Warren Mundine in Black and White

A memoir of middle Australian aspiration, loss, politics and Aboriginal identity

"Change everything just a little so as to keep everything exactly the same.''

The prince in Lampedusa's The Leopard

Aboriginal women… are more than thirty times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of family violence and ten times more likely to die from a violent assault than other Australian women.

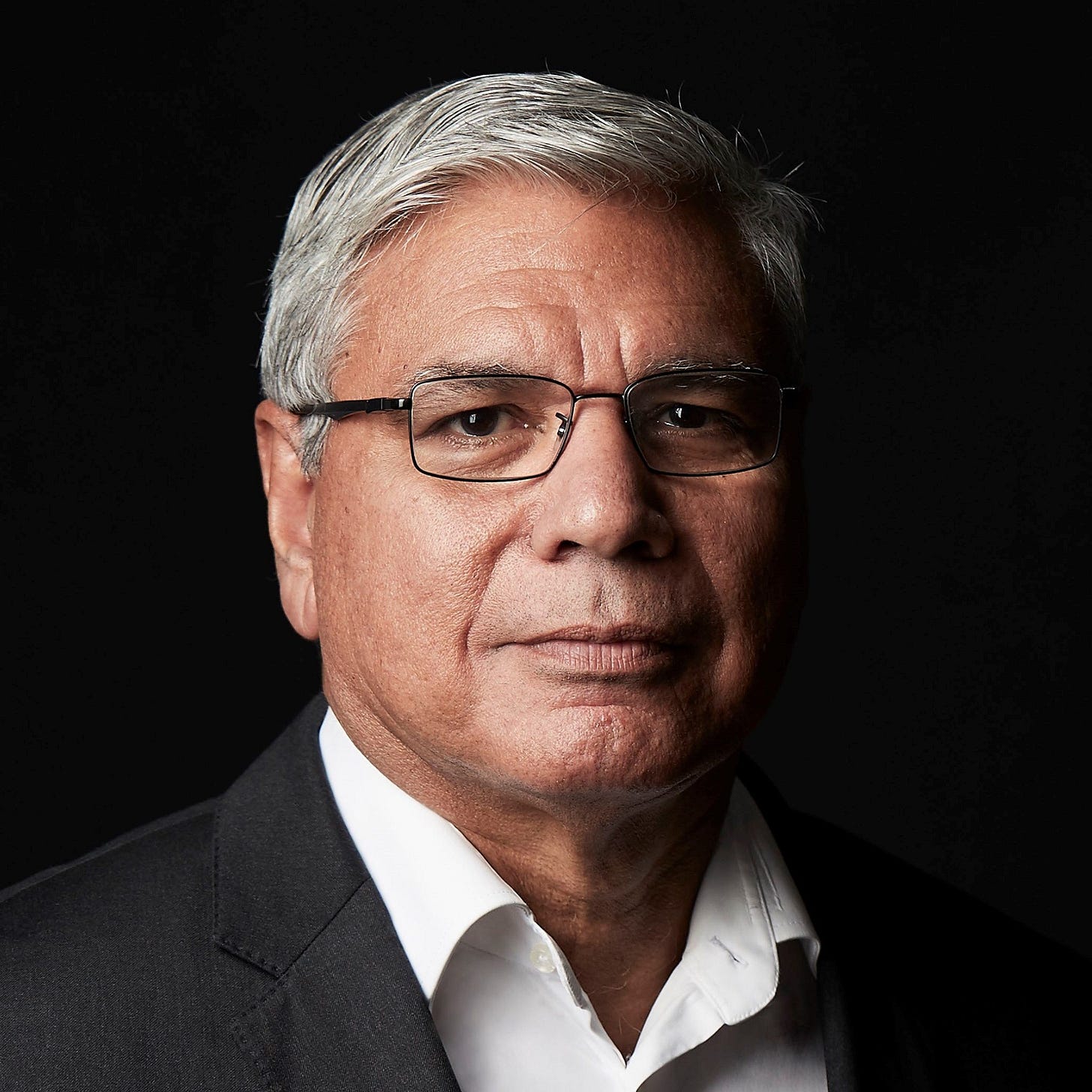

Nyunggai Warren Mundine

Nyunggai Warren Mundine’s memoir Warren Mundine in Black and White is the surprisingly frank story of an Aboriginal boy from regional New South Wales who moves to Sydney as a laborer, returns to the country to succeed in local politics, and proceeds to national relevance within the Australian Labor Party. Relevance, but ultimately political failure. After being National President of the ALP, Mundine never gets a chance to run in a federal election as the political power brokers run rings around him. After he published this memoir, he was given a chance: by the Liberal Party. He ran in 2019 and lost.

Born in 1956, his life follows the arc of Australia-Aboriginal emancipation and disappointment. Born in a time when his father wore a “dog tag” under a “protection regime” for Aboriginal Australians, he recalls Aboriginal supplication to and fear of whites. He lived through the 1967 referendum that gave Aborigines the vote, through generations of governments and their indigenous policies, countless advisory panels and funding models, all the way up to the 2008 apology, and even the the Voice (currently before the Australian people via constitutional referendum, but having germinated in 2014). And he has strong views on the subject. The ALP “runs rings” around the Liberal Party when it comes to symbolism. He’s despaired over the horrowshow of Aboriginal township violence and abuse. He’s watched cattle stations handed over to indigenous groups fail. He alludes to the endemic mismanagement that pervades indigenous groups — the incompetence and decades of litigation that soak up wealth as factions prosecute internecine feuds. This was how I came across Mundine in the first place and felt compelled to read his story: here was a politically engaged Aboriginal man on Twitter who was not towing the establishment line and who was making an awful lot of sense.

But even more than a story of aboriginality in this nation, and more than a story of political ascendency, Mundine’s story is a poignant portrait of the tragedies and travails that afflict regional and working class Australian men. Mundine grew up in a world of tin sheds and asbestos tailings dumped by mining companies and stuffed by aunts into sewn sheets to make eiderdowns. Kids played barefoot in the white dust that led to many of Mundine’s family dying prematurely from dust diseases. His brother lost a leg serving in Vietnam. Mundine was nineteen when he knocked up his seventeen year old girlfriend and made an honest woman of her — they catered their wedding with KFC — until that failed. She turned out to then make even more questionable life choices, partnering with a bloke who’d been in prison for child sex offences (she didn’t tell Mundine that when she looked after their kids). He married anew, had multiple kids, cheated on his wife, divorced again.1 He lived some of the recurring themes of Kvetch — power as aphrodisiac, hypergamy and value in the mating market:

I was surprised to learn how leadership and influence can make a man attractive to women. Back then I was very overweight and I’d never have thought a fat, middle-aged bloke like me would be attractive to single women. But after I was elected to the Presidential Panel, I noticed women became interested in me, even women who wouldn’t have looked at me twice when I was unemployed in Dubbo.

He describes the nadir that followed — of weight loss, paralysing depression, suicide ideation — in harrowing detail. Following his third (and current) marriage, he is estranged from his daughters. These are the harsh sinews of life that bedevil so many men, and that people in the limelight tend to push into the dark. But not for the plain talking Mundine. He lays it all out in a bleak portrait of middle Australia. There is a down-to-earth manner to his style which makes it all the more terrifying. Death, divorce, estrangement, career failure: these come for Every Man.

There is more to Mundine’s story than just middle class gloom, but I want to stay there for a moment. His story is almost a middle class Australian version of the marital derangements of Fleishman Is In Trouble, or the onset of illness in Ross Douthat’s bitter portrayal of his battle with Lyme disease in The Deep Places. I’ve become obsessed with this notion of a mass, hidden suffering in middle life. The reckoning of the realities of middle life as they impinge on the aspirations of youth. The plagues of illness, divorce, death, ennui, financial stress descending upon earlier hope and dreams. Little about earlier life prepares you for this.

I’ve kvetched on Yoram Hazony’s conception of marriage and parenting in The Virtue of Nationalism before:

the difficulties involved in raising a child already bear little resemblance to anything the young lovers may have thought they were consenting to at the time. And the project of raising children only continues to throw up ever new surprises over the decades, including hardship and pain that were scarcely imagined when they first entered into it.

I read Ross Douthatthe same way. Rather than Hazony’s hardships of marriage or Fleishman’s derangements of divorce, Douthat drinks from the cup of chronic illness:

But there was also a feeling of betrayal, because so little in my education had prepared me for this part of life—the part that was just endurance, just suffering, with all the normal compensations of embodiment withdrawn, a heavy ashfall blanketing the experience of food and drink and natural beauty. And precious little in the world where I still spent much of my increasingly strange life, the conjoined world of journalism and social media, seemed to offer any acknowledgment that life was actually like this for lots of people—meaning not just for the extraordinarily unlucky, the snakebit and lightning-struck, but all the people whose online and social selves were just performances, masks over some secret pain.

But to reduce Mundine’s story to hardship would be misleading. His story is also far from typical. From his family’s generation of eleven siblings, four received Australian honours (e.g. medals of the Order of Australia). Nor is his temperament bleak. His outlook is fundamentally optimistic. He’s raised seven children, including a foster daughter. And whilst his political and economic views tend to be a middle of the road Australiana liberalism, they can also be remarkably clear-sighted and shockingly piercing.

Mundine’s first trip overseas was when he was nearly fifty and you can feel the fresh optimism ringing through the page. He’s inspired by South Korea2, a pre-industrial nation that transformed into an advanced economy within a generation or two, while maintaining its own distinct culture.3 Jews are another group he’s “drawn inspiration from”, with their history of suffering and their transformation of Israel (where he’s visited) from a poor nation with few natural resources beset on all sides by enemies to one that is thriving and modern. Why can’t his people dream and build in kind, he wonders. Why not indeed.

He yearns to inject vitalism into indigenous aspirations:

The greatest threat to indigenous cultures is to be treated like museum pieces. Colonised peoples, too, can modernise and adapt. Our cultures, too, can embrace the best of both worlds.

In response to business leaders complaining about no jobs in the regional indigenous town of Aurukun, he notes:

Sydney was once a remote community with no jobs. Did the First Fleet turn up in Sydney Harbour and say, ‘Oh. There are no jobs. Let’s go home’? Maybe I wish they had but they didn’t. They built a thriving community and nation”

That’s a profound optimism and vision that’s rare and refreshing in Australian leaders. (I was equally surprised — and pleased — to learn that former PM Julia Gillard had asked former Treasurer Secretary Ken Henry what it would take to turn Darwin into Singapore).

Mundine is pro-nuclear, pro-energy and pro-economic empowerment. Did you know indigenous men and women cannot own property on Native Title land? Over 50% of the Australian landmass is Aboriginal under Native Title (Google it!) and indigenous Australians cannot own private property on it. With everything we know about wealth creation — urbanisation, coastal access (read: ports), property rights and free-markets, — you could not devise a system that was more destined to poverty and abuse: arid, regional communities with no private property rights. The Australian government spends $30 billion p.a on indigenous people, and doesn’t make a dent in their immiseration and we wonder why: we have ensconced them in their own ethno-communist dystopia.

The Australian government spends $30 billion p.a on indigenous people, and doesn’t make a dent in their immiseration and we wonder why: we have ensconced them in their own ethno-communist dystopia.

He is angry at and mocks the inner-city progressives who prevent indigenous groups from monetising even a tiny portion of their inheritance. He describes Woodside’s James Price Point project on the Kimberley coast. It would have delivered $1.5bn in benefits over thirty years to the Goolarabooloo Jabirr Jabirr people, in addition to the jobs and flow-on local economic effect. Navigating the compliance regime cost $1bn, 25% of the overall construction cost. Activists opposed the project on the grounds it would be destructive to the local environment. It was pulled. You can almost feel Mundine spittle with indignation:

The Kimberley is over 423,000 square kilometres. That’s about twice the size of Victoria and three times the size of England. The land area for the gas hub project was 25 square kilometres and the marine zone 10 square kilometres.

This is just one example of the environmental scleroticism that impedes economic progress in indigenous communities. Mundine portrays opposition to the Queensland Adani mine in a similar light — the investor was Indian, the traditional owners of the land were indigenous Australians, and the opposition were white environmentalists.

Mundine has lived through the metastisation of NGOs, government bureaucracies and social corporate groups serving indigenous causes and their failure to make any progress over 40 years. He’s seen them captured by their bureaucrats with endless sinecures and make-work, and the perpetuation of the issues they’re nominally meant to solve. He is cynical about politics — “if there’s no photo, it didn’t happen” — and I can’t help but think of Albo with his painted face.

His skepticism of Forever Bureaucrats, the sickly sweet cynicism of the ALP’s Forever Symbolism, and the harsh realities of Forever Failure when it comes to indigenous outcomes unquestionably comes from a deep and unabiding love for and belief in his people. He is sidelined from one committee after revealing fake housing construction reports in regional towns. On climate change he prizes Australia’s great fortune in its mineral endowment, and sees their benefits as real and Australia’s contribution to mitigating climate change as fanciful:

Australia’s efforts won’t make one bit of difference to the global climate.

Mundine represents a common-sense middle Australian conservatism: family, economic prudence, skepticism of forever bureaucrats. He’s a big Facebook user (the posher former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull prefers WhatsApp). He is shocked and bemused at being instructed at a UN function to avoid family language — no “family”, “husband and wife” or “mother and father” language, to avoid offending the LGBTIetc community. He is skeptical of the soulless global functionary’s ability to understand and impact what really matters to his people in Aboriginal communities.

Mundine comes from the Bundjalung in New South Wales — a warrior people, he notes with pride.

Electricity didn’t come to Baryulgil until the 1980s. The families used candles or kerosene lamps. They didn’t have running water either and they would walk to the river to wash and to collect water and bring it back in buckets. On wash days, the women and children would sit by the creek and wash all day. Then when the men came back from work, they’d help carry all the clothes back.

They relied on bush medicine – knowing what plants and other foods would help with sickness or heal wounds. Sap from the black boy tree was good for healing sores and was used as a soap. They also boiled it in water to make a varnish for painting.

When someone had the flu, they would kill a possum, boil it up in water and drink the water. A farmer once told me that possums taste terrible because they eat a lot of eucalyptus. He said the best way to eat possum is to boil it up with rocks, toss out the possum and eat the rocks. Seems like my family thought the same – unless people were sick. Then, all the eucalyptus oil was good for you.

Sometimes, it’s not obvious he makes the point he intends:

Once I was talking to a woman who believed the Stolen Generations are a myth. I’d been talking to her about the history of the Mundines and the land at Baryulgil and she was fascinated. So I told her about the time my grandfather Harry chased away the Welfare Board with a gun. She looked at me puzzled.

“But why would they take away the children from your families? They weren’t being neglected. You said the parents were hard workers and the children were well cared for,” she said.

“Define neglect,” I replied. “They lived in tin and bark sheds with dirt floors. Ate from the bush. Washed in the river. And Dad slept every night outside on the ground.”

I’m sympathetic to dramatically different lifestyles — like Comanche lives — and strongly err on keeping kids with parents. But is a government policy and social outlook that considers it neglectful to have children living in tin and bark sheds with dirt floors, eating from the bush and washing in the river so obviously barbaric?

A tone of proud self-reliance permeates Mundine’s story, which forms the backbone of his conservative outlook:

The Baryulgil families didn’t get any rations or supplies from the government or the missions. They took care of everything themselves – finding their own food and water, and building their own shelters. They would hunt, fish and collect their own food from the rivers and the bush and cook it on an open fire. They washed in the river and the waterholes.

He recalls a time when this posture was widespread. One indigenous man started a newspaper in 1938 called The Abo Call, describing it as "The voice of the Aborigines":

Its first edition reprinted the statement delivered to Prime Minister Lyons in full and opened with the following:

To all Aborigines! "The Abo Call" is our own paper.

It has been established to present the case for Aborigines, from the point of view of the Aborigines themselves. This paper has nothing to do with missionaries, or anthropologists, or with anybody who looks down on Aborigines as an "Inferior" race.

We are NOT an inferior race, we have merely been refused the chance of education that whites receive. "The Abo Call" will show that we do not want to go back to the Stone Age.

Representing 60,000 Full Bloods and 20,000 Halfcastes in Australia, we raise our voice to ask for education, Equal Opportunity, and Full Citizen Rights.

Much water has flowed since Aboriginal enfranchisement, and the hope of earlier Aboriginal pioneers has stagnated, settling into a perpetual victimhood narrative that Mundine loathes:

This narrative of Australia as a racist society doesn't hold back these people who peddle it. But it's incredibly damaging to Aboriginal people still living in disadvantaged families and communities — where kids don't go to school, where adults aren't working, where people are stuck in chronic intergenerational welfare dependence or living in dysfunctional environments ravaged by alcohol or substance abuse or violence, where young people think going to jail is a rite of passage or better than living at home. Racism is not the cause of these problems. Not any more. And when Aboriginal people hear the message that racism is to blame for their problems, it's paralysing.

He is scathing of the activist class that ignore the endemic abuse plaguing indigenous communities. The sexual abuse of Aboriginal children. The beating of wives.4 This is one of the darkest realities of modern Australia and Mundine does not shy away from it. Report after report show the same thing:

The Little Children Are Sacred report was publicly released in June 2007, outlining the findings of a review into the extent, nature and factors contributing to sexual abuse of Aboriginal children in the Northern Territory.

It found what so many other inquiries - both before and since - have found: that the sexual abuse of Aboriginal children is endemic and in the Northern Territory had reached such crisis levels that it should be designated "an issue of urgent national significance" by both the Australian and Territory governments.

The report was shocking, yet not surprising… There were three other significant reports, in the decade before, with similar findings about communities in New South Wales, Western Australia and Queensland - the Breaking the Silence report (2006), the Gordon Report (2002) and the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Women's Task Force on Violence Report (1999). In 2016, the Smallbone Report5 shocked a nation - again - revealing the miserable life of children in two Queensland Aboriginal communities and the absence of parental care and law enforcement. Even more outrageous was that the Queensland government sat on that report for three years because community leaders asked that it remain secret.

All of these reports paint a common picture - Aboriginal children exposed to some of the worst forms of sexual assault, psychological abuse and neglect imaginable, living in the grip of dysfunction, abuse, family violence and addiction. Sex offences well above the national average; sexual activity becoming normalised for young children. Police not trusted. Community leaders turning a blind eye. People failing to intervene in known cases of abuse or when witnessing abuse, fearing reprisals.

The reports are just the tip of an iceberg, as anyone knows who has spent time in Aboriginal communities suffering from social breakdown and dysfunction. Another related problem is the epidemic of family violence in the Aboriginal population, particularly affecting Aboriginal women, who are more than thirty times more likely to be hospitalised as a result of family violence and ten times more likely to die from a violent assault than other Australian women.

Mundine considers the Howard Government’s Intervention in Aboriginal towns — a heavy-handed attempt to curb abuse and violence — a failure, but a fair and honest attempt. In 2018 when Mundine published his memoir he was against the Voice — a current constitutional referendum to insert an indigenous advisory body to Parliament. He’s been a loud opponent to it in the current discourse. He does favour a Treaty though, and claims he convinced Tony Abbott of its merits too. He does not explain either position (except that he expected it to fail), although he has written at length (compellingly) about his opposition to the Voice since.6 He’s proud of helping to instigate the Closing the Gap annual report, which finally forces governments to measure indigenous outcomes. Unfortunately it shows what everyone knows: all those decades and billions have made no impact.

Mundine finds the attitude of the activist and academic class that patronise indigenous Australians as Forever Victims to be the real race essentialists. He resents the lack of individuality in this approach, as though Australian Aboriginals can only be viewed as a homogenous group:

It's founded on the idea black people are inferior, a group to be pitied, not individuals who choose their own path.

This is refreshing and optimistic: a belief in individual agency, of the breadth of human experience, and the promise in each person. And that goes for Aboriginal Australians as much as anyone else.

In one small but poignant marital moment, Mundine wrote fictional vignettes portraying stories from traditional Aboriginal songlines for the benefit of an Aboriginal dance troop he was leading. His then-wife was appalled. Dejected, he binned them.

Up to at least the 1950s, Koreans used human fertilizer for their fields. From T. R. Fehrenbach’s This Kind of War: The Classic Military History of the Korean War:

He never got used to the stink. Inside the city, the odors were of decaying fish, woodsmoke, garbage, and unwashed humanity. Outside, the fresh air was worse. Koreans, like most Orientals, use human fertilizer. Their fields and paddies, their whole country smells somewhat like the bathroom of a fraternity house on Sunday morning.

Clothing washed in their rivers turns a sickly brown.

China too. When he meets with the Chinese as part of a delegation he asks them not to nuke Australia and whether he can visit Tibet. He roguish style impresses the official and his request is granted — to visit Tibet. Nuking Australia is TBD.

In September 2016, the Northern Territory Police Commissioner said his officers responded to 75,000 cases of domestic violence in the previous three years.

The Smallbones report makes for grim reading. 82 cases of reported STIs for the period 2001 - 2012 involved children under 10 (0.4% of cases).

I am saving a deep dive into the Voice for another kvetch.

Misha, This is a beautifully-crafted distillation of the man who is Warren Mundine. I always thought you were a competent writer, but now I see your journalistic talent is supercharged by your perspicacity. Please keep up the great work!

Fascinating from an outsiders perspective. Is your sense that the rhetoric is more or less rancorous than race relations in the US?