Wife economics and the Domestication of Man (Part II)

The Church enforces monogamy and the beauty and brutality of Comanche life

This is Part II of this series. You should at least read the preamble of Part I before continuing.

"They scalped her alive by making deep cuts below her ears and peeling the top of her head entirely off”

Man is born polygamous

The Lakotas

Part II (this Kvetch):

The Church destroyed polygamy and spurred innovation

When Christian men go native

The Comanches

Slavery and polygamy: collapse of twin institutions

White Squaws and life under the stars

Bride inflation, Tinder and modern dating

Polygamy in Judaism (or, Love in the Time of Gomorrah)

3. The Church destroyed polygamy and spurred innovation

Adolescent men begin life as wolves. The energy and danger in young adolescent men is ancient. As Razib Khan wrote on men, violence and the wolf in a Eurasian context:

Their potential to coalesce into a powerfully disciplined, loyal and hierarchical pack is undeniable. But until they are fully tamed, trained and their wild impulses fully curbed, they are for all intents and purposes as actual wolves in the midst of society’s hen house. Little wonder then that pastoralist societies conventionally exiled them en masse as far from the center of civilization as possible until that developmental period of peak danger safely passed. Or that they referred to them as dogs and wolves. Often the greatest threat to the stability of society was literally in its midst. Male adolescence was… an inexhaustible reservoir of dogs.

If they enter a polygamous society, one important status game young men will play is wife accumulation.

If they enter a monogamous society, that energy goes elsewhere. In order to be domesticated into monogamy, these wolves must be sedated. Marriage tranquilises men and puts them to productive use providing for children:

The consequence is that WEIRD marriage, which of course was built out of Christian marriage, generates a peculiar endocrinology. It’s widely believed by physicians that testosterone “naturally” declines as men age. In the 21st-century United States, these drops are so severe that some middle aged men are treated medically for low-T. But, as I’ve explained, across societies possessing more human-typical marriage institutions we don’t see these declines as often, and when we do, they aren’t nearly as steep as in WEIRD societies. It seems that a WEIRD endocrinology accompanies our WEIRD psychology.

The Church domesticated men:

…the Church, through its centuries-long struggle to disseminate and enforce its peculiar version of monogamous marriage, unintentionally created an environment that gradually domesticated men, making many of us less competitive, impulsive, and risk-prone while at the same time favoring positive-sum perceptions of the world and a greater willingness to team up with strangers. Ceteris paribus, this should result in more harmonious organizations, less crime, and fewer social disruptions.

Domesticated men — via monogamous marriage and the corresponding decline in testosterone — commit less crime. It’s not that more docile men get married. They become wolves again after a marriage dissolves:

Strikingly, not only did a man’s likelihood of committing a crime go up after a divorce—when he became single again—but it also increased after his wife passed away. Numerous other studies support the view that getting married in a monogamous society reduces a man’s likelihood of both committing crimes and abusing alcohol or drugs.

Men in polygamous societies are always on the look out for more wives, so they retain elevated testosterone levels and virility. No wonder some Comanche had such glorious names as “Erection-That-Won’t-Go-Down” (a real example — more on the Comanches later).

The Church took away your slave girls (in a break from its Hebrew forefathers — discussed in detail in a later Part to this series):

Christian monogamy was a particularly potent package for suppressing T levels. Besides limiting men to one wife, the Church’s MFP [marriage and family programme] included several other active ingredients. First, it constrained men from seeking sex outside of marriage—from visiting prostitutes or having mistresses. To accomplish this, the Church worked to end prostitution and sexual slavery while creating social norms that motivated communities to monitor men’s sexual behavior and make violations public. God, of course, was enlisted to monitor and punish the sexual transgressions of both men and women, which fueled the development of Christian notions of sin and guilt. Second, the Church made divorce difficult and remarriage close to impossible, which prevented men from engaging in serial monogamy. In fact, under the Church’s program, the only way anyone could legitimately have sex was with one’s spouse for procreation

The Church enforced monogamous marriage, banning polygamy and incest and also cracking down on divorce:

If you can’t add wives to your household via polygyny, perhaps you can divorce and remarry a younger wife in hopes of producing an heir? No, the Church shut this down, too. In 673 CE, for example, the Synod of Hertford decreed that, even after a legitimate divorce, remarriage was impossible. Surprisingly, even kings were not immune from such prohibitions. In the mid-ninth century, when the king of Lothringia sent his first wife away and took his concubine as his primary wife, two successive popes waged a decade-long campaign to bring him back into line. After repeated entreaties, synods, and threats of excommunication, the king finally caved in and traveled to Rome to ask for forgiveness. These papal skirmishes continued through the Middle Ages. Finally, in the 16th century, King Henry VIII turned England Protestant in response to such papal stubbornness.

I wrote about Henry VIII’s chutzpah here. Another fun example:

In the 11th century, for example, when the Duke of Normandy married a distant cousin from Flanders, the pope promptly excommunicated them both. To get their excommunications lifted, or risk anathema, each constructed a beautiful abbey for the Church. The pope’s power is impressive here, since this duke was no delicate flower; he would later become William the Conqueror (of England).

These policies destroyed Europe’s intensive kin-based institutions:

The Church’s constraints on adoption, polygamy, and remarriage meant that lineages would eventually find themselves without heirs and die out. Under these constraints, many European dynasties died out for the lack of an heir.

The Church inherited their land and became the largest landowner in Europe:

By 900 CE, the Church owned about a third of the cultivated land in western Europe, including in Germany (35 percent) and France (44 percent). By the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, the Church owned half of Germany, and between one-quarter and one-third of England.

Pre-modern Mexicans lived similarly. For example (from Fire and Blood: A History of Mexico):

Nezahualcóyotl did live the good life of a Mexic prince. He enjoyed his splendid apartments and great library and the services of a vast harem. He sired over a hundred children by these wives and concubines.

After the Spanish conquest, there too it was the men of the Church who led the charge:

The friars had a great problem with native sexuality, especially the custom of Mexic chiefs to take multiple concubines and wives.

Anyway, the incredible effect of all this is to restrict elite men:

Monogamous marriage changes men psychologically, even hormonally, and has downstream effects on societies. Although this form of marriage is neither “natural” nor “normal” for human societies—and runs directly counter to the strong inclinations of high-status or elite men—it nevertheless can give religious groups and societies an advantage in intergroup competition. By suppressing male-male competition and altering family structure, monogamous marriage shifts men’s psychology in ways that tend to reduce crime, violence, and zero-sum thinking while promoting broader trust, long-term investments, and steady economic accumulation. Rather than pursuing impulsive or risky behaviors aimed at catapulting themselves up the social ladder, low-status men in monogamous societies have a chance to marry, have children, and invest in the future. High-status men can and will still compete for status, but the currency of that competition can no longer involve the accumulation of wives or concubines. In a monogamous world, zero-sum competition is relatively less important. So, there’s greater scope for forming voluntary organizations and teams that then compete at the group level.

Why do I say incredible? It seems far from trivial for a society to develop norms and institutions that restrain their most violent, capable and successful members. Which explains why monogamy is relatively rare across societies in history.

Monogamous marriage fuels innovation by breaking clan ties:

Many of preindustrial Europe’s unusual norms related to marriage and the family would have lowered women’s fertility and reduced population growth. First, based on contemporary research, both the imposition of monogamous marriage and the ending of arranged marriages would have lowered the total number of babies a woman had in her lifetime. This happens because these norms raise the age at which women marry (shrinking the window for pregnancies) and increase their power within the marriage, both of which reduce women’s fertility. Second, the MFP favored neolocal residence and generated high rates of mobility for young people (they were no longer tied down by kin obligations). In general, anything that separates a woman from her blood or affinal relatives lowers her fertility, because she has less support in childcare and will experience less pressure from nosy relatives to get pregnant. Third, unlike other complex societies, many European women never married or had children—the Church created a way for women to escape marriage pressure by entering the sisterhood (the nunnery). Finally, formal schooling for girls—promoted by Protestantism—generally lowers fertility. This happens for several reasons, but one is simply that schooling allows women to avoid early marriage to finish their education. Now, European populations did grow in response to economic prosperity after 1500, but kin-based institutions and marriage norms constrained that expansion and shifted it into cities (via migration). In short, the demolition of kin-based institutions in Europe helped spring the Malthusian Trap by fueling innovation while simultaneously suppressing fertility.

This is where I repeat Caroline Ellison’s post on the trade off between social bonds and world conquest:

4. When Christian men go native

There are some colourful examples of what men get up to when adventuring far from their wives and Christian mores. They go native.

This Scotsman spoke fluent Zulu and earned a fortune from cattle loans & trophy hunts. He had 49 wives (1 Eurasian & 48 Zulu) & 117 children.

This Englishman took thirteen Indian wives and every evening he’d take all thirteen of his wives on a promenade around the walls of the Red Fort, each on the back of her own elephant.

Niall Ferguson notes a few more examples in India (from Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World):

John Maxwell, a minister’s son from New Machar near Aberdeen who became editor of the India Gazette, was no less intrigued by the (to his eyes) luxurious and effeminate ways of Indian life: he had at least three children by Indian women. William Fraser, one of five brothers from Inverness who came to India in the early 1800s, played a crucial part in subjugating the Ghurkas; he collected both Mughal manuscripts and Indian wives. According to one account, he had six or seven of the latter and numberless children, who were ‘Hindus and Muslims according to the religion and caste of their mamas’. Among the products of such unions was Fraser’s friend and comrade-in-arms James Skinner, the son of a Scotsman from Montrose and a Rajput princess, and the founder of the cavalry regiment Skinner’s Horse. Skinner had at least seven wives and was credited with siring eighty children: ‘Black or white will not make much difference before His presence’, he once remarked. Though he dressed his men in scarlet turbans, silver-edged girdles and bright yellow tunics and wrote his memoirs in Persian, Skinner was a devout Christian who erected one of the most splendid churches in Delhi.

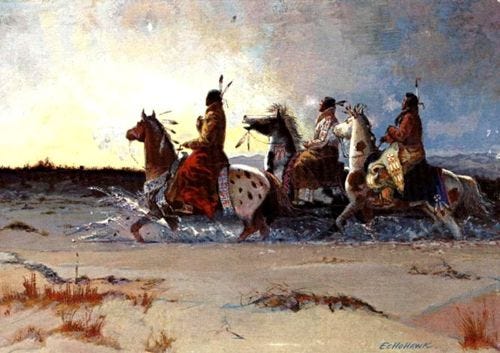

5. The Comanches

In The Comanche Empire Pekka Hämäläinen echoes his findings with the Lakotas (discussed in Part I). Polygamy became distended with the increasing labour value of wives:

Polygyny, a marriage system in which men have several wives, was traditional among the Comanches, but the practice expanded dramatically under the pressures of escalating market production, which put a premium on women’s work. Hunting, raiding, and horse breeding, the main production activities of men, stressed daring and risk-taking, whereas the female activities of robe dressing, meat processing, and horse herding emphasized manual labor. Since a man could procure horses and robes faster and with less effort than a woman could feed, tend, and process them, men began to seek multiple wives to enlarge their labor pool. Polygyny became widespread by the turn of the eighteenth century and expanded steadily thereafter.

Polygyny was the primary means for mobilizing the female labor force for expanding market and domestic production.

The expansion of polygyny also enhanced men’s control over the marriage institution itself. In the early nineteenth century, many marriages were arranged by the father or brother of the bride, who often could not refuse the selected husband… Besides altering marriage from an emotional bond more toward an economic investment, polygyny had several adverse practical effects on the female population. As the demand for female labor increased, girls were married younger, frequently before they reached puberty. Many Comanche parents tried to marry several of their daughters to the same man, thereby hoping to pressure the son-in-law to treat them better, but the downside of the practice was that marriage contracts were often made when the girls were still in their early teens.

Women wielded softer forms of power, yet the escalation of polygamy worked against them:

[W]hite observers rarely wrote about the more veiled domestic sphere where women exerted considerable moral authority. In the lodge, beyond Euro-American gaze, women were the principal decision makers. Paraibooʔs, senior first wives, controlled the distribution of food and commanded secondary wives and slaves, enjoying the privileges of wealth… Women directed child rearing, owned packhorses, and could trade a small portion of the robes and meat they produced for the market. Women in sororal polygynous marriages found emotional support among their sisters, and women who were married to abusive or underachieving husbands frequently ran off with lovers or neglected household duties until their husbands divorced them. And yet the overarching theme of contemporary observations—that the escalation of polygyny had a negative effect on women’s status—is unquestionably true. The countless secondary wives of polygynous marriages formed a new exploited underclass of servile laborers in the Comanche society that was gearing its very foundation around market-driven surplus production.

6. Slavery and polygamy: collapse of twin institutions

The Comanches became the largest slaveholders in the Southwest. It’s a nice example of the symbiotic relationship between slavery and polygamy:

The escalation of polygyny went hand in hand with the escalation of slavery. The two institutions had a common genesis—both developed to offset chronic labor shortages arising from market production—and they were functionally linked: many female slaves were eventually incorporated into Comanche families as wife-laborers.

Comanches had raided other Native societies for captives long before European contact, and they became in the early eighteenth century the dominant slave traffickers of the lower midcontinent. It was not until after 1800, however, that human bondage became a large-scale institution in Comanchería itself. Comanches conducted frequent slave raids into Texas and northern Mexico during the second and third decades of the new century and soon emerged as the paramount slaveholders in the Southwest.

In 1850, for example, a New Mexican from San Miguel del Vado reported of his visit to a western Comanche ranchería where “there were almost as many Mexican slaves, women and children, as Indians.” That report was echoed by George Bent, who knew Plains Indian cultures intimately and who recalled that “nearly every family” among the Comanches “had one or two Mexican captives.”

Slavery is up there with polygamy as one of the oldest, most enduring institutions of human civilisation, only recently having been vanquished. Pre-dating even written records, slavery has been near-universal and natural to man as far back as we can see. It’s ubiquitous in the Hebrew Bible (as I discuss in a future Part). In the same way it is natural for powerful men to collect wives so is it natural for them to subjugate captives. That we constrained elite men from these primal urges is remarkable, even shocking (try saying this at a party: I still can’t believe we abolished slavery).

Of course, forms of both slavery and polygamy continue to lurk in the shadows.

Interesting to compare the two in another way. Which came first, the social technology or material technology? Slavery may offer a clue. Why did slavery disappear when it did? Arguably, it was exactly when it could. When sails and manual ploughs were displaced by the turbine. Perhaps marriage follows a similar trajectory? Were there technologies that allowed the Church to enforce monogamy when it did? Henrich’s story is very much about monogamy unleashing technological growth, but curious what the case might be for technological growth unleashing monogamy.

7. White Squaws and life under the stars

How might we consider life for Comanche women in a world of polygamy and slavery? One hint lies with white captives who were subsequently freed. It’s hard to be definitive — there are just a few examples — but their stories are striking.

The story of Cynthia Ann Parker was once known to every child in Texas (from Empire of the Summer Moon):

In 1836, at the age of nine, she had been kidnapped in a Comanche raid at Parker’s Fort, ninety miles south of present Dallas. She soon forgot her mother tongue, learned Indian ways, and became a full member of the tribe. She married Peta Nocona, a prominent war chief, and had three children by him, of whom Quanah was the eldest. In 1860, when Quanah was twelve, Cynthia Ann was recaptured during an attack by Texas Rangers on her village, during which everyone but her and her infant daughter, Prairie Flower, were killed.

Another captive was Bianca “Banc” Babb, kidnapped by Comanches at the age of ten in September 1866 in Decatur (northwest of present-day Dallas):

Her mother was stabbed four times with a butcher knife while Banc held her hand. Then the little girl watched as her mother was shot through the lungs with an arrow and scalped while still alive. (She was later found with her blood-smeared baby daughter, who was trying to nurse at her dying mother’s breast.) Banc also watched as Sarah Luster, a beautiful twenty-six-year-old who was captured with her, became, in Banc’s brother’s words, “the helpless victim of unspeakable violation, humiliation, and involuntary debasement.”… At one point Banc was given a chunk of bloody meat cut from a cow that wolves had killed. She ate it, and liked it. She lost control of her bowels while on the back of the horse, and thus acquired her unfortunate Indian name: “Smells Bad When You Walk.”

Life wasn’t all bad. Despite the challenges and uncertainty of nomad life,

…she recalled that “every day seemed to be a holiday.” She played happily with other children. She loved the informality of meals that usually involved standing around a boiling kettle and spearing meat with skewers. She liked the taste of the meat, though she said it took a long time to chew. Tekwashana [her adopted mother] taught her to swim, pierced her ears, and gave her long silver earrings with silver chains and brass bracelets for her arms. The Comanche women mixed buffalo tallow and charcoal and rubbed it into her bright blond hair to make it dark. She loved the war dances. She learned the language quickly and so well that, after only seven months of captivity.

In April 1867, Banc was ransomed for $333. She escaped with her adopted mother but was tracked down and caught the next day. Banc was soon returned to her family. At their reunion, she realised that she had forgotten how to speak English.

Here is Minni Caudle’s story:

Like Banc, too, Minnie was held captive half a year, then ransomed and returned… As long as both of them lived, Banc and Minnie defended the Comanche tribe. Minnie Caudle “would not hear a word against the Indians,” according to her great-granddaughter. Her great grandson said, “She always took up for the Indians. She said they were good people in their way. When they got kicked around, they fought back.” This is asserted against the brute facts of her own experience, which involved watching her captors rape and kill five members of her family. Banc Babb, against all reason and memory, felt the same way. In 1897 she applied for official adoption into the Comanche tribe. Both girls had seen something in the primitive, low barbarian Comanches that almost no one else had, not even people like Rachel Plummer with long experience of tribal life. Banc’s brother Dot Babb described it as “bonds of affection almost as sacred as family ties. Their kindnesses to me had been lavish and unvarying, and my friendship and attachment in return were deep and sincere.” The children all had the sense that, at the core of these most notorious and brutal killers, there existed a deep and abiding tenderness. Perhaps that should be obvious, since they were, after all, human beings. But it was absolutely not obvious to white settlers on the western frontier in the mid-nineteenth century.

This is what life looked like for Cynthia Ann Parker (renamed Nautdah after her capture by the Comanches), which is a nice personal example of the portrait Hämäläinen painted of the hard, bloody work of Comanche and Lakota women (from Empire of the Summer Moon):

What Nautdah did was bloody, messy work. Sometimes she was covered from head to toe in buffalo fat, blood, marrow, and tissue, so much so that it turned her naturally light hair and light skin almost black. So much so that it would have been hard to spot her as the white woman in the Indian camp. While she worked, she watched her children. She was still nursing her daughter, Prairie Flower. Her boys played. They were old enough to hunt now, too, and sometimes they went out with their father. Peta Nocona, meanwhile, spent his time hunting and raiding.

This is what Ann Parker’s / Nautdah’s husband got up to:

On November 26 1860, a group of seventeen braves from Nocona’s force arrived at the Sherman home. The Shermans were having dinner at the time. The Indians entered the cabin, actually shook hands with the family, then asked for something to eat. The Shermans, nervous and unsure what was happening, gave the Indians their table. Once they had eaten, the Indians turned the family out, though with continuing professions of goodwill. “Vamoose,” they said. “No hurt, vamoose.”… Half a mile from their house, the Indians reappeared. Now they seized Martha, who was nine months pregnant… There she was gang-raped. When they were finished, they shot several arrows into her and then did something that was unusually cruel, even for them. They scalped her alive by making deep cuts below her ears and, in effect, peeling the top of her head entirely off. As she later explained, this was difficult for the Indians to do, and took a long time to accomplish. Bleeding, she managed to drag herself back inside her house, which the heavy rain had prevented the Indians from burning, where her husband found her. She lived four days, during which time she was coherent enough to tell the story to her neighbors. She gave birth to a stillborn infant… She was one of twenty-three people who died by the hand of Peta Nocona’s raiders over a span of two days.

The Texans eventually killed Nacona (in a typical massacre), where they found Ann Parker.

Leaving her people behind after the killing of her husband and losing her two sons broke Ann Parker more than her capture by the Comanches. She never spoke English again. She continued to worship in the Comanche manner. She tried to escape with her daughter. After her daughter died of the flu,

she became bitter over her enforced captivity, refused to eat, and eventually starved herself to death.

Cynthia Ann Parker found such meaning amongst the Comanches, who became her people and her family, that return to colonial society destroyed her soul and body.1

Despite slavery and polygamy, and the indisputable brutality of warfare on the frontier, it’s impossible to ignore how idyllic aspects of this life were. This is what they took from you:

As he learned to ride, the Comanche boy was initiated into the secrets of weaponry, usually by his grandfather or another elderly male. At six he was given a bow and blunt arrows and taught to shoot. He soon began hunting with real arrows, going out with other boys and shooting birds. In the Comanche culture boys were allowed extraordinary freedom. They did no menial labor of any kind. They did not fetch water or wood. They did not have to help pack or unpack during the band’s frequent moves. Instead they roved about in gangs, wrestling, swimming, racing their horses. They would often follow birds and insects, shooting hummingbirds with special headless arrows that had split foreshafts. They shot grasshoppers and ate the legs for lunch. Sometimes they tied two grasshoppers together with a short thread and then watched them try to jump. They would make bets. The first one that fell on its back was the loser. They occasionally played with girls. One co-ed game called Grizzly Bear consisted of a “bear” inside a circle who tried to capture children outside the circle who were protected by a “mother.” The children would run into the circle trying to steal some of the bear’s “sugar.” At night they listened to their elders tell terrifying stories of Piamempits, the Big Cannibal Owl, a mythological creature who dwelt in a cave in the Wichita Mountains and came out by night to eat naughty children.

This is not the only idyllic scene portrayed of Comanche life, but it struck me the most. Hämäläinen speaks of Ann Parker’s life under the stars and open plains — and it sounds nice — but I do worry about over-romanticising it. It also carries echoes of Apocalypto’s portrayal of native life.

Even accounting for the hard manual work done by Comanche women, we forget how hard life in the West was for a long time. One example, from around the time of the life of Ann Parker and the Comanches (from Energy and Civilization: A History by Vaclav Smil):

An Inquiry Into the Condition of the Women Who Carry Coals Under Ground in Scotland, Known by the Name of BEARERS

This was the title of the addition to A General View of the Coal Trade in Scotland, published in 1812; here are the key findings (Bald 1812, 131–132, 134):

“The mother … descends the pit with her older daughters, when each, having a basket of suitable form, lays it down, and into it the large coals are rolled; and such is the weight carried, that it frequently takes two men to lift the burden upon their backs … The mother sets out first, carrying a lighted candle in her teeth; the girls follow … with weary steps and slow, ascend the stairs, halting occasionally to draw breath. … It is no uncommon thing to see them, when ascending the pit, weeping most bitterly, from the excessive severity of labor. … The execution of work performed … in this way is beyond conception. … The weight of coals thus brought to the pit top by a woman in a day, amounts to 4080 pounds … and there have been frequent instances of two tons being carried.”

It’s worth wondering why portions of Americans cannot live a Comanche-esque life today. It’s not obvious at all that at least a meaningful minority of Americans wouldn’t be better off living some kind of life like this. Part of the answer may be that it simply does not scale: the Comanches and the Lakotas numbered in the tens of thousands each at their respective peaks — hardly of the scale of modern civilisation in the West. But the answer may be deeper. Perhaps what distinguishes Western civilisation is it’s mythology of progress, coupled with the advent of real technological progress. And what was harsh in 1812 led to luxury in 2022. Maybe we’re mistaken to compare moments in time but must compare trajectories.

Or maybe that is just a story we tell ourselves as we plod on, harnessed to the yoke of civilisation.

Even with the caveats extended — that life was tough for women given the manual labour load and warfare was maximum hellish — it is possible we’re over-romanticising the native American lifestyle in these stories. There are many examples of colonisers going native even after brutal capture, and it’s hard to escape a kind of selection effect where the most colourful and dramatic examples bubble up through history. For example, take this from The Anarchy: The India Company by William Dalrymple:

Of the 7,000 prisoners Tipu captured in the course of the next few months of warfare against the Company, around 300 were forcibly circumcised, forcibly converted to Islam and given Muslim names and clothes. By the end of the year, one in five of all the British soldiers in India were held prisoner by Tipu in his sophisticated fortress of Seringapatam. Even more humiliatingly, several British regimental drummer boys were made to wear dresses – ghagra cholis – and entertain the court in the manner of nautch (dancing) girls.

At the end of ten years’ captivity, one of these prisoners, James Scurry, found that he had forgotten how to sit in a chair or use a knife and fork; his English was ‘broken and confused, having lost all its vernacular idiom’, his skin had darkened to the ‘swarthy complexion of Negroes’ and he found he actively disliked wearing European clothes.

This was the ultimate colonial nightmare, and in its most unpalatable form: the captive preferring the ways of his captors, the coloniser colonised.

If planning to write about how women have it hard, this is a worthwhile read. Woman up!?

https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#inbox/FMfcgzGwJSDbZGVtSrnBXspBQmWxSjPC

Well, there went my morning. I've only read two of these so far and my head is so full I can hardly hold it up. Great stuff, thank you.