Nietzsche and the Zionists

Notes on the Zionist fathers and their Will to Power

The Gaza Strip was an embarrassing subject; under Egyptian rule, it was dangerously close to Israeli centers, but ruling hundreds of thousands of refugees was also a bad option. “If I believed in miracles I would want it to be swallowed up by the sea”

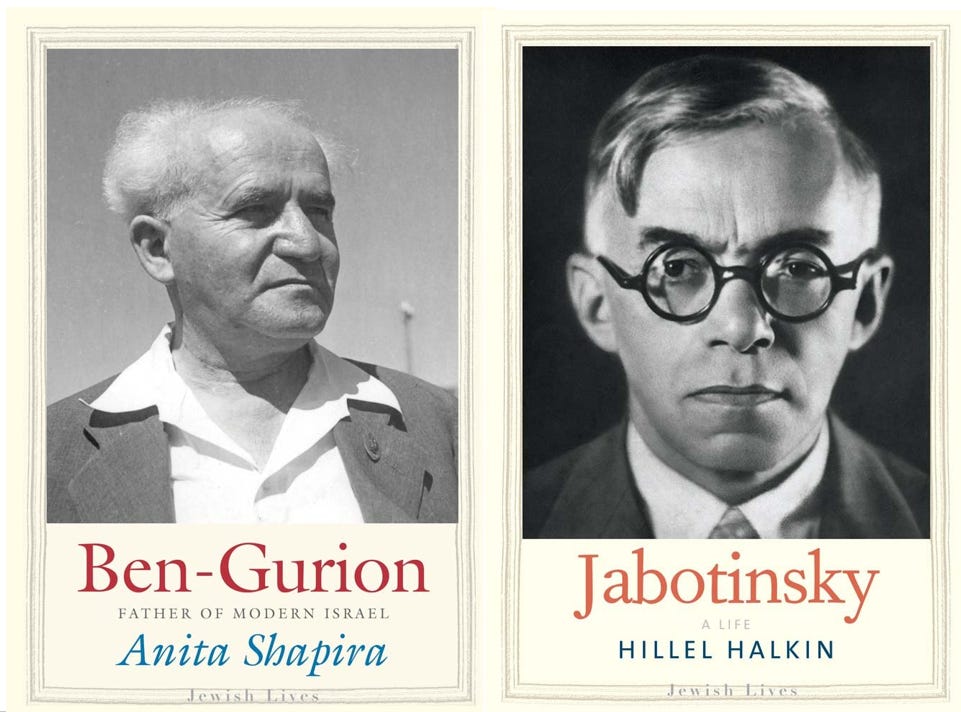

— Ben-Gurion, 1956, in ‘Ben-Gurion, Father of Modern Israel’ by Anita Shapira

Related: Herzl’s Dream, The Hundred Years' War on Palestine, On Gaza

There’s a lot that’s surprising about the lives of the early Zionist fathers. Ben-Gurion, a Plonsk shtetl Jew who in his early-teens first adopted spoken Hebrew with his Zionist compadres, singularly propelled spoken Hebrew (a rarity) to a hallmark of Plonsk’s Zionist youth. He later learned Turkish in three weeks.1 Jabotinsky was an Odessan cosmopolitan,2 an author and playwright, a cad who could flirt seamlessly in Italian and almost a dozen other languages.3 At one point he proposed to Latinize Hebrew script, following Ataturk’s example in Turkey. For pioneers of a nascent nation to be forged in war, they were surprisingly intellectual. Ben-Gurion was book obsessed, building a huge library into his first home, and startling Isaiah Berlin with his inner life.4 Jabotinsky translated Dante, Poe, and Byron into Hebrew. He wrote five novels, one of which (Samson the Nazirite) was made into a Paramount picture where he was credited (!). For an agrarian socialist, Ben-Gurion hated the farming life. For his reputation as a nationalist firebrand, Jabotinsky was not much of a warrior. His only (probable) kill was shooting a wounded Turkish prisoner his troops were unable to take with them, which haunted him for life.

Ben-Gurion’s agrarian socialism seems arcane and bizarre today, and it’s easy to forget how dominant and very literal it was in early Israel. Ponder this paragraph, for example:

Neither the Weizmann-dominated Executive nor the Labor Zionist–controlled Council wished to see a large influx of European Jews who were not interested in agricultural pioneering. Their first priority was not maximally increasing the Jewish population of Palestine... Rather, as Weizmann stated, it was ‘converting into peasant farmers an urbanized people’ as part of the transformation of values in Jewish life that Zionism stood for. (Hillel Halkin, Jabotinsky)

Jabotinsky’s nationalism and emphasis on a Jewish majority seem clearly correct. And when you look upon Israel today, it’s proven prescient. Labor is no more. Agrarian socialism is no more. Jabotinsky’s heirs in Bibi and Likud have become totally dominant. And yet, Ben-Gurion and his Labor Zionists were essential to the creation of Israel and to forging the modern Israeli. It is Ben-Gurion who towers over the history of modern Israel, not Jabotinsky. (No doubt this is at least partly because Jabotinsky died suddenly in 1940.) It took their collective wills and difficult decisions and risks to navigate the time between Herzl’s death in 1904 through WWI, WWII and the Holocaust, and the great power politics and violent pangs from which the State of Israel was born. It’s impossible to isolate a single cause — a man or thread of events — in this maelstrom. Even with the benefit of hindsight none of it seems inevitable.

We glimpse into early decisions that, each small enough at the time, have since ballooned out of all proportion. Ben-Gurion’s small decision to exclude about 400 full‑time yeshiva students from army service (assuming they’d disappear instead of metastasizing into the mass of Haredim today); fostering mass Mizrahi migration, heralding a demographic shift that now threatens to permanently cast out the Ashkenazi ruling class of the founding fathers; mimicking Britain’s lack of constitution, probably to concentrate power in Ben-Gurion’s ruling executive, leading to decades of Supreme Court power accumulation culminating in the current judicial reform crisis. And then there are the Arabs…5

One thing clearly binds the arch-rivals: an explicit belief in their own indomitable wills. Incredibly, it appears that in the incredible milieu of ideas that percolated in the early 20th century, they both picked up direct Nietzschean influences via writer and thinker Micha Yosef Berdyczewski.

Here are two paragraphs from Shapira’s Ben-Gurion biography, the latter quoting from a letter by Ben-Gurion:

Among the Zionist thinkers [Ben-Gurion] respected Ahad Ha’am as a pure-minded writer and an important critic, but his heart lay with Micha Yosef Berdyczewski, Ahad Ha’am’s sworn adversary and the man who introduced Nietzschean ideas into the Jewish milieu. Shlomo Zemach later wrote: “We, the young people of Plonsk, would walk down Ploczk Street with the Nietzschean phrases we learned from Berdyczewski on our lips, and pondered life as death and death as life, not understanding much about it, yet taking in something of it.”

“The desire to strive for the rebirth delegated to us by the man with the will of the gods will burn within us until completion of the great task, for which the great leader sacrificed his illustrious life.” The typically Nietzschean expression he used, “the man with the will of the gods,” alludes to a leader’s most notable quality—willpower—linking it to the legacy Herzl has supposedly left young people: the task of navigating the ship of Zionism to a safe harbor.

And this on Jabotinsky by Halkin:

What Zionism had to offer them was the freedom, in a national framework of their own, to be whatever they chose to be without fearing the loss of national identity that came with assimilation. This aligned him with secular critics of Ahad Ha’am like Micha Yosef Berdichevsky and Jacob Klatzkin who denied essential qualities to Jewishness, which was simply what Jewish life made of it.

In their different ways, both men absorbed this idea, moving beyond their inherited traditions to bend history to the will of a new Jewish self. Jabotinsky and Ben-Gurion both believed in an agentic nation, a people who would make of themselves what they chose. And each lived that same forceful will in leading their respective Zionist movements against their enemies and each other. For Jabotinsky, moving away from journalism and towards something of substance was a matter of existential will:

He had begun to think of journalism as a futile profession. To Razzini he wrote that it was “ruining my nerves” and that, though it paid well and had made him “cheaply popular,” he would have to abandon it. In April 1902, shortly before his arrest, he had published a feuilleton entitled “Clowns” in which he compared himself and his fellow journalists to circus performers, using every possible trick to entertain a bored public. In another piece, called “Helplessness” and published in September of that year, he related a conversation with an eighteen year-old girl who had turned to him because she had no money for the operation needed to save her mother’s life. “I’m sorry, miss, there’s nothing I can do,” he apologized to her before telling his readers: “How gladly I would trade all the words I know and all the fire I can breathe into them for one true act! Let it be modest, let it be unnoticed—but let it be true.”

It’s striking how mortal both leaders appear, at least in the tellings of Shapira and Halkin. Both were prophetic, but deeply fallible. My favourite Ben-Gurion mistake was how he bet on the Ottoman empire in WWI:

Ben-Gurion and Ben-Zvi disembarked in Jaffa sporting thick mustaches, red fezzes, and Turkish-style suits. This Ottoman look reflected their belief that the future of Jewish Palestine depended on the attitude of Turkey, so the correct policy was to gain Turkey’s trust in its Jewish subjects.

Ben-Gurion is at his most mortal as he approaches death. Sidelined during the 1967 war, he lives out his final days in his kibbutz home, alone and not altogether there. A towering figure in Israel at his zenith, he ends life shrunken and, like all men, returns to nothing.

What would they have been today? What hinge of history would they have pressed on? How would they have forced the world to their wills? Probably they would have just been fine middle class professionals — lawyers or academics or writers — complaining about house prices. It was both their curse to live through the greatest horror to befall their people, and their greatest blessing to answer the call of destiny to lead them out of bondage to the promised land.

PS. Isn’t Ze’ev (or Zev) just a fantastic boy’s name? God willing…

He studied Turkish intensively and discovered a previously unknown talent, astounding his teacher by how rapidly he grasped the language. After only three months he could read a Turkish newspaper, and a month later he swapped roles with his teacher; instead of the teacher teaching him Turkish, Ben-Gurion taught him Hebrew and turned him into a Zionist.

Jabotinsky’s cosmopolitanism is one of his most underrated and most modern characteristics, and this difference with the other Zionists is both deep and astutely made out by Shapira:

All this does not add up to an “assimilated” Jewish background. Why, then, did the myth of one develop? In part because, to other Eastern European Zionist leaders of his generation like Chaim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, Jabotinsky really did seem a kind of half-breed. The Weizmanns and Ben-Gurions were products of the shtetl. They were raised in Yiddish; were given their first education in the heder, the religiously Orthodox Jewish schoolhouse in which secular subjects were rarely taught; socialized as boys exclusively with other Jewish youngsters; and learned the languages of the generally anti-Semitic Poles, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and Belarussians among whom they lived only later. Their world was divided into Jews and non-Jews, the latter viewed as alien and hostile. Ben-Gurion, who in the 1930s headed the more diplomatically and territorially compromising Zionist Left against the more militant Right led by Jabotinsky, once remarked that the latter was the only Zionist politician he knew who had not the slightest instinctive fear of Gentiles and could never be intimidated by them. Although this was meant as a compliment, the inference was, as Weizmann was to put it more baldly in his autobiography Trial and Error, that Jabotinsky had something “not at all Jewish” about him.

He could have been anything, he could have been anyone. He gave up a thriving literary and journalistic career for a cause he believed in.

Despite a generally seriousness and lack of personal charm, Ben-Gurion also had a softer side, forming a lifelong unconsummated (?) romance with a younger former secretary, Miriam Taub (nee Cohen). Their love letters became more prosaic over time, wilting into this beautiful formulation:

Their correspondence over the years included ritual statements whereby her husband sent his regards to Ben-Gurion, and Miriam sent her greetings to Paula. But in one letter she explained that “letters leave so much more unsaid than said, that sometimes I think one should write them only when very young—before one has learned all the things not to say.”

He preferred to talk with the philosopher Isaiah Berlin rather than meet with London dignitaries. “He is the only statesman I have ever met in my life who possesses a rich inner life, distinct from public achievements however heroic: and . . . this is something so rare, valuable and marvelous that I should like to express here, sincere and profound homage to it,” Berlin wrote admiringly after their meeting, in which the talk centered on Indian mysticism, the role of elephants in Indian folklore, and Plato.

Benny Morris, Israel’s most (?) famous living historian once had some sharp words for Ben-Gurion — blaming him for hesitating and not going far enough with Arab expulsions:

But I do not identify with Ben-Gurion. I think he made a serious historical mistake in 1948. Even though he understood the demographic issue and the need to establish a Jewish state without a large Arab minority, he got cold feet during the war. In the end, he faltered.

…

If he was already engaged in expulsion, maybe he should have done a complete job. I know that this stuns the Arabs and the liberals and the politically correct types. But my feeling is that this place would be quieter and know less suffering if the matter had been resolved once and for all. If Ben-Gurion had carried out a large expulsion and cleansed the whole country – the whole Land of Israel, as far as the Jordan River. It may yet turn out that this was his fatal mistake. If he had carried out a full expulsion – rather than a partial one – he would have stabilized the State of Israel for generations.

So Jabotinsky is another example of “the non-Jewish Jew?”