We are made to live like firemen

Nassim Taleb's Fooled by Randomness and the games we play

I wish I had read Fooled by Randomness 15 years ago. It would have front-run many of my observations working in finance. And the unabashed tenor of it. Nassim Taleb wraps his message up in his personae. He is a deliberate and provocative outsider. He looks upon the smooth-brained smooth-talking banker with the puffed out chest and his nice house, never having been molested by an original thought or an ounce of curiosity, and he pities him, is revolted by him. Taleb treads outside these circles so as not to become them. He does not read or watch news. He wanders alone, outside the status games of Manhattan, for he knows he is but a man and men become the water they swim in.

There is something deeply resonant about Taleb’s world view. Like meeting a long lost relative. Or a preacher who has finally let you in on the joke.

It’s an intimate book. He’s letting you in on a secret. You’re not mad. He says. They’re all f*cking bonkers.

“Journalism may be the greatest plague we face today” - Nassim Taleb

Fooled by Randomness is not a finance book or a book aimed at investors, but its lessons bite sharpest there: the examples used are more often from finance land due to Taleb’s option trading background. For example:

We tend to think that traders were successful because they are good. Perhaps we have turned the causality on its head; we consider them good just because they make money.

We see the success stories and attribute the success to them, but Taleb shows how

a population entirely composed of bad managers will produce a small amount of great track records.

We only see that small minority (2% in Taleb’s example). Yet the other 98% are largely invisible. This asymmetry, this tendency for us to be fooled by randomness, rules everything around us. From history, to careers, to however we tell the narrative of our lives.

One final quote before diving into this week’s Kvetch. I will probably not be putting this to my investment colleagues:

My lesson from Soros is to start every meeting at my boutique by convincing everyone that we are a bunch of idiots who know nothing and are mistake-prone, but happen to be endowed with the rare privilege of knowing it.

In this Kvetch:

Harvard — what is broken with you?

The Cadence of the Thing

Kids: decades long feedback loops

Madness of modernity

Treadmills and ladders

Wax in ears and the binding of Isaac

We are made to live like firemen

1. Harvard — what is broken with you?

A friend of mine just finished his Harvard executive MBA. I want to recount a story he told me.

In one of their final classes, a Big Wig guest lecturer came in. He’d seen things. In the twilight of his career, he had reflected. He had repented. This class would be different.

He read out four eulogies to the class.

This, he said, is how people remember their lives. Not the sales they made, the meetings they attended, the brand names they accumulated along the way.

He asked the class to write a letter expressing gratitude — then and there — to someone who meant something to them. A parent, a friend, a spouse.

The class wrote as instructed.

After a time, he selected a student at random.

Who did you write to?

My mother.

I want you to call your mother right now and read out your letter to her.

In class, on loud speaker.

Abashed but bold — she was, after all, a Harvard Student — she did as instructed. The caller cried. Her mum cried. The class cried.

The professor then selected two others. More calls. More gratitude. More tears.

After this was done, he turned to the class.

You just paid $100,000 to learn to be grateful. What is broken with you?

We’ve used up half the allocated time. Get out. Go do something useful with yourselves.

My friend — a good man — told me this story with a kind of reflective awe.

Men will literally pay $X00k to Harvard instead of going to therapy. Bundled in the blue chip status purchase of Harvard now comes Mid-life Crisis Enlightenment and Self-Abasement. One stop shop for all Elite Marker needs.

Taleb in Fooled by Randomness writes:

surprisingly, MBAs, in spite of the insults, represent a significant portion of my readership, simply because they think that my ideas apply to other MBAs and not to them

What is broken with you?

It’s unclear to me whether the lecturer meant this literally or as a sort of parable. Like the Wizard of Oz reveal — there’s nothing here! It was about the friends you made along the way. Or something. Presumably the point isn’t that they’re actually broken (read: idiots?). That’s a bit on the nose for Harvard MBAs I would have thought. But who knows, maybe it’s just all the other Harvard MBAs.

2. The Cadence of the Thing

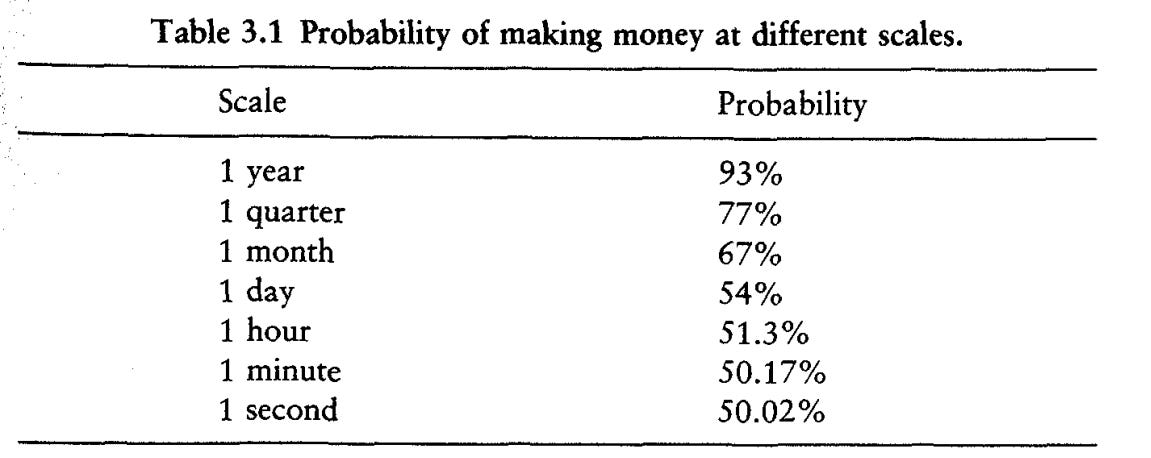

In Fooled By Randomness, Taleb manufactures a trader who follows a strategy that will generate an expected return 15% above the risk free rate, with a 10% error rate per annum.

The same trader will experience life very differently purely depending on how often they check in on their portfolio. A trader who checks in every moment or every day will have roughly half good moments and half bad (flip a coin!) yet over a year the vast majority will be good:

Now consider the average company board meeting. It probably happens monthly (a smaller company or startup might do it quarterly).

I was struck by this very phenomenon when I was involved with (let’s call it) Mining Services Co.

Mining Services Co could expect to be awarded a major contract roughly every quarter. With a monthly board cadence, this meant meetings in month 1 and month 2 of the quarter could be stressful — cash in the form of capital investment (and maybe operating losses) is going out, and no new contracts are coming in. It sure doesn’t feel like things are going to plan in those moments. Even if you are doing the exact right thing, in those moments success looks exactly the same as failure.

This is exacerbated with longer sales cycles. In enterprise sales, this can be 9 — 12 months (or longer!) where success looks the same as failure. (Of course the inverse is also true: in consumer or small business sales, where you are reliant on hundreds or thousands or more transactions or contracts every day or month, you get very fine feedback loops).

Long sales cycles with steady losses or investment in between look an awful lot like being “long volatility”. Per Taleb:

It requires some strength of character to accept the expectation of bleeding a little, losing pennies on a steady basis even if the strategy is bound to be profitable over longer periods. I noticed that very few option traders can maintain what I call a “long volatility” position, namely a position that will most likely lose a small quantity of money at expiration, but is expected to make money in the long run because of occasional spurts.

One can buy, say, an oil & gas exposed asset around the bottom of the market and bet exactly that it’s likely to bleed a bit for a few years, but that should a demand or price surge come (and you may have good reason to expect it will), you will make out like a bandit. You can write in your investment memo that there is a universe where this does not happen over your investment horizon. And your investment committee may nod and accept that risk, because it really looks like on balance you’ll make out like a bandit (and you might even be able to sell the business for equipment value if this does not eventuate). It sounds so neat, so clever in theory — and it may be a good bet and work out well. But to actually live that yearly, month, weekly, daily bleed takes a special love of pain.

3. Kids: decades long feedback loops

Kids have some of the longest feedback loops of all.

You probably aspire to measure your relationship with your kids over decades. You want them to be well now, to love you, to have friends. But you also want them to graduate from school, avoid a meth addiction, invite you to their wedding and give you grandkids. I have three kids under 6 and I have ~zero feedback loops for things I do today with respect to those outcomes (and a gazillion more).

When I had my first kid I felt a strange sense like I was kicking off a stop watch I couldn’t stop. I had planted a seed that would grow into an oak — I had only to let time pass and not break it. This visceral sense of a new interminable cycle beginning led me fairly directly to have two more in fairly quick succession (no reason, all rhyme). There was this atavistic sense that now that I had begun the timer, the cycles were so long I needed to get on with the rest. A vague sense that my future self in 5 or 10 or 30 years would be grateful.1

Kids are also going “long volatility”. Time and money only go one way for a long time (forever?). Yet…. that’s probably a bit too cute. It’s not like there aren’t intermittent payoffs. In fact, the payoffs are daily. When I picked up my eldest daughter this morning and kissed her and danced with her for a moment — just this one, small moment — that was a visceral feedback loop, an immediate hit of dopamine and holiness. My kingdom for one such moment. And they are daily — many times a day even.

Culture also guides you with strange long-ago-forged nudges to get you over blind spots. You don’t know you want grandkids when you’re 20. The challenge is you’ll want them in 30 — 40 years. Tell that to a 20 year old and he may have trouble hearing you over the cacophonic need to fight and f*ck. So how do you set the right behavioral cadence for that? What can bridge decades long blind spots? Cultural norms to marry and bear children. The payoff will come.

4. Madness of modernity

We do not need to be rational in our inner lives, only external threats.

Modernity demands the opposite of us:

Our human nature dictates a need for péché mignon. Even the economists, who usually find completely abstruse ways to escape reality, are starting to understand that what makes us tick is not necessarily the calculating accountant in us. We do not need to be rational and scientific when it comes to the details of our daily life—only in those that can harm us and threaten our survival. Modern life seems to invite us to do the exact opposite; become extremely realistic and intellectual when it comes to such matters as religion and personal behavior, yet as irrational as possible when it comes to matters ruled by randomness (say, portfolio or real estate investments). I have encountered colleagues, “rational,” no nonsense people, who do not understand why I cherish the poetry of Baudelaire and Saint-John Perse or obscure (and often impenetrable) writers like Elias Canetti, J. L. Borges, or Walter Benjamin. Yet they get sucked into listening to the “analyses” of a television “guru,” or into buying the stock of a company they know absolutely nothing about, based on tips by neighbors who drive expensive cars.

Steven Levitt had a great conversation with Russ Roberts on EconTalk in 2020 that stuck with me:

Steven Levitt: I've sat in meetings where 10 faculty members who, combined have an outside wage option of, you know, I don't know, $15,000 an hour--have sat for an hour arguing about how to allocate $250 worth of stuff. And, at the end, I finally said, 'Look--'

Russ Roberts: Flip a coin--!

Steven Levitt: This is my answer to everything. 'I'll just write you a check for $250, and one side can have it, the other side can have it. This makes no sense. Why are we sitting here doing this?'

What’s going on here?

My guess is that this isn’t just dumb. My guess is there is something else going on. Levitt gave another example in the same interview where a preeminent economist refused to offer tenure to someone who, it was unanimously agreed, deserved it based on their work to date. Yet the economist said that person wasn’t ready.

So what’s going on?

There are similar examples I could give from countless meetings where it took me a long time to realise that what was really going on was not the ostensible purpose of the meeting (what a naïve participant might call truth seeking of one kind or another). It was something else entirely. And not quite in the hidden meaning sense, like this classic clip from Annie Hall:

Rather, there is a kind of meta dance. Social jostling. Assertions of dominance. Testing, parrying.

These are atavistic human games. I don’t know Levitt’s professor, but it sure sounds like a human hierarchy game. Some mix of control and status management.

I suppose this argument isn’t all too different to what Kahneman and Taleb attribute to our monkey brains. Math and reasoning are not only counterintuitive but also a new way of thinking.

In Joseph Henrich’s excellent The WEIRDest People in the World, WEIRD people (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic) are distinguished from other cultures today and ~all cultures in the past by being more fixated on abstractions and reasoning over relationships.

Mediating reality through relationships is our historic default. In our daily interactions with people working towards a solution (get a coffee, console an upset spouse, consider an investment decision), the solving part is only a part of the interaction. Some portion (a lot of it?) is animalistic relationship management, with all the hierarchy and bum sniffing involved.

5. Treadmills and ladders

Taleb describes the misery successful people inflict on themselves. One such example is self-selecting to islands of uber success. Which has the perverse effect of making you feel unsuccessful.

As compared to the general U.S. population, Marc has done very well, better than 99.5% of his compatriots. As compared to his high school friends, he did extremely well, a fact that he could have verified had he had time to attend the periodic reunions, and he would come at the top. As compared to the other people at Harvard, he did better than 90% of them (financially, of course). As compared to his law school comrades at Yale, he did better than 60% of them. But as compared to his co-op neighbors, he is at the bottom!

I’d generalise this further.

The more of an outlier you are in any respect (money, intelligence, beauty, chess, archery, whatever), the larger the gaps between you and the next best above and below. If you are of median wealth, well, so are many others (by definition). Good chance that in your milieu the differences are slight. 68% of folks live within one standard deviation of the mean, in that hill at the center of the bull curve. Now let’s move to the right. The gaps between the richest and the best become enormous. There are, by definition, very few at the far right distribution. Let’s take the richest people on earth. This fluctuates, but according to the latest Forbes list the difference in wealth between #1 and #100 is US$200bn. The difference between #100 and #200 is about US$7bn. There are literally hundreds of blokes with US$1.0bn flat. The closer you move to the average, the more crowded it is.

Someone recently told me: the way to make someone worth $X00m feel poor is to put them in a room of billionaires.

Reminds me of this Kerry Packer story.

Packer, the late Australian billionaire casino mogul, was playing at a Vegas table when a brash Texan asked to join. Packer wanted to be left alone.

“I’m a big player too. I’m worth $100 million,” said the Texan.

At which point Packer produced a coin from his pocket and said, “I’ll flip you for it.”

This doesn’t just apply to money. Obsessed with WWII? Bitcoin? F1? Knitting? If you’re in the top 1% of something, you’ll notice the people who are really into that thing. Like 100x into it. You might appear like you’re into it to a layperson, and you might be, but you’ll increasingly feel like a schmuck because you’re in a unique position — you’re also in the top 1% of people who can appreciate all these people who are exponentially more into it than you.

I’m an okay swimmer and cyclist. When I ran a triathlon earlier this year I did it in 2 hours and 40 min, which is about average for men in my age cohort. Middle of the pack! But that’s of men who finish a triathlon. In the general population, what would it be? Top 5%?

So there is this strange effect that the better you get, the higher you climb, the more acutely you feel your inadequacy. When you’re hunting elephants, the elephants just get bigger.

6. Wax in ears and the binding of Isaac

We are spikey in our reason.

We are attuned to solving problems in our theoretical habitats, but those moments are islands in a sea of instinct, relationships, and atavistic gooey vibes.

Levitt’s committee of economists above is one such example.

Taleb on mathematicians:

Mathematicians tend to make egregious mathematical mistakes outside of their theoretical habitat. When Tversky and Kahneman sampled mathematical psychologists, some of whom were authors of statistical textbooks, they were puzzled by their errors. “Respondents put too much confidence in the result of small samples and their statistical judgment showed little sensitivity to sample size.” The puzzling aspect is that not only should they have known better, “they did know better.” And yet . . .

Taleb cites more: cancer doctors and nurses smoking outside their wards, probability experts as gambling degenerates. We are fallible emotional humans.

Taleb puts wax in his ears: he isn’t as wise as Odysseus who can bear the siren’s song, tied to the mast. He cannot ignore his emotions — he admits he’s as emotional if not more than us all. He is one of Odysseus’s hulking crew, eyes forward and wax eared. He assumes he will be seduced by his emotions and plans accordingly.

To me this brought to mind the binding of Isaac. The midrash tells us Abraham was 137 years old and Isaac 37 at the time. Abraham could not have bound Isaac involuntarily. And so the midrash tells of a tender moment. As Abraham takes his son up the mountain to be slaughtered according to God’s command, Isaac asks Abraham to be sure to bind him tight: he does not know how he will act in the moment the dagger falls. And he does not wish to derivate from his submission to God’s will.

Odysseus’s men put wax in their ears. Taleb absconds into solitude or imagines his interlocutors as aliens (for aliens do not provoke the same rivalry and rage of other men), and Isaac asks to be bound tight. How do you bind your future self to reason and to God’s will?

The story of Isaac is Talebian in another way. A joke wrapped in irony. The first angel to appear to man is the one who tells Abraham’s wife she is to bear a son. She laughs: at ninety, it sounds like a joke. So the first angel is a comedian.

Isaac’s name is then derived from the word “laughter”. And yet: he is a remarkably introspective, humourless man. Ironic. There’s also a kind of bit between God and Abraham:

7. We are made to live like firemen

I want to leave off on this extract from the epilogue of Fooled by Randomness. One of my favourite truffles of wisdom.

You can choose how to live.

I am convinced that we are not made for clear-cut, well delineated schedules. We are made to live like firemen, with downtime for lounging and meditating between calls, under the protection of protective uncertainty. Regrettably, some people might be involuntarily turned into optimizers, like a suburban child having his weekend minutes squeezed between karate, guitar lessons, and religious education. As I am writing these lines I am on a slow train in the Alps, comfortably shielded from traveling businesspersons. People around me are either students or retired persons, or those who do not have “important appointments,” hence not afraid of what they call wasted time. To go from Munich to Milan, I picked the seven-and-a-half-hour train instead of the plane, which no self-respecting businessperson would do on a weekday, and am enjoying an air unpolluted by persons squeezed by life.

I came to this conclusion when, about a decade ago, I stopped using an alarm clock. I still woke up around the same time, but I followed my own personal clock. A dozen minutes of fuzziness and variability in my schedule made a considerable difference. True, there are some activities that require such dependability that an alarm clock is necessary, but I am free to choose a profession where I am not a slave to external pressure. Living like this, one can also go to bed early and not optimize one’s schedule by squeezing every minute out of one’s evening. At the limit, you can decide whether to be (relatively) poor, but free of your time, or rich but as dependent as a slave.

As seductive as this rousing call to freedom is, I must temper it with one observation. This works for a man after his kids are of a certain age. Before he has kids he is making something of himself. When he has kids the pull is to the opposite: you are bound not by the alarm of the clock but the schedules of your babies and your need to provide for them. With kids, you cannot escape community: you are bound to those around you even tighter, so you must select that community carefully. For, as Taleb warns, you will become them. Although his warning may be applied to children too: to allow boredom to ooze in between the cracks of an over-optimised schedule.

With this in mind, I narrow his injunction: do not allow yourself to be enslaved by a past routine and a dull mind. Press on for freedom once more when you can.

Or is this just my excuse as a parent to plough on, bound to my alarm clock, a slave addicted to his chains?

I am speaking here in the first person singular — but of course my wife and I chose to have those kids together. I am speaking here only for my personal experience, you will have to ask her for hers.

"There is something deeply intellectually and emotionally resonant about Taleb’s world view."

Then you read his Twitter feed.

Misha! I've been meaning to read Kvetch since I saw you in the comments of In My Tribe a couple of weeks back. Arnold Kling quoted today from your section "Kids: decades long feedback loops" which really resonated and motivated me to read your full post. The phenomenon you describe in the "Treadmills and ladders" section is something I'm thinking a lot about at the moment (it is basically the conversation I had with my wife last night). You articulate the phenomenon well. Understanding the phenomenon hasn't resolved my mindset unfortunately!