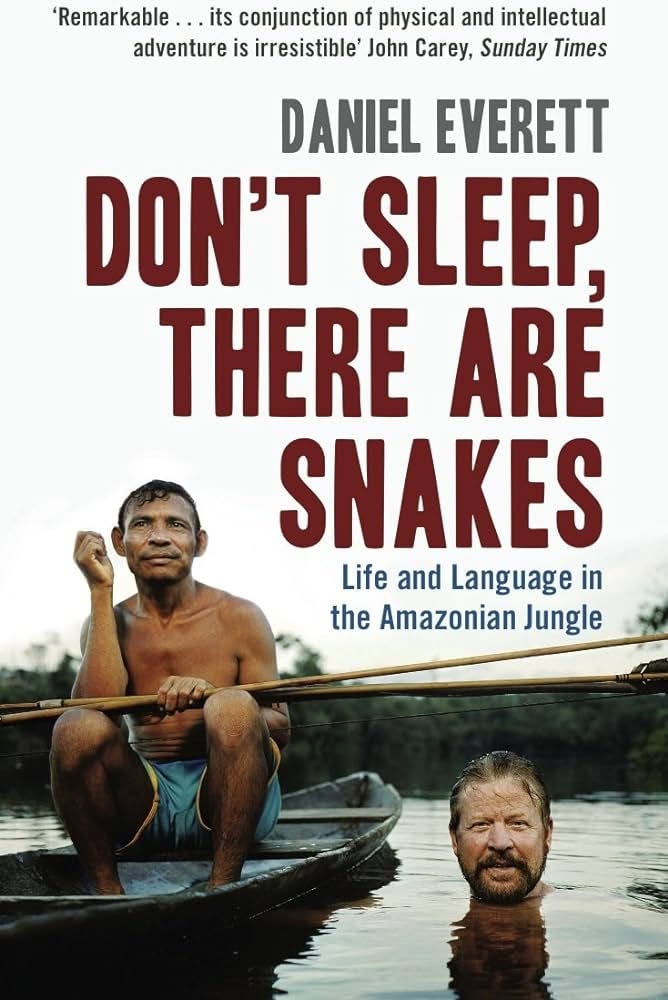

Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes

Men from before the Flood

“She killed herself? Ha ha ha. How stupid. Pirahãs don’t kill themselves,” they answered.

I am haunted by this story from Daniel Everett’s Don't Sleep, There Are Snakes, a love letter to and anthropology of the culture and language of the remote Amazonian Pirahã people:

A young mother named Pokó gave birth to a beautiful baby girl. Pokó and the baby were doing very well. My family and I left the village to rest in Porto Velho, returning two months later. When we arrived back in the village, Pokó and some other Pirahãs, as usual, were living in our house. But Pokó was emaciated. She clearly had some illness, but we didn’t know what. She was close to death, nearly skeletal. Her cheeks were sunken, her legs and arms were bone-thin, and she was so weak that she could barely move. Since she had no milk her baby was also very ill. Other mothers would not nurse Pokó’s baby since they needed the milk, they said, for their own babies. Pokó died just a couple of days after our return. Since we had no radio, we had no way of calling for help for her. But her baby survived.

We asked who would care for Pokó’s daughter.

“The baby will die. There is no mother to nurse her,” we were told.

“Keren and I will take care of the baby,” I volunteered.

“OK,” the Pirahãs responded, “but the baby will die.”

The Pirahãs know death and dying when they see it. I understand this now. But I was committed to helping that baby.

Our first problem was to feed the child. We made some diapers for the baby out of old sheets and towels. We tried to give it a bottle (we always kept baby bottles in the village for possible infant sicknesses), but it would not suck. It was almost comatose. I determined not to let this baby die. I thought of a way to get milk into it. We mixed up some powdered milk with sugar and a bit of salt and warmed it. I had a couple of squeeze bottles of Right Guard deodorant (deodorant is commonly sold in plastic squeeze bottles in Brazil). I emptied them and washed them out. I pulled out the plastic tubes from each and washed those out too. Then I filled a Right Guard bottle with some of our baby “formula.” I connected two of the tubes, wrapping them in medical tape where they were joined. Then I inserted one of them into the Right Guard bottle with the milk. Carefully and slowly we then worked the other tube down the baby’s throat. The baby showed only slight discomfort. With equal care I squeezed slowly on the Right Guard bottle and got quite a bit of milk into the baby’s stomach.

Within an hour the baby seemed more energetic. We fed it every four hours, day and night. For three days we got almost no sleep, working to save this baby. It seemed to be coming around. With each feeding, the baby moved more energetically, cried more loudly, and even had a bowel movement. We were ecstatic. One afternoon we felt we could leave the baby and go jogging on the airstrip. So I asked the father of the baby if he could watch the baby until we got back from the airstrip. We went and jogged, feeling that we were making a tangible and important contribution to at least one Pirahã’s well-being.

…

When we returned from our jog, several Pirahãs were huddled in a corner of our house, and there was a strong smell of alcohol in the air. Those in the huddle looked conspiratorial and stared at us. Some seemed angry, others ashamed. Others just stared down at something on the ground that they were all surrounding. As I approached, they parted. Pokó’s baby was on the ground, dead. They had forced cachaça down its throat and killed it.

“What happened to the baby?” I asked, almost in tears.

“It died. It was in pain. It wanted to die,” they replied.

I just picked up the baby and held it, with tears now beginning to stream down my cheeks.

“Why would they kill a baby?” I asked myself in confusion and grief.

I understand this now.

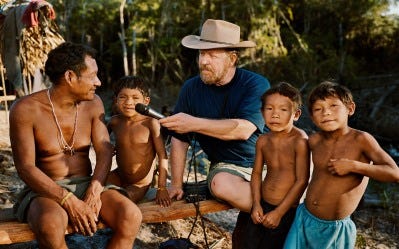

Everett was a protestant missionary. He went out to learn the Pirahã’s language so that he could translate the Bible into it and convert them. He took his young wife and children with him. He gave the Pirahã his youth, spending over thirty years among them. He opens his book with a tribute to the Pirahãs.

The Pirahãs have shown me that there is dignity and deep satisfaction in facing life and death without the comfort of heaven or the fear of hell and in sailing toward the great abyss with a smile. I have learned these things from the Pirahãs, and I will be grateful to them as long as I live.

We should have known at this opening that something was up (a Christian missionary without heaven or hell?). The deeper we go, the deeper the suspicion. The haunting passage I opened with whacks us in the head. Not all is as it seems. Is our narrator unreliable? Has he been compromised? He’s gone native. His mind has been captured by the pagans he went out to convert.

The world of the Pirahãs is fascinating: they are a people eternally in the present. They consider the past only so far as it was witnessed (ideally by one of them).1 So they have no creation myths (if no one was around, how could we know?). They live with scant material objects and amidst the relative plenty of the Amazonian Maici River which bears the fish that sustains them. There is no concept of saving, improvement or progress. They fish with spears — never by rod — and everything from their culture to their language2 prevents them from doing it any other way, no matter how many Americans show them. They do not know numbers, and despite our missionary’s best efforts, cannot learn them.

This is how our man of God explains the Pirahã’s killing of the infant:

The more I thought about this incident, though, the more I came to realize that the Pirahãs, from their perspective, did what they thought was best. They weren’t simply being cruel or thoughtless. Their views of life, death, and illness are radically different from my Western ideas. In a land without doctors, with the knowledge that you have to get tough or die, with much more firsthand direct experience with the dead and dying than I had ever had, the Pirahãs could see death in someone’s eyes and health before I could. They felt certain that this baby was going to die. They felt it was suffering terribly. And they believed that my clever milk tubes contraption was hurting the child and prolonging its suffering. So they euthanized the child. The father himself put the baby to death, by forcing alcohol down its throat. I knew of other babies that had survived their mother’s death, but they had all been in robust health when they were orphaned.

I understand this now.

We don’t actually know why the father and the other Pirahã men killed the baby. This is Everett’s “thought” — his explanation, his rationalisation of their behaviour to himself.

Infanticide was and remains common among primitive peoples, a necessity borne of scarcity. Life for most of time has been harsh. This, for example, is life for Australian Aborigines pre-settlement, where an estimated 20% of newborns were killed (after high rates of natural infant mortality):

To get rid of surplus children, the Iora, like all other Australian tribes, routinely induced abortions by giving the pregnant women herbal medicines or, when these failed, by thumping their bellies. If these measures failed, they killed the unwanted child at birth. Deformed children were smothered or strangled. If a mother died in childbirth, or while nursing a child in arms, the infant would be burned with her after the father crushed its head with a large stone. (Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore)

But here we have a missionary and his wife who pressed against the course of the Pirahã universe. They breathed life into this dying infant, bore responsibility for it. With the miracle of modern medicine, but even more so with their Western eyes. Invested with the hubris of their civilisation, the self-belief that they could manipulate the universe to their wills. And so it was, as they revived the infant and left it to its father for just a moment.

And in that moment the Pirahã returned the universe to its original course: to death. We might witness this moment in the same silent and agnostic horror we watch an alligator eat its young or a stork throw its excess chicks out of its nest. What is one to do, nature, and so on. And yet…. are not the Pirahã invested with agency? Souls, even? Do they not see the baby recover from emaciation? A man before them insisting on life? Why do they insist on death? What is this but evil? And why is our man of God so quick to excuse their evil?

This is not the only time we are jolted from Everett’s Pirahã dream-state.

This paragraph is almost comical in its elided devilry:

Sexual relations are relatively free between unmarried individuals and even between individuals married to other partners during village dancing and singing, usually during full moons. Aggression is observed from time to time, from mild to severe (Keren witnessed a gang rape of a young unmarried girl by most of the village men). But aggression is never condoned and it is very rare.

Look how non-judgmental our missionary is, how he buries the gang rape of a young girl by most of the village men in parentheses. Am I reading Pär Lagerkvis’s The Dwarf? Is this a sick parody? Is this a protestant thing? I feel like an indignant bishop in Rome reading the dispatches of some degenerate padre who’s fathered a tribe of bastards in the New World. Is Everett Colonel Kurtz?3

There’s more:

Steve Sheldon told me about a woman giving birth alone on a beach. Something went wrong. A breech birth. The woman was in agony. “Help me, please! The baby will not come,” she cried out. The Pirahãs sat passively, some looking tense, some talking normally. “I’m dying! This hurts. The baby will not come!” she screamed. No one answered. It was late afternoon. Steve started toward her. “No! She doesn’t want you. She wants her parents,” he was told, the implication clearly being that he was not to go to her. But her parents were not around and no one else was going to her aid. The evening came and her cries came regularly, but ever more weakly. Finally, they stopped. In the morning Steve learned that she and the baby had died on the beach, unassisted.

Everett excuses this kind of thing as Darwinian:

The Pirahãs have an undercurrent of Darwinism running through their parenting philosophy.

Which, again, I find kind of bizarre for a Christian missionary to say? A pro-Darwin, pro-euthanasia Christian missionary? How far do these protestants stray? Or is this all a cry for help — a Christian man expressing a pure Christian love for a misbegotten people buried beneath three decades of total commitment?

Ok, last one:

So long as children are not forced or hurt, there is no prohibition against their participating in sex with adults. I remember once talking to Xisaoxoi, a Pirahã man in his late thirties, when a nine- or ten-year-old girl was standing beside him. As we talked, she rubbed her hands sensually over his chest and back and rubbed his crotch area through his thin, worn nylon shorts. Both were enjoying themselves.

“What’s she doing?” I asked superfluously.

“Oh, she’s just playing. We play together. When she’s big she will be my wife” was his nonchalant reply—and, indeed, after the girl went through puberty, they were married.

I don’t mean to be prudish. I think this example is more interesting for hinting at more — and worse — like it that we suspect Everett does not reveal.

Reading all this, how can one not gasp at the wonder of Western progress? At whatever miracle propelled Europeans to create, to aspire, to conquer the world. In the chasm between these forgotten peoples and our own civilisation, we glimpse an ocean of gratitude. Look at what monogamous marriage has delivered us (harnessing male violence to pro-social civilisation building). The war on disease and death. Ever since Prometheus defied the gods to give man fire, and Jacob wrestled the angel, and Abraham bartered God down to ten righteous men in all of Sodom, and Moses berated God to forgive his people: the Hellenic and Abrahamic traditions, so at odds with each other, but united in their defiance of mere death, of surrender, of savagery.

The Pirahã are an ancient people of the river and the jungle. The gift of Prometheus did not reach them. These are people untouched by the laws of Noah, heirs to the men who provoked God into flooding the earth.

Our missionary narrator does tell another story. The destruction of the Apurinã people who deigned to consider themselves local:

The Apurinã experience illustrates the dark side of Pirahã culture. While the Pirahãs are very tolerant and peaceful to one another, they can be violent in keeping others out of their land. It also shows us once again that tolerance toward a group of outsiders and coexistence with them does not mean long-term acceptance. The Apurinãs had believed that a lifetime among another people could overcome the differences in culture and society that separated them from this other people. They learned the deadly lesson that these barriers are nearly impossible to overcome, in spite of appearances over time—just as residents of the former Yugoslavia, Rwanda, and many other places have learned in the course of history.

This is immediately proceeded by Everett helping the Pirahã to establish their own land:

The solutions that the Pirahãs needed outside help with most were demarcation of their land, to prevent the incursions, and medicines against the diseases.

Everett is quick to point out racism among the various peoples of Brazil or the US. He objects to Brazilian traders calling the Pirahã monkeys and subhuman. He calls them racist. But for the Pirahã, who literally understand the past more or less exclusively through Pirahã eyes and kill non-Pirahãs on their land, racism becomes sparkly demarcation. Ethnocentricity for thee but not for me.

This hypocrisy is familiar. It’s the same condescending tone of ABC journalists calling Australians racist while proposing Aboriginal ethnic enclaves and constitutional committees. It’s unclear which way the causality goes: is Everett a product of popular Western ideology or is Western ideology a product of protestant ideology?

Much of the book is focused on the Pirahã language, which seems to be anomalous.4 Spoken but also whistled,5 yelled, sung, and hummed, it presses the author to adopt some version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, where language and culture and knowledge are intrinsically linked, and studying language as its own separate thing is insufficient. Maybe. Everett is very keen to use the Pirahã as an example to disprove Noam Chomsky’s theory of universal grammar. Curiously, I don’t believe anyone has considered the opposite: rather than considering whether the Pirahã disprove the universality of grammar in humans, maybe their language suggests Pirahã aren’t entirely human? Maybe they’re some ancient cousin. Maybe Everett does consider the Pirahã as we consider the alligator and the stork. Agency for me but not for thee. Seems unlikely — they communicate with Everett well enough — but they do appear to be be culturally and linguistically enmeshed with their slice of the world.

“Pirahãs don’t eat leaves,” he informed me. “This is why you don’t speak our language well. We Pirahãs speak our language well and we don’t eat leaves.”

In the end our missionary did translate the Bible. To tremendous comedic effect. Here is one Pirahã after an evening of listening to recordings and pictures of Mark’s gospel:

As we were working, he startled me by suddenly saying, “The women are afraid of Jesus. We do not want him.”

“Why not?” I asked, wondering what had triggered this declaration.

“Because last night he came to our village and tried to have sex with our women. He chased them around the village, trying to stick his large penis into them.”

Kaaxaóoi proceeded to show me with his two hands held far apart how long Jesus’s penis was—a good three feet.

When Everett tried to convey to them the gravity of his beliefs, how he had come to be saved, the Pirahãs were again immune:

This night, I decided to tell them something very personal about myself—something that I thought would make them understand how important God can be in our lives. So I told the Pirahãs how my stepmother committed suicide and how this led me to Jesus and how my life got better after I stopped drinking and doing drugs and accepted Jesus. I told this as a very serious story.

When I concluded, the Pirahãs burst into laughter. This was un expected, to put it mildly. I was used to reactions like “Praise God!” with my audience genuinely impressed by the great hardships I had been through and how God had pulled me out of them.

“Why are you laughing?” I asked.

“She killed herself? Ha ha ha. How stupid. Pirahãs don’t kill themselves,” they answered.

So — spoiler alert — our missionary apostatised. The immediacy of the Pirahã lives and the irrelevancy of the gospel to them convinced him instead. It broke his marriage. Suddenly, the bubbles of heathen-thought that perplexed us earlier make sense. The man who wrote this book had returned to the Before Times, to the people of the forest and their walking spirits.

Perhaps he could not cease to worry, perhaps he did not find happiness, but he had found a people who could:

I have never heard a Pirahã say that he or she is worried. In fact, so far as I can tell, the Pirahãs have no word for worry in their language. One group of visitors to the Pirahãs, psychologists from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Brain and Cognitive Science Department, commented that the Pirahãs appeared to be the happiest people they had ever seen.

…

My own impression, built up over my entire experience with the Pirahãs, is that my colleague from MIT was correct. The Pirahãs are an unusually happy and contented people. I would go so far as to suggest that the Pirahãs are happier, fitter, and better adjusted to their environment than any Christian or other religious person I have ever known.

It’s really not clear if they consider outsiders sentient:

The Pirahãs would converse with me and then turn to one another, in my presence, to talk about me, as though I was not even there.

“Say, Dan, could you give me some matches?” Xipoógi asked me one day with others present.

“OK, sure.”

“OK, he is giving us two matches. Now I am going to ask for cloth.” Why would they talk about me in front of my face like this, as though I could not understand them? I had just demonstrated that I could understand them by answering the question about the matches. What was I missing?

Their language, in their view, emerges from their lives as Pirahãs and from their relationships to other Pirahãs. If I could utter appropriate responses to their questions, this was no more evidence that I spoke their language than a recorded message is to me evidence that my telephone is a native speaker of English. I was like one of the bright macaws or parrots so abundant along the Maici. My “speaking” was just some cute trick to some of them. It was not really speaking.

Pirahã verbs for fishing mean literally “to spear fish” and “to pull out fish by hand.”

Cormac McCarthy is acknowledged as having read and commented on drafts. How much of the darkness is his hand?

The words for ‘friend’ and ‘enemy’ are almost identical — Rene Girard eat your heart out!

Whistle speech, which the Pirahãs refer to as talking with a “sour mouth” or a “puckered mouth”—the same description they use of the mouth when sucking a lemon—is used only by men. For some reason, this restriction to men is true of most other languages with whistle speech. It is used to communicate while hunting and in aggressive play between boys.

>Curiously, I don’t believe anyone has considered the opposite: rather than considering whether the Pirahã disprove the universality of grammar in humans, maybe their language suggests Pirahã aren’t entirely human?

This was the subtext of the debate between Everett and Chomsky. Chomsky said recursion makes us human. Everett finds people without recursion and then says, "you're not going to say these people are anything less, right?" Even while providing dozens of examples of the Piraha not grokking the human condition. In his next book, Dark Matter of the Mind, he rederives atman---no-self---and says that having a self is culturally constructed. The following year he wrote How Language Began, which argues that language has existed for 2 million years, back with the emergence of our genus. This all follows the assumption that there is not a neurological difference. He spent decades with the Piraha, but never collected any DNA because he didn't want to look racist (his explanation). (Nevermind that if a village in Appalacia displayed half the oddities of the Piraha a genetic test would be the first thing done.) In the end, this didn't work. Based on his description of their lifestyle linguists in Brazil got together to deny his government permit to see them. Ostensibly this was done for the protection of the piraha, but they obviously love him and he has helped them protect their land. But clearly the linguists were protecting their blank slate theories from information that was difficult to explain.

To your point about the Piraha being from before Noah, I suspect that may literally be true. Though I would go back further, to Eden. I think that the Fruit of Knowledge is a metaphor for understanding yourself as a moral agent who will one day die. Culture with that understanding baked in spread worldwide around the end of the Ice Age along with serpent worship and stories of women making the discovery of self-as-agent. There were people in the Americas before that cultural package arrived ~15kya, and maybe the Piraha are the sole holdout. They have no ritual, no religion, and no god. Though Everett makes one exception: they will sometimes dance with venomous snakes.

You may enjoy my grand theory about the role of a primeval snake cult which spread with self-awareness. Maybe the Piraha are drop-outs: https://www.vectorsofmind.com/p/the-snake-cult-of-consciousness

Quote from Don't Sleep in which the snake dance is described:

“Pirahãs have told me about a dance in which live venomous snakes are used, though I have never seen one of these (such dances were corroborated, however, by the eyewitness account of the Apurinã inhabitants of Ponto Sete, before the Pirahãs dispersed them). In this dance, the regular dancing is preceded by the appearance of a man wearing only a headband of buriti palm and a waistband, with streamers, made entirely of narrow, yellow paxiuba palm leaves. The Pirahã man so dressed claims to be Xaítoii, a (usually) evil spirit whose name means “long tooth.” The man comes out of the jungle into the clearing where the others are gathered to dance and tells his audience that he is strong, unafraid of snakes, and then tells them about where he lives in the jungle, and what he has been doing that day. This is all sung. As he sings, he tosses snakes at the feet of the audience, who all scramble away quickly.

These spirits appear in dances in which the man playing the role of the spirit claims to have encountered that spirit and claims to be possessed by that spirit.”

> The Orks are the pinnacle of creation. For them, the great struggle is won. They have evolved a society which knows no stress or angst. Who are we to judge them? We Eldar who have failed, or the Humans, on the road to ruin in their turn? And why? Because we sought answers to questions that an Ork wouldn’t even bother to ask! We see a culture that is strong and despise it as crude.