WWII Rashomon, Nazi suicides, Great Expectations, Sages on Sex, Tyler Futurism, Public Speaking

"A clear cold Christmas, lovely weather for killing Germans" - General Patton

In this Kvetch:

Who is the enemy? Who is the idiot?

WWII Rashomon

Nazi suicides

Great Expectations

The Sages on Sex

Tyler Futurism vs Effective Altruism

Ted Goia tips for public speaking

Podcast appearance

1. Who is the enemy? Who is the idiot?

Consider this:

Soviet Union: Recieved billions in no-strings-attached US Lend Lease payments, military goods, industrial equipment, intellectual property and food (after fueling the Nazi economy in its war with France and Britain)

Germany: Literally chose Nazism instead of even watered-down WWI reparations, then swiftly subsidised post-war back into the first world by US1

Japan: US subsidised Japan into greater GDP per capita than itself by the 1970s

Britain: Gives up empire, vassal of US, repays US loans with interest in 2006

Who is the enemy? Who is the idiot?

Is Britain the most decent empire in history? Hitler admired her, wanted to ally with her, divide the world in two as the Spanish and the Portuguese had done in 1494, and rule it beside her. Yet Britain said no. Bunkered down. Weathered the Luftwaffe.2 And relinquished its empire to become a US protectorate and supplicant. For what?

Only moral decency.

It’s misleading to talk of “Britain” as a singular actor of course. It was Churchill who stood against Hitler and the loud, almost successful British voices who would have chosen a Hitler alliance. What would you have done?

While Britain immiserated itself, West Germany was subsidised into an economic miracle. While US subsidised West Germany via the Marshall Plan, decorated former Slav-Genocidiers and appointed German Generals to head up NATO, Britain finished repaying its loans in 2006.

US subsidised Japan, the bomber of Pearl Harbour, into greater per capita wealth than the US itself by the 1970s. A strange historic inversion where rather than enslaving a conquered empire and people, the US enriched them.

Eli Weisel noted in his memoir Night how it was impossible to stay in Germany post-war as the citizenry at all levels, complicit in the Nazi regime machinery, determinedly looked forward as the Nazi administrative state was repurposed for Allied use.

And let’s not forget Stalin.

Roosevelt had offered England fifty decrepit World War I–vintage destroyers, in exchange for which Churchill had basically mortgaged the British Empire to Washington. For Stalin, by contrast, Roosevelt had opened a virtually unlimited credit line (initially $1 billion) to order whatever he desired, in exchange for nothing whatsoever. [From Stalin’s War, Sean McMeekin]

By 1941 the Soviet Union allied with the Nazis, invaded, occupied and half-enslaved 7 countries, including massacring 22,000 Polish elites in Katyn forest. (Vasily Blokhin is the most prolific official executioner in recorded world history after killing ~7,000 Poles himself. According to his Wiki: “Blokhin and his team worked without pause for 10 hours each night, with Blokhin executing an average of one prisoner every three minutes.”)

Hitler launched the largest invasion in history. His early gains against the Soviets were astonishing, capturing millions of soldiers and plenty of loot. Stalin is mocked by historians for being caught flat footed. Yet Hitler dramatically underestimated the sheer military vastness of the Soviet Union.3 Quantity has a quality of its own indeed. Hitler considered Stalin mad for purging his officer class in the 1930s. By the end of his life Hitler envied him this. Hitler barely escaped a bomb blast in the plot against him of 20 July 1944 and there were dozens more. He killed ~5,000 “conspirators” in the aftermath of the plot - lagging Stalin’s purges by a decade. Stalin had no known assassination attempts.

Who is the idiot?

In another Kvetch I’ll dive into Hitler’s hubris and the extent of US support for the Soviet Union,4 but according to McMeekin’s Stalin’s War, in 1943, *after* Stalingrad and the turning point of the war, the following % of US production went to the USSR:

12.8% of US pork

12.9% of canned and frozen fish

15.3% of eggs

15.7% of dried fruit

16.8% of beans

By 1943, American wheat made up a third of Soviet consumption and nearly 70% of Russian sugar consumption by 1944.

With enemies like the US, who needs friends?

2. WWII Rashomon

You may have noticed I’ve been going through a bit of a WWII phase. I just read The Wages of Destruction, Hitler and Stalin’s War back to back, so I’ll probably continue to post on WWII. I shared notes for Churchill, The German Generals Talk and Origins of Totalitarianism here and a long thread of my favourite extracts from the excellent Freedom’s Forge here.

This is probably the first time I’ve really read a topic in batch (Tyler Cowen suggests this, and I’ve noted Razib Khan reads like this). The thing is - WWII is so enormous, so fractal, so extreme in every way that it’s impossible to sate. I can understand how a historian might devote their life to a single person or strand of the war. It’s why there are over a thousand Churchill biographies.

Reading dramatically different accounts of history is strange. Partly it’s a question of form: without the ability to literally relive events in some hellish God-like immersive replay, selective retelling through the written word reduces events to an infinitesimally truncated form. Like trying to recreate the ocean with a photo. It says something, but how much?

The sheer scale of the war just means sometimes it’s like the parable of the blind men and the elephant: you’re just touching different parts. But sometimes, it’s like different memories, a kind of Rashomon / The Last Duel effect.

This small example is a perfect illustration of the latter. Kershaw wrote in Hitler:

On the morning of 12 November Molotov and his entourage arrived in Berlin. Weizsäcker thought the shabbily dressed Russians looked like extras in a gangster film. The hammer and sickle on Soviet flags fluttering alongside swastika banners provided an extraordinary spectacle in the Reich’s capital. But the Internationale was not played, apparently to avoid the possibility of Berliners, still familiar with the words, joining in.

McMeekin writes in Stalin’s War:

Just past 11 a.m. on November 12, 1940, Molotov’s entourage arrived at Berlin’s Anhalter Bahnhof. It was a cold, rainy morning, but the Germans had done all they could to provide a proper welcome. An honor guard of the army stood “to immaculate attention,” flanked by Ribbentrop; Hitler’s SS chief, Reichsführer Heinrich Himmler; and the supreme commander of the Wehrmacht, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. The heavy cloud cover accentuated the visual effect as searchlights lit up the Soviet flags hoisted along the platform, carefully blended in with the swastikas. A Nazi band struck up the “Internationale” (played at double time, just in case any nearby Communists might have been tempted to sing), and Ribbentrop gave a welcoming address

Did they play the Internationale at double time or not at all? Maybe we can determine which is right by going to the source material. But this is the smallest possible example. How reliable is the rest?

By the way, I did try and find a photo of that gathering - Nazi and Soviet flags hoisted along together - but failed. Let me know if you know of one.

3. Nazi suicides

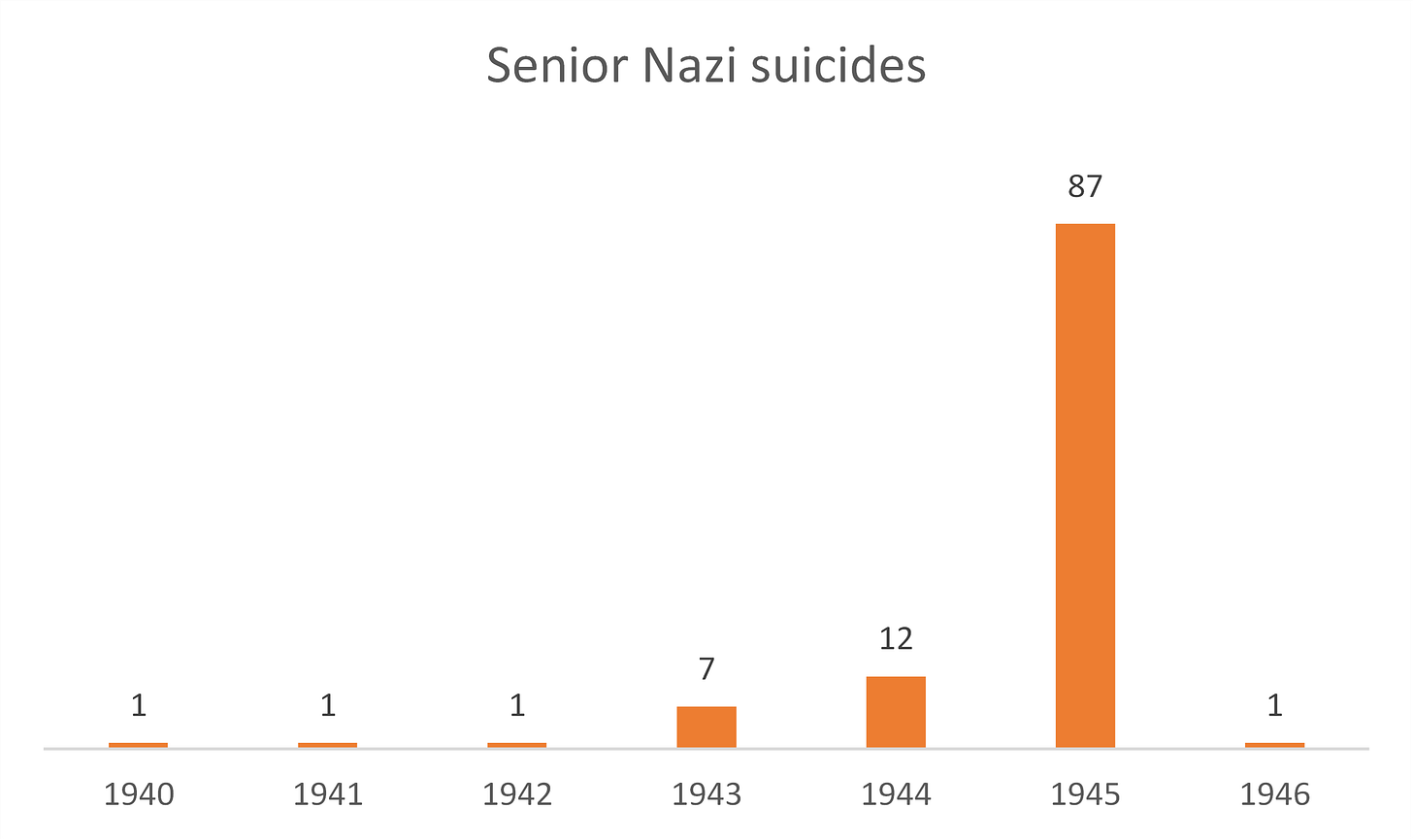

Lots of Nazis ended up killing themselves.

I was curious - and yes, there’s a devoted Wiki page.

As you’d expect, regrettably most Nazis killed themselved towards the end of the war:

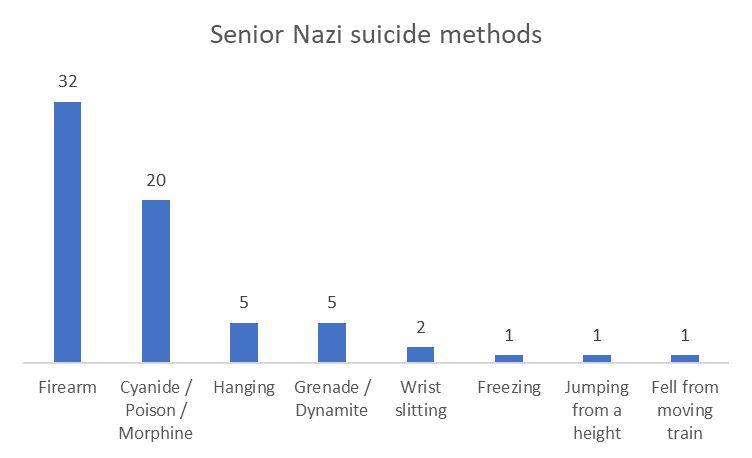

Most preferred to shoot themselves, followed by some method of poison (usually cyanide, which was rather thoughtfully provided by management). Then hanging and blowing oneself up (lower risk of a stuff up I suppose). Only 2 chose the old Roman in a bath tub.

Freezing? Yes, I wondered that also. That’s this chap Otto. Maybe not quite fair to include him with this lot, but he’s on the list. Seems to have been an ecclectic researcher into the Holy Grail - yes like in Indiana Jones. The Nazis were quite into the occult. Anyway, seems he was a rather enthusiastic homosexual, and fell out with the SS. Well it doesn’t work like that and he somehow ended up frozen on a mountain.

One other thing I’ve noticed is that an awful lot of generals seem to die in plane crashes, Allied and Axis. Like this bloke who was promoted to general and killed on his way to take up command. I have not found that list. Stalin was probably right to fear air travel.

General Carl-Heinrich Rudolf Wilhelm von Stülpnagelone did not kill himself, but not for lack of trying. He was a conspirator in the failed 20 July plot to kill Hitler (so close). This was his unfortunate end (from The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich by Willian Shirer):

After a weird all-night champagne party at the Hotel Raphael in Paris in which the released S.S. and S.D. officers, led by General Oberg, fraternized with the Army leaders who had arrested them – and who most certainly would have had them shot had the revolt succeeded – Stuelpnagel, who had been ordered to report to Berlin, left by car for Germany. At Verdun, where he had commanded a battalion in the First World War, he stopped to have a look at the famous battlefield. But also to carry out a personal decision. His driver and a guard heard a revolver shot. They found him floundering in the waters of a canal. A bullet had shot out one eye and so badly damaged the other that it was removed in the military hospital at Verdun, to which he was taken. This did not save Stuelpnagel from a horrible end. Blinded and helpless, he was brought to Berlin on Hitler’s express orders, haled before the People’s Court, where he lay on a cot while Freisler abused him, and strangled to death in Ploetzensee prison on August 30.

4. Great Expectations

My Twitter friend Nemets asked me to post something on Dickens’ Great Expectations.5

There is a passage, near the beginning, that I think of often:

In the little world in which children have their existence whosoever brings them up, there is nothing so finely perceived and so finely felt, as injustice. It may be only small injustice that the child can be exposed to; but the child is small, and its world is small, and its rocking-horse stands as many hands high, according to scale, as a big-boned Irish hunter.

It struck me as exactly right, perfectly describing some inarticulate yet accute sense of injustice I often felt as a young boy, and which I expect many children do (or perhaps it’s just petulance?).

It was this idea I thought of most before I had kids. I wanted to ensure when I became a dad I wouldn’t minimise their grievances. I wouldn’t be dimissive of their concerns - a perceived slight, a missing beloved toy, hurt at parental arbitrariness.

Well, 3 kids and 6 years later, how am I doing?

Mixed I’d say.

We don’t parent in a vacuum. We’re busy. We’re stressed. We can be impatient and short-tempered. And many of a child’s concerns appear invisible to us, existing on a different plane, different spectra of light or sound.

I think the passage is astute, I think of it often, yet it’s not obvious to me that knowing it better attunes my sensitivity. Suspect there’s a sad lesson in that.

Perhaps Nemets would be better off asking Russ Roberts about Great Expectations:

I might ask Russ one day.

5. The Sages on Sex

The Sages knew what every young man eventually discovers: the more sex you have, the more you want it.

Rambam understands the struggle:

6. Tyler Futurism vs Effective Altruism

Tyler Cowen interviews Will MacAskill.

Inject this sentiment into my veins - can I call it Tyler Futurism?

COWEN: Well, take gifts to the opera, which you mentioned. Why should we not build monuments to what has been our greatest and most profound creations, just to show people, “We did this. This is really important. We still think it’s important.” It’s a kind of elitism, but nonetheless, isn’t it important to keep those traditions alive and highly visible?

Based on what I know about EA folk (I’m not anti-EA - one of my best friends is EA!), I’d expect him to be self-aware, but this is surprisingly forthright. Why has EA taken off?

MACASKILL: I think of altruism like a luxury good. The more secure you are, the more you can focus on that…

…the topics are just very intellectually interesting and a very unusual intersection of intellectually interesting and extremely impactful and important for one’s own life, and in fact, how the world should be. You’re making arguments about paradoxes in population ethics and moral philosophy, and the resolution there is really going to make a difference to what you should do. Perhaps that’s more attractive to the nerds of the world, too.

So:

Altruism is a luxury belief

There is a subset of very smart people who care about the world that aren’t into all the tribal progressive stuff that usually sucks in caring young people

Also here is what DALL-E 2 makes of Tyler Futurism:

7. Ted Goia’s tips on public speaking

All very good, I like these two - the deeper take away is that these apply perfectly well to life generally:

(7) Tap into Your Own Craziness:

Every one of us is an odd duck—you, me, and everybody else in the pond. We work hard to hide our peculiarities and nonconforming behavior patterns, especially in front of strangers. I’m now going to tell you to do the opposite. You can learn from jazz musicians in that way—they have fewer inhibitions than most, and will do things on stage the rest of us would never consider. Watch Thelonious Monk get up from the piano to dance. Or Miles Davis turn his back on the audience. Or Sun Ra wearing his Afrofuturist garb as if he just got off the spaceship. Or Dexter Gordon doing that bizarre thing holding his sax sideways like it’s a saint’s relic. The stranger they are, the more we love them. Public speaking is like that too. If you have quirks and eccentricities, let them rip. The audience will remember you for years to come. And, believe it or not, they will remember what you said too.

(10) Be a Rock Star and Savor the Moment:

The audience will feed off your enjoyment. And don’t tell me that it’s impossible to have fun in such a stressful situation. Every last one of us wants to be heard and acknowledged, and you will never find any situation that delivers those goods in more abundance than public speaking. It’s almost as exciting as playing music on stage—in fact, the adrenaline rush feels almost the same in both instances. So just as you are about to begin your talk, tell yourself: I’m a Rock Star and I Totally Rock! And it’s not a lie—for the next few minutes, that will exactly be what you will experience.

8. Podcast appearance

Brief fun chat about valuations, private equity investment processes, and oddities today in VC and credit markets:

“Compared with the Dawes Plan, the [Young Plan] settlement was relatively favourable to Germany. Repayments were to be kept low for three years, and would overall be some 17 per cent less than under the Dawes Plan. But it would take fifty-nine years before the reparations would finally be paid off. The nationalist Right were outraged.” From Ian Kershaw’s Hitler.

As an aside - on British determination - I do love this comment from Maisky, the Soviet ambassador to UK during WWII:

In peacetime the British often look like pampered, gluttonous sybarites, but in times of war and extermity they turn into vicious bulldogs, trapping their prey in a death grip.

Adam Tooze quotes from Halder’s diary in Wages of Destruction:

At the start of the war we reckoned with about 200 enemy divisions. Now we have already counted 360. These divisions are certainly not armed and equipped in our sense, in many cases they have tactically inadequate leadership. But they are there. And when a dozen have been smashed, then the Russian puts up another dozen.

Tooze continues:

In fact, Halder continued to underestimate the scale of the challenge facing the Wehrmacht in Russia. By the end of 1941 the Red Army had fielded not 360 divisions, but a total of 600.

The extent of Soviet infiltration of US industry and politics was staggering.

Context: he posited it’s a shame that high school students are made to read Great Expectations when it’s so dull rather than the bloodier A Tale of Two Cities. I happened to read them in the opposite order - I read Tale when I was in my late teens and don’t really recall it (I read most things the wrong way back then), but read Great Expectations in a glorious year of travel when I was 26 and enjoyed it.

I can’t say I loved it like Moby Dick or The Brothers Karamazov or Blood Meridian or Mrs Dalloway - all of which I read during the same period - but I liked it. (It’s funny how books are placed in time and location of reading, for me anyway).

US didn't subsidize West Germany or Japan into wealth, except in the sense of setting up the conditions for greatly smoothed international trade and security guarantees, which Britain (and most of the world) got as well. Britain got far more Marshall plan aid then Germany did (more then twice as much, despite being a smaller country). The reason Britain got left in the dust postwar was the quasi-socialist command economy they set up after the war, which was only seriously reformed by Thatcher.

I shared notes for Churchill, The German Generals Talk and Origins of Totalitarianism here and a long thread of my favourite extracts from the excellent Freedom’s Forge here.

These links are broken and i would like to read what you wrote