American Will: The Panama Canal

Wresting victory from the earth

The Panama Canal was, at the moment of its completion, the largest structure ever built by man. Its locks — each chamber a thousand feet long, a hundred and ten feet wide, their gates rising eighty feet from the floor, taller than a seven-story building — were formed of more concrete than any construction in human history. To dig the canal, seventy-five thousand men excavated enough earth to build seventy Great Pyramids, enough to bury Manhattan to the depth of a man’s chest.

This the Americans built over ten years and three presidencies.

But before the Americans could build the canal, they had to build the largest artificial lake on earth, flooding an entire river valley to lift ships over mountains. Before they could build the lake, they had to rid the isthmus of pestilence, eradicating yellow fever from a region where it had reigned for three centuries. Before they could eradicate the fever, they had to control the land — which meant staging a revolution, peeling Panama away from Colombia in a single bloodless day.

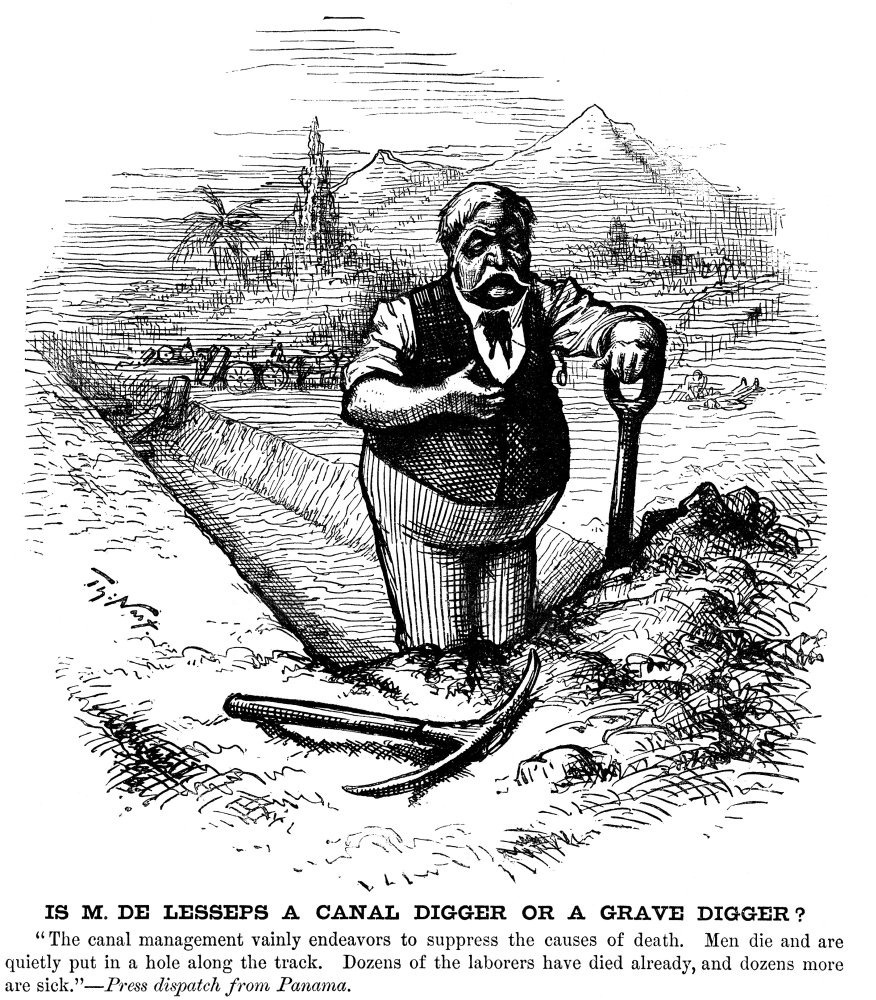

And before any of it — before the lake, before the eradication of fever, before the coup — they had to succeed where the greatest builder of the age had failed. Ferdinand de Lesseps, the hero of Suez, had tried to cut this canal. By 1889 he had spent a decade and $287 million of French savings. He had buried twenty-two thousand men in the jungle earth. And he had accomplished nothing but ruin.

The man who had made the world smaller had sought to cut it in half. Within two years of his triumph at Suez, while Europe still rang with his name, Ferdinand de Lesseps turned his gaze westward — to the dark, fever-haunted jungles of Central America. If he could slice through the sands of Egypt, why not the spine of the New World? In 1879, at the age of seventy-four, he convened an international congress in Paris and, through the sheer gravitational force of his reputation, secured approval for a sea-level canal through the Isthmus of Panama.

The American engineers in attendance — men who had actually surveyed the terrain — knew it was madness. They had spent years tramping through the mosquito clouds and the sucking mud, taking measurements, losing colleagues to fever. They knew the Chagres River, that treacherous serpent that could rise forty feet in a single night of rain. They knew the Culebra Cut, where the mountains slid endlessly, back into any hole you dug. One of them, Adolphe Godin de Lépinay, chief engineer of the French Department of Bridges and Highways, stood before the congress and proposed the only sane solution: dam the Chagres, create a lake, and lift ships over the divide with locks. It was, almost to the metre, the plan the Americans would eventually build. The congress voted him down. De Lesseps wanted a sea-level canal — just as at Suez — and de Lesseps got what he wanted.

What followed was an apocalypse.

The French arrived in 1881 with their mahogany furniture and their Parisian confidence. They found a green hell. The jungle grew so fast that a path cleared at dawn would be impassable by dusk. The rains fell in walls of water, turning excavation sites into lakes overnight. The Chagres, unbound by any dam, regularly flooded the workings. And above all, silent and invisible, came the mosquitoes.

They did not know that the Aedes aegypti carried yellow fever in its bite, or that the Anopheles hummed with malaria. The French doctors, trained in the miasma theory, believed disease rose from freshly turned earth, from noxious jungle vapours. To beautify their hospital at Ancón, they set potted plants around the wards, each pot resting in a saucer of water to keep the ants away. They had built, with loving care, breeding factories for the very creatures that were killing them. Three out of four men who entered that hospital never left.

The workers — mainly black men drawn mostly from Jamaica, Martinique, and Barbados by wages that dwarfed anything the Caribbean could offer — died in their thousands. In the wet seasons of 1882 and 1883, thirty to forty men perished every day. A train ran each evening from the work camps to the cemetery at Mount Hope, its cars brimming with coffins, so many that the living came to call it the funeral express. The dead were often buried in the clothes they wore, stacked in mass graves, their names lost to the jungle. By the time the French abandoned the isthmus in 1889, twenty-two thousand men had been swallowed by the earth they had tried to move.

And the money vanished with them. De Lesseps had raised over 1.4 billion gold francs from eight hundred thousand investors: shopkeepers, widows, country priests, retired soldiers. It was the greatest financial mobilisation in French history, and it evaporated into the swamps of Panama. The company declared bankruptcy in February 1889, having spent $287 million and excavated barely a third of the required earth. The stock was worthless. The canal was a ditch. The scandal that followed — the Panama Affair — brought down ministers, implicated over a hundred members of the French parliament in bribery, and sent Gustave Eiffel himself to trial. De Lesseps and his son Charles were convicted of fraud. The old man, now eighty-eight, was spared prison. He died in 1894, stripped of his glory, his name synonymous with catastrophe.

What remained in Panama was a landscape of mechanical corpses: dredges rusting in stagnant pools, locomotives sinking into the mud, excavators frozen mid-bite like the fossils of some industrial extinction. The jungle was already reclaiming them, vines threading through boilers, trees splitting the rails. For fifteen years, the wreckage sat in the rain, a monument to hubris.

Then came the Americans.

They arrived with a colder, more Protestant kind of will. Theodore Roosevelt, that grinning engine of national ambition, had decided that the United States needed a canal, and he would not be denied by a Colombian senate that refused to ratify a treaty on American terms. In November 1903, with American warships conveniently stationed off both coasts, a small group of Panamanian businessmen with the tacit approval of Washington staged a revolution. It lasted a day. The Colombian troops who landed at Colón found themselves stranded when the American-controlled railroad declined to provide trains. The USS Nashville discouraged any thoughts of marching. Panama declared independence on November 3rd; the United States recognised the new republic three days later; within a fortnight, a canal treaty was signed granting America sovereign rights over a ten-mile-wide strip in perpetuity.

The Americans knew what the French had learned in blood: that Panama was not Suez. The flat desert of Egypt had required only patience and picks; Panama demanded conquest of a continent. But they also knew what the French had not—that the enemies were not the mountains but the mosquitoes.

In 1904, William Crawford Gorgas stepped off the steamer at Colón. He was a slight, courteous Alabaman, the son of a Confederate general, and he had done something that everyone said was impossible: he had rid Havana of yellow fever. Walter Reed and Carlos Finlay had proved that the Aedes aegypti mosquito was the vector; so Gorgas exterminated it, draining every puddle, oiling every cistern, fumigating every room, screening every window. In eighteen months, yellow fever — the scourge that had killed more American soldiers than Spanish bullets — disappeared from Cuba.

Now he would do the same in Panama, but first he had to fight his own government. The Isthmian Canal Commission’s leadership thought him a crank. Mosquitoes? They demanded that he focus on cleaning the streets, burning rubbish, the old miasma protocols. They cut his budget, mocked his methods, recommended his dismissal to the president. But the president gave the doctor whatever he wanted.

Four thousand sanitation workers descended on the isthmus. They drained swamps and ditches by the hundreds of miles. They oiled every pool of standing water with a thin film of petroleum that suffocated mosquito larvae. They screened every building, quarantined every fever case, fumigated entire cities. The hospitals, once charnel houses, were emptied of their potted plants. The little saucers of water disappeared. By the end of 1905, yellow fever cases had plummeted. By late 1906, the last canal worker to die of yellow fever caught the disease — and after that, nothing. The ancient plague that had beaten the French, that had emptied ships in Caribbean harbours for three centuries, was gone from the Zone. It took eighteen months.

Now the building could begin.

The Americans did not attempt a sea-level canal. They had read de Lépinay’s proposal, studied the French surveys, understood the Chagres. They would dam the river, flood an entire valley to create the largest artificial lake on earth — Gatun Lake, twenty-four miles across, covering villages and forests and the ghosts of French machinery — and lift ships eighty-five feet above sea level through a staircase of locks. They were to rearrange the earth.

The locks were the key. Each chamber stretched a thousand feet long and a hundred and ten feet wide — dimensions that would define the maximum size of oceangoing ships for the next century. The walls rose in concrete cliffs, fifty feet thick at their base, reinforced with enough steel to build a navy. The gates, monstrous double-leafed doors that would hold back an ocean, weighed hundreds of tons apiece, their leaves sixty-five feet wide and up to eighty-two feet high — taller than a six-story building, yet so precisely balanced on their hollow steel frames that a single forty-horsepower motor could swing them open. Nowhere on earth had concrete been poured on such a scale; nothing comparable would be attempted until the Hoover Dam two decades later. The steel for the gates and machinery came from Pittsburgh, where entire foundries were given over to the canal. Pennsylvania became, briefly, an extension of Panama.

And the labour that built it was an empire of its own. At the peak of construction, forty-five thousand men worked the Zone, a polyglot army drawn from forty nations. The spine of the workforce came from the British West Indies: Barbadians, Jamaicans, men from St. Lucia and Grenada who crossed the Caribbean on crowded steamers, riding on deck like cargo, chasing the same dreams the French had peddled a generation before. Roughly fifty thousand West Indians passed through Panama during the American decade, a quarter of Barbados’s entire population.

Nothing could have prepared them for the Cut. The men who arrived from Barbados and Jamaica — many from villages where the loudest sound was the wind in the cane and where a donkey cart was the most complex machine — stepped off the trains into something closer to the underworld than any place on earth. The Culebra Cut was a canyon nine miles long and three hundred feet deep, and it was never quiet. Dynamite charges detonated every few minutes, concussions rolling through a man's chest. A hundred trains a day hauled the shattered earth away. Steam shovels the size of houses groaned and swung their loads, their iron jaws biting five tons at a gulp. The noise was so total that men working side by side communicated by hand signal; a shout couldn't carry three feet. And through it all hung the smoke and the red laterite dust, until the sun was just a pale disc in a brown sky. The men who swung the picks and loaded the cars worked inside this machine twelve hours a day, their bodies vibrating with the noise, building a thing that would outlast them all.

But the Americans wanted more. The West Indians were cheap but, the engineers complained, not always efficient. One engineer described a scene where two West Indians would load a wheelbarrow with debris to load it onto the head of a third West Indian who would carry it away. And so recruiters fanned out across Europe, and found, in the valleys of Galicia and the Basque Country and Asturias, a different kind of labourer. Over eight thousand Spaniards — Gallegos, Basques, Asturians — signed on for Panama, paid twice the wage as the West Indian for three times the output. Such discrepancies also reflected the racially segregated working conditions and racial attitudes of the time.

The Culebra Cut — later renamed for the engineer who broke his health directing it, David Gaillard — was the crucible of the enterprise. For nine miles, the canal had to slice through the mountains that formed the spine of the Americas. The French had lowered the Cut’s floor by perhaps three feet in 1886. The Americans lowered it by twenty feet in a single year, then did it again, and again, blasting and shoveling and hauling until they had moved nearly a hundred million cubic yards of rock and clay and mud. The slides never stopped. The walls of the Cut were not solid rock but a treacherous composite of volcanic clay and shale that, when soaked by the endless rains, turned to something like wet soap and slid into the channel, burying steam shovels, swallowing entire work trains. The engineers widened the cut, gentled the slopes, dug and re-dug the same ground. Men died under those slides, buried before they could run. The work went on.

On August 15, 1914, the SS Ancon made the first official transit from the Atlantic to the Pacific. It slipped through the locks, crossed the lake, threaded the Cut, and emerged into the Pacific — a journey of fifty miles, completed in nine hours and forty minutes. They had cut a month and a half and eight thousand miles from a ship’s journey from New York to San Francisco. The canal had come in under budget, and finished a year ahead of schedule. It was the largest, most expensive engineering project in the history of the world, and it had succeeded.

But the world had other concerns that August. On the very day the Ancon made its crossing, German cavalry was riding through Belgium. The opening of the Panama Canal — the supreme achievement of the Progressive Age, the proof that man could bend continents to his will — passed almost unnoticed. The great powers had other ditches to dig now, other mud to die in. The Western Front would consume the same species of young men who had sweated in the Culebra Cut, but in numbers that dwarfed any canal.

The canal would reshape global trade, redraw the strategic maps, make and unmake fortunes. But the age that built it — that confident, muscular, casually brutal era of great works and great men — was already passing into the smoke of the Somme.

Fantastic.

Interesting read. Thanks. One wonders at the gall of man to conceive such a project, much less build it.