away from them. Harris, swimming beside him, said, “I can’t go any farther.”

“For a guy from Boston, you’re certainly putting up a great exhibition out here, Harris,” Jack Kennedy said. Harris stopped talking and kept swimming, and eventually the three men reached the hull. Like the others, they fell asleep on the tilted deck.

As John Hersey related in The New Yorker, after interviewing Kennedy and members of his crew some months later, there wasn’t room on the hull for all the men, and it was beginning to sink, so when daylight broke, Kennedy ordered the uninjured men into the water, and went in himself. All morning they clung to the hull, and finally Kennedy decided they would swim to a small island, one of a group of little islands about three miles away. Nine of the men made the swim hanging on to a large timber from the boat. Pappy McMahon was unable to do even that. Slicing loose one end of a long strap on McMahon’s life vest, Kennedy took the end in his teeth, and told McMahon to turn on his back. Then he towed him, swimming the breaststroke, his teeth clenched around the strap.

The swim took five hours. After he pulled McMahon up on the beach, Kennedy lay on the sand, exhausted. “He had been in the sea, except for short intervals on the hull, for fifteen and a half hours,” Hersey relates. But he lay there only for a few minutes, and then he got up, and tied his life vest back on to go back into the water. He had realized that beyond the next small island was Ferguson Passage, where PT boats sometimes patrolled. His men tried to dissuade him from going, saying he was tired, and that the currents in the passage were treacherous. Tying his shoes around his neck, he swam out into the passage, carrying a heavy lantern wrapped in a life vest to signal passing boats. It took him about an hour to swim out far enough into the passage so that he felt a boat could see him, and he stayed there, treading water, holding the heavy lantern, for hours, until, finally, he realized that no boats would be coming.

Trying to get back to the island, he was too tired to fight the current, which carried him right by it. He stopped trying to swim, and, as he later told Hersey, “seemed to stop caring.… He thought he had never known such deep trouble.… His body drifted through the wet hours, and he was very cold.” He got rid of his shoes. But the lantern was his only means of signaling, and he never let go of it. “He drifted all night” with his fist “tightly clenched on the kapok.” When the current, which had carried him during those hours in a huge circle, finally deposited him back on the second small island, he was still holding it. Crawling up on the beach, he vomited, and passed out.

The next day, he decided they would have a better chance of finding food, and of making contact with the Navy, on another of the islands. Swimming to it took three hours, the other men hanging on to the timber again, Kennedy again towing McMahon by clenching the strap in his teeth.

Hungry and thirsty, his men started to despair, but Kennedy never stopped trying to get them rescued. The cuts on his bare feet from the sharp-edged coral reefs were so festered and swollen that his feet “looked like small balloons,” but he and one of his men crossed other reefs and swam to another island, where they found a Japanese cache of food to take back to the rest. Then he found a native canoe. With the wind rising, he had to order a member of his crew to help him take the canoe with the food out into Ferguson Passage: “the other man argued against it; Kennedy insisted.” Waves five and six feet high swamped their canoe, and as the two men clung to it, the tide carried them toward the open sea while they pushed and tugged the craft to try to turn it toward the island. “They struggled that way for two hours,” Hersey wrote, “not knowing whether they would hit the small island or drift into the endless open.” Eventually the tide carried them toward the island, but first they struck a reef around it; the waves crashing on the reef tore them away from the canoe, and spun Kennedy head over heels so that “he thought he was dying” until he suddenly found himself in a quiet eddy. While he was away on one of his trips, two friendly natives came upon the crew and told them their squadron had given them up for lost. When he returned, Kennedy scratched a message to his squadron on a coconut shell for the natives to take away with them, and two days later, on the sixth day of their ordeal, his note having been delivered, they were rescued.

DURING THIS EPISODE, the pain in his back had grown worse, and so had his stomach, but he insisted he was all right. New PT boats were being fitted out with heavier guns, and he wanted command of one. “He wanted to get back at the Japanese,” his squadron commander was to recall. “He got the first gunboat,” PT-59. And the commander would recall that “I don’t think I ever saw a guy work longer, harder hours,” as it was being made ready for sea. His crew were all volunteers, five of them from PT-109—one remembered how they went down to the dock where the skinny lieutenant was fitting out the new ship. “Kennedy said, ‘What are you doing here?’ We said, ‘What kind of a guy are you? You got a boat and didn’t come get us.’ Kennedy got choked up. The nearest I ever seen him come to crying.” His new executive officer later said that “what impressed me most … was that so many of the men that had been on PT-109 had followed him to the 59. It spoke well of him as a leader.”

Kennedy had six weeks of action on PT-59, on one occasion sinking three Japanese barges. Finally, he was no longer able to walk without the aid not only of a back brace but of a cane as well, he was terribly thin, and his stomach pain had become so intense that he had to see Navy doctors, who found “a definite ulcer crater.” X-rays of his back found a chronic disk disease that had obviously been aggravated by the pounding inflicted on the boats. Shipped home, he had his back operated on in June, 1944, but the operation, for a ruptured disk, didn’t work; obviously something else was wrong: the “abnormally soft cartilage” was found; the degeneration of his lower spine was wider than had been feared—the surgeons had no real explanation; when he tried to walk again, the pain was so bad that it could be controlled only by what one of the surgeons calls “fairly large doses of narcotics.”

“PT-109” WOULD BECOME a highly publicized saga of courage and duty—members of Jack Kennedy’s crew would talk in later years of his obvious feeling of obligation to get as many of them back to safety as possible, no matter what the cost to himself. The courage required for that episode, however, had had to last for only six days. What came next in Jack Kennedy’s life—his campaign for the House of Representatives in 1946—would require courage for much longer than that, and on more levels.

His older brother, Joe Jr., had been the one who had been supposed to make that race; he was the Kennedy boy, handsome, poised, outgoing, who was destined for politics and who embraced the destiny, but Joe had been killed in the war. No one could have seemed less suited to take over his role than Jack. “Joe used to talk about being President some day, and a lot of smart people thought he would make it,” his father was to say. “He was altogether different from Jack—more dynamic, sociable and easygoing. Jack in those days … was rather shy, withdrawn and quiet.” He did not, the ambassador was to say, have “a temperament outgoing enough for politics.”

HIS FATHER’S MONEY played a huge role in the campaign, buying unprecedented amounts of radio, newspaper and billboard advertising, but his father’s money couldn’t get him onto the street corners, and into the bars—couldn’t help with his shyness.

His father’s money couldn’t help with the speeches.

At a talk he gave at a Rotary Club, not only was he so thin that, in the words of one Rotarian, “the collar of his white shirt gape[d] at the neck” and his suit “hung slackly” from his shoulders but the speech itself contained “No trace of humor.… Hardly diverging from his prepared text, he stood as if before a blackboard, addressing a classroom full of pupils.” His early speeches all seemed to be, a biographer has written, “both mediocre and humorless … read from a prepared text with all the insecurity of a novice,” in a voice “tensely high-pitched,” and with “a quality of grave seriousness that masked his discomfiture.… He seemed to be just a trifle embarrassed on stage.” Once, afraid he was going to forget his speech, his sister Eunice mouthed the words at him from the audience as he spoke.

There were, however, moments even in these early speeches when something different happened. When he stumbled over a word, “a quick, self-deprecating grin” would break over his face—and, a member of one audience remembers, it “could light up the room.” And there was, however much he stumbled over his words, “a winning sincerity” in his speeches.

And sometimes what happened during a speech was something special. At one forum in which all the candidates spoke, the master of ceremonies, no friend to Kennedy and eager to emphasize that he was a rich man’s son, made a point of introducing each of the others as “a young fellow who came up the hard way.” Then it was Kennedy’s turn. “I seem to be the only person here tonight who didn’t come up the hard way,” he said—and suddenly there was the grin, and the audience roared with laughter, and that issue was dead.

And sometimes there was something more than wit. A pol from the district’s tough Charlestown area, Dave Powers, who had turned down Kennedy’s offer of a campaign job, saying he was a friend of one of his opponents, saw it happen one night when Jack Kennedy was addressing a meeting of Gold Star Mothers, mothers who had lost a son in the war. Kennedy’s prepared speech was just something he read from a text, but at the end, as he was about to step down, Jack Kennedy paused, and said in a slow, sad voice, “I think I know how all you mothers feel because my mother is a Gold Star Mother, too.”

Suddenly women were hurrying up to the platform to crowd around Jack Kennedy and wish him luck, coming up to try to touch him. “I had been to a lot of political talks in Charlestown but I never saw a reaction like this one,” Powers was to recall. “I heard those women saying to each other, ‘Isn’t he a wonderful boy, he reminds me so much of my own John, or my own Bob.’ They all had stars in their eyes. They didn’t want him to leave. It wasn’t so much what he said but the way he reached into the emotions of everyone.”

Everyone. Not just the mothers. As Jack Kennedy was walking out of the hall, Powers told him what a “terrific” speech he had given. “Then do you think you’ll be with me?” Kennedy asked.

“I’m already with you,” Powers said.

AND HIS FATHER’S MONEY couldn’t help with the pain.

Jack was better when he rested a lot; a long, strenuous day intensified the symptoms—the nausea and the gripping stomach cramps—that the doctors couldn’t explain, and of course a long day put more strain on his back. But his days were very long. He was up early—early enough to be standing at the gates of the district’s factories so he could shake hands when the morning shift arrived at seven o’clock, and then he would go house to house through the district’s working-class neighborhoods, then ride trolley cars and subways and return to the factories at four, when the next shift arrived, then to his hotel for a long soak in a hot tub to ease the pain in his back, and then, in the evening, out to speeches at local clubs and organizations and to house parties arranged by his sisters, where, as a biographer wrote, “he was at his best, … coming in a bit timidly but with his flashing picture magazine smile, charming the mothers and titillating the daughters.”

On the last day of the campaign, there was a parade, the annual Bunker Hill Day parade, a five-mile walk on a hot June day, during which spectators kept running up to him and grabbing his hand, which of course pulled at his back. “Jack was exhausted,” recalls a supporter, a Massachusetts state senator. At the end of the parade he collapsed. Carried to the senator’s home, “he turned very yellow and blue,” the senator says. “He appeared to me as a man who probably had a heart attack.” His friends took off his clothes, “and we sponged him over.” When they got in touch with the ambassador, he said it was a malaria attack and asked if Jack had his pills with him. When he took them, he started feeling better, and the next day, he won the election.

AND SO, if after his promising first, 1947, session in the House of Representatives, his work there fell off, part of the reason could be attributed to something other than laziness.

While visiting his sister Kathleen in England after the session, he fell so ill that he was rushed to a London hospital, where there was finally a definitive diagnosis: he had Addison’s disease, an illness in which the adrenal glands fail—and that includes among its symptoms the nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite, inability to gain weight, fevers, chronic fatigue and yellow-brown coloring from which he had been suffering for years—and whose sufferers have a high mortality rate. So ill was he that the examining physician told Pamela Churchill, “That young American friend of yours, he hasn’t got a year to live.” Brought back to America in the ship’s hospital of the Queen Elizabeth, he was given last rites by a priest who came aboard in New York. He was taken on a wheeled stretcher, ghostly pale, horribly thin, so weak he couldn’t raise his head, to a chartered plane, and then by ambulance to New England Baptist Hospital, where “it was touch and go” for a while. But he recovered, with the help of new drugs that had been causing the mortality rate from Addison’s to drop dramatically. In 1949, moreover, a new drug, cortisone, would prove to be a “miracle drug” for Addison’s: thereafter, every three months 150-milligram pellets, first of cortisone and later of corticosteroid, a cortisone derivative, were implanted in his thighs, and he took 25 milligrams orally every day; his weight became normal at last, and from that time on, the abdominal symptoms didn’t bother him as much. Cortisone gave him, as a friend wrote, “a whole new lease on life.”

AS SOON AS he started to recover, there became more and more evident another aspect of the text that was Jack Kennedy, an aspect previously not as visible as the pain and the struggle against it—an aspect that Lyndon Johnson might have read with a particularly deep understanding.

Even before cortisone—in 1948 and 1949—while he was still so ill and had barely arrived in the House of Representatives, “Jack was aiming for higher office,” a friend says, and in 1950, he was spending three or four days a week traveling by car all over Massachusetts. Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. would be running for re-election to the Senate in 1952, and Kennedy was going to be running against him.

His back was getting worse, and he was frequently on crutches. There was, again, in 1952, the sheer, brutal impact of his father’s money—the gigantic outlays for billboard and other advertising, the $500,000 loan to the newspaper. But the cost to the ambassador was one he could easily pay; the cost to the son was not so easy to pay—although it was paid without a murmur.

Arriving for a speech, he would conceal his crutches in the back seat of his car, and his aides would see him gritting his teeth in pain as he climbed out and walked to the front door. “But,” as Dave Powers was to recall, “then when he came into the room where the crowd was gathered, he was erect and smiling, looking as fit and healthy as the light heavyweight champion of the world.” After the speech, and after standing in the receiving line, he would walk, still smiling, back to the car, and the smile would still be on his face, until the door was closed behind him. Sometimes, as they drove to the next stop, Powers would turn around and see the candidate leaning back against the seat, his teeth gritted again against the pain, his eyes closed. There was a big state to be covered; he didn’t talk about the pain, but about the need to make himself known in every section of it. Powers had tacked a map of Massachusetts on the wall of Jack’s Boston apartment and would stick colored pins in each town or city where Jack had spoken. Studying the map, Jack would point to some area with insufficient pins. “Dave, you’ve got to get me some dates around there,” he would say, and, Dave says, by Election Day, when Kennedy was elected to the Senate, by 70,737 votes out of a total of 2,353,231, it was “completely covered with pins.”

It seemed that his back was going to stop him. By the spring of 1954, the pain was so bad that, Billings wrote, “he could no longer disguise it from his close friends, and the toll it was taking on his mind and body was tremendous.” The crutches were often leaning against the wall behind him in committee hearings; he even had to hold himself up on them while delivering a speech in Massachusetts. Even with their help, he could hardly walk; it simply hurt too much.

Only an operation—a complicated fusing of two areas of the spine, with a metal plate inserted to stabilize it—could enable him to walk, doctors agreed, but an operation would be extremely dangerous because of the havoc that Addison’s played with the body’s ability to resist infection; “even getting a tooth extracted was serious,” said a doctor at Boston’s Lahey Clinic, and surgeons at the clinic flatly refused to operate; that same year, as Doris Goodwin reports, “a 47-year-old man with Addison’s underwent an appendectomy and died three weeks later from a massive infection that antibiotics were unable to treat.”

His father tried to dissuade him from having the operation by telling him that he could live a full life even if he was confined to a wheelchair; look at Roosevelt, he said. Nonetheless Kennedy told his father he had decided to have it; his mother was to write that “He told his father that … he would rather be dead than spend the rest of his life hobbling on crutches and paralyzed by pain.” The operation took place at a New York City hospital on October 21, 1954. “Thirty-seven years old, a United States senator with a limitless future before him, he succumbed to the anesthesia knowing he had only a 50-50 chance of ever waking up again,” Goodwin wrote.

Three days after the operation, the infection materialized; his longtime secretary, Evelyn Lincoln, was told that doctors did not expect him to live through the night; his family gathered at his bedside while a priest administered last rites; his father, coming from the hospital and needing someone to talk to, wandered, almost in a daze, into the office of his friend the columnist Arthur Krock; “he told me he thought Jack was dying and he wept sitting opposite me.” Recalls Rose: “It seemed inconceivable that he could once again be losing his eldest son.” Gradually recovering from the infection, Jack remained in the hospital for eight weeks, but his back wouldn’t heal—the huge incision, more than eight inches long, around the plate refused to close. In Palm Beach, where he was taken to recuperate, the scar still refused to heal, and he couldn’t walk; he could only lie on his back, in pain, “and the doctors,” as Goodwin writes, “would not say whether he would ever walk again, let alone walk without crutches.”

On February 15, 1955, a second operation was performed, and the metal plate was removed, and he began to heal—somewhat. Three months later, on May 23, he returned to the Senate, coming down the steps from his plane, and, on Capitol Hill, walking to his office, without crutches, a smile on his face. He was “tanned and fit,” the Herald Tribune said. “Aside from experiencing some difficulty in walking, the Senator looked to be in excellent shape,” the Boston Post said. But the reality was very different—as a new physician, Dr. Janet Travell, saw three days later when, in desperation, he came to consult her for the first time in her office on the ground floor of a New York brownstone.

She had read the news stories about his return to Washington, Dr. Travell was to recall. “It must have taken tremendous grit for him to create that effect.” The young senator could barely get down the few steps to her office; the taxi driver had to help him. As he sat in her office, she saw that he was too thin, and that under his tan he looked pale and anemic; “he moved guardedly” and “couldn’t turn to face her … without turning his entire body.” He answered all her questions, but did so reluctantly, “as if he were retelling a boring story.… He seemed tired and discouraged.… When I examined him, the reality of his ordeal was brought home to me by the callus under each armpit … where the skin had borne his weight on crutches for so long.”

Dr. Travell’s treatment—injection of the muscles in spasm in Kennedy’s back and legs with a solution of procaine and Novocain—worked to a considerable extent, and in remarkably short order. The pain was still there, although far less than before, and so was the brace; but the hated crutches were gone. After he began using a rocking chair she prescribed, sitting became much easier. And the cortisone kept the Addison’s, except for isolated incidents, under control: his face was no longer gaunt; he was no longer tired so often; he was, in fact, filled with energy. And after so many years of thinking he would die young, he had a different view. “Jack had grown up thinking he was doomed,” Lem Billings was to say. “Now … instead of thinking he was doomed, he thought he was lucky.” And by the 1956 convention, when he grabbed at the vice presidency, it was apparent that that was not the “higher office” he had in mind. “I’m against vice in all forms,” he joked not long thereafter, and by 1957, a large map of the United States was always spread out on a table in Palm Beach. Jack Kennedy, and his father, and visiting politicians—and they were visiting from all over the United States—would pore over it, noting “potentially valuable contacts.”

And Jack Kennedy made the contacts—and turned contacts into allies—in person, crisscrossing the country again and again. In September, an infection around the spinal fusion required hospitalization and a “wide incision,” and thereafter, as he recuperated in Hyannis Port, was so painful that his father made what must have been a difficult telephone call for him. “Maybe Jack should stop torturing himself and he should call the whole thing off,” Joseph Kennedy said to Dr. Travell. “Do you think he can make it? There are plenty of other things for him to do.” Calling it off, however, was not something Jack Kennedy was considering. Visiting Hyannis Port, Dr. Travell sat with the senator studying his schedule for the next five weeks, and trying to find time in it for rest periods. “There was,” she wrote, “scarcely a free hour.” The senator told her the schedule couldn’t be changed.

Lyndon Johnson might well have read John F. Kennedy differently than he did—more accurately. He was, in fact, particularly well qualified—almost uniquely well qualified—to do so. For all the differences between the two men, there was at least one notable similarity, and it had to do with their campaigns for office, starting with each man’s first campaign. Jack Kennedy was not the only one of the two men, after all, who had, during his first campaign for Congress, driven himself to the limit of his physical endurance, and then beyond, until at the end of the campaign—but not until the end—he had collapsed in public. Kennedy’s collapse had been in that Bunker Hill Day parade on the last day before the election; Johnson’s, during his first campaign for Congress, in 1937, was two days before the election, in the Travis County Courthouse. All during that campaign—a campaign it seemed all but impossible for him to win—he had been losing weight; during it he lost about forty pounds from an already thin frame, until his cheeks were so hollow and his eyes sunk so deep in their sockets that, as I have written, “he might have been a candidate by El Greco.” Then he began vomiting frequently, constantly complaining of stomach cramps, sometimes doubling over during a speech. The complaints were not taken seriously because he never slackened the pace that led to Ed Clark’s comment that “I never thought it was possible for anyone to work that hard,” but on a Thursday night in the courthouse—the election was on Saturday—he was delivering a speech, holding on to the railing in front of him for support, when, doubling over, white-faced, he sat down on the floor. He got up, finished the speech and then was rushed to an Austin hospital, where doctors, finding his appendix was about to rupture, operated almost immediately. Jack Kennedy was, moreover, not the only one of the two men who had fought through pain—great pain—in a later campaign. During his 1948 race for the Senate, Johnson was suffering from a kidney stone and kidney colic, an illness whose “agonizing” pain medical textbooks describe as “unbearable.” His doctor said he didn’t know “how in the world a man could keep functioning in the pain that he was in.” But he kept functioning, smiling through speeches and receiving lines even though, in the car being driven to them, his driver, looking in the rearview mirror, often saw him doubled over in pain, clutching his groin, shivering and gasping for breath. A temperature of over 104 degrees left him racked alternately by fever and violent chills. Refusing for long days to be hospitalized despite warnings that he was risking irreparable loss of kidney function, he suspended his campaign only (and even then against his will) when he could no longer control his shivering, and could barely sit upright. When, in the hospital, doctors told him that an operation to remove the stone was imperative—that with his fever, caused by infection, not abating, and the possibility of abscess and gangrene in the prognosis, his situation was becoming life-threatening—Johnson nevertheless refused to agree to one because the lengthy recovery time would end his hopes of winning the campaign, finally persuading surgeons to try to remove the stone by an alternative procedure that they were doubtful would work, but which in fact succeeded. Throughout his life, Lyndon Johnson had aimed at only one goal, and in his efforts to advance along the path to that goal had displayed a determination—a desperation, really—that raised the question of what limits he would drive himself to in that quest, and indeed whether there were any limits. Had Johnson read Jack Kennedy more accurately, he might have seen that the same question might have been asked about him. The man Lyndon Johnson was running against—this man he didn’t take seriously—not only wanted the same thing he did, but was a man just as determined to get it as he was.

Please comment below.

It was a joy to read this. I had no idea that JFK had this toughness. Remarkable

Read this whole thing. Super interesting