Of Kings and Immigrants

Napoleon, the Pumpkin King, the Lion King, and the only Georgian in Shreveport, Louisiana

“There was nothing exceptional in him but for the fact that he could never seem to be ordinary. He had some mark on him, like a migrant or a priest.”

— Cloudstreet, Tim Winton

I spoke with Alexander Mikaberidze, author of the excellent The Napoleonic Wars: A Global History, which I highly recommend.

You may have noticed from his surname (-idze) that Mikaberidze is Georgian. And I discovered as I spoke to him that he is very Georgian indeed and the only Georgian living in Shreveport, Louisiana. Much of the interview is really about the immigrant experience: building anew, maintaining identity, cultural continuity and trade-offs. Not only his personal experience, but the experiences of Napoleon (a Corsican French Emperor), the Mamluk Georgians, a Danish ruler of Iceland, and an Albanian founder of modern Egypt, all coursed through our conversation.

So in this Kvetch, in addition to the podcast, I also look at two films that on one reading touch on exactly these questions: The Nightmare Before Christmas and The Lion King. What do their cartoon kings tell us about immigration, governance, and intra-elite competition? Spoiler: they may be the most reactionary films ever: anti-immigration, pro-Monarchy, anti-fascist, anti-democracy.

I am indebted to an excellent Kvetch reader who wishes to remain anonymous - I borrow heavily from him for The Nightmare Before Christmas observations below.

In this Kvetch:

Napoleon and the only Georgian in Shreveport, Louisiana

The Nightmare Before Christmas

The Lion King

1. Napoleon and the only Georgian in Shreveport, Louisiana

You may also like my interview (full transcript available) with Thomas Wier and Dr Timothy Blauvelt on Georgian history and language.

How did Georgia, with its unique language, survive sandwiched among empires?

Georgian histography and the origins of the Georgian language

How has the perception of Napoleon change over time

Is history fake?

Did Napoleon only eat one meal at the academy so that he could afford to buy himself books?

Napoleon, Jørgen Jørgensen, Mehmet Ali (Albanian founder of modern Egypt): the charisma and power of the outsider

Mamluks and the prominent roles of Georgians, their continued involvement with Georgia and how their nepotistic preference for Georgian slaves generated demand for Georgian captives

Georgian cuisine

What is most striking thing about living in Louisiana?

The role of Great Men in history

2. The Nightmare Before Christmas

I’ve written before about how Nightmare may give us our greatest on-screen hero - a great King, beloved by his people, master of his craft, compelled by a yearning to do something Great: the Master of Fright, Jack the Pumpkin King.

But the story can be read another way: Nightmare is about how open immigration between different cultures inevitably leads to conflict, and all sides suffer—"multiculturalism" is actually a sick parody of what it's trying to embrace (exemplified by the song "Making Christmas").

This dinner scene from Annie Hall comes to mind as an example of the line that (in this scene literally) splits immigrants from their host cultures. I will let you decide whether it’s the rough immigrant Jews or the prissy WASPs who are the residents of Halloween Town in this example.

As I noted here, the ethic of this universe is contemptuous of democracy — Halloween Town's mayor, sporting a big MAYOR badge, is merely a sycophantic event-coordinator. At Jack the Pumpkin King's absence he scurries around crying:

I'm only an elected official here, I can't make decisions by myself!

But whilst the story is pro-monarchy, it's also anti-fascist. Oogie Boogie is powerful, but ugly — he's a big sloppy sack, while Jack wears a perfectly-tailored suit. And Oogie Boogie is powerful, but only because he's made up of the collective efforts of lots of disgusting bugs. He also has a band of thugs who inflict random violence on his behalf. He's a metaphor for far-right populism.

In the end, Jack returns to his homeland, and has a family. He still visits with Santa: cultural exchange can be valuable, but only if it's restricted to elites, all of whom happen to be absolute monarchs.

3. The Lion King

The Lion King is similarly pro-monarchy and anti-fascist. Mufasa and his son are the true rulers of Pride Rock, as befitting a hereditary monarchy. The villain is the usurping Scar, emasculated in his weaker stature,1 siccing his goose-stepping hyena army on the nobility of the land.

Rule is a question of intra-elite competition: there is not even the question of a zebra or a mongoose ruling the joint, only which lion. Virtue is supreme: you want a virtuous king and aristocracy over thuggish brutes. There are also no qualms about elites (again, literally) feeding off their subjects. It is only a question of how much. Elites even have a theory to justify the subjugation and periodic slaughter of their subjects: the circle of life. Yet there is a balance: excess feast begets famine. Scar and his stormtrooper hyenas ravage the lands to destitution. No, The Lion King says, a Good Monarch will keep a House that will feed moderately off its subjects.

And like Nightmare, The Lion King also has stern words for would-be immigrationists: you are tied to your land. The shadow land is physical — it belongs there as you belong here. Migrating may be for antelope but not for lions. When Simba goes to the rainforests of Timon and Pumbaa he tries to assimilate and live by the ways of a new culture. It’s even somewhat successful — a lion grows up on bugs after all. But it’s not his place. He will not eat the bugs. He must r e t v r n.

The metaphor for human biodiversity is even a little on the nose: some are made to rule, others to be ruled, others to be vicious thugs.

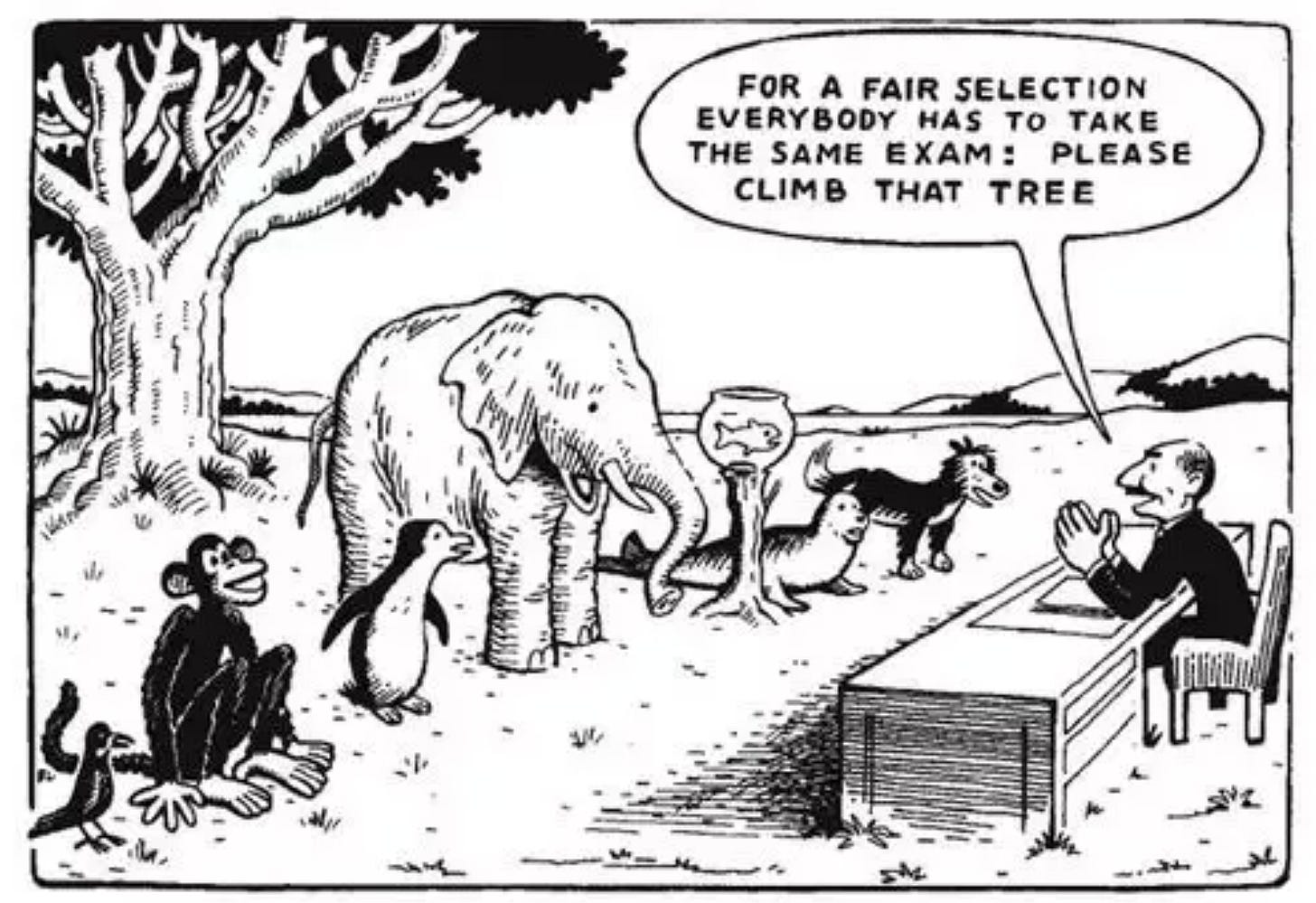

Which is not really out of sync with modern discourse. This cartoon which periodically makes the rounds makes the same point: