Tasmanian Aborigines

The destruction of one people by another

And strangest of all there existed, shadowy among the ferns and gum-trees, a race of human beings altogether unique, different ethnically and culturally from the aboriginals of the Australian mainland, and living, in their secluded forest encampments, or crouched over wood-fires on shellfish shores, lives unaffected by contact with any other men and women than themselves. From the moment these people first set eyes upon an Englishman, they were doomed.

— Jan Morris, Heaven’s Command

In Niall Ferguson’s Empire, the destruction of the Aborigines of Van Diemen’s Land represents a unique blemish on the record of the British Empire.

In one of the most shocking of all the chapters in the history of the British Empire, the Aborigines in Van Diemen’s Land were hunted down, confined and ultimately exterminated: an event which truly merits the now overused term ‘genocide’.

Exactly this concern for British repute in posterity animated the government in London even at the time:

Reading [Lieutenant Governor] Arthur’s reports in London, Sir George Murray, secretary of state for the colonies, had felt a tingle of premonition: “The whole race of [Van Diemen’s Land Aborigines] may, at no distant period, become extinct. . . . [A]ny line of conduct, having for its avowed, or for its secret object, the extinction of the Native race, could not fail to leave an indelible stain upon the character of the British Government.” (Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore)

So what exactly happened in Van Diemen’s Land?1

No one knows quite how many Aborigines lived on this island when Dutch explorer Abel Tasman discovered it in 1642, but estimates range up to 4,000. They built no homes or structures. The only trace they left dissolved along their hunting routes. So atavistic a race of man were they that it’s been contended that they lost knowledge of fire:

When finally encountered by Europeans in A.D. 1642, the Tasmanians had the simplest material culture of any people in the modern world. Like mainland Aborigines, they were hunter-gatherers without metal tools. But they also lacked many technologies and artifacts widespread on the mainland, including barbed spears, bone tools of any type, boomerangs, ground or polished stone tools, hafted stone tools, hooks, nets, pronged spears, traps, and the practices of catching and eating fish, sewing, and starting a fire. (Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel)

They probably didn’t lose knowledge of fire, but that does not detract from their ancient and lonely isolation.

The most isolated people on Earth in recent history were the Aboriginal Tasmanians, living without oceangoing watercraft on an island 100 miles from Australia, itself the most isolated continent. The Tasmanians had no contact with other societies for 10,000 years and acquired no new technology other than what they invented themselves. (Jared Diamond, Guns, Germs, and Steel)

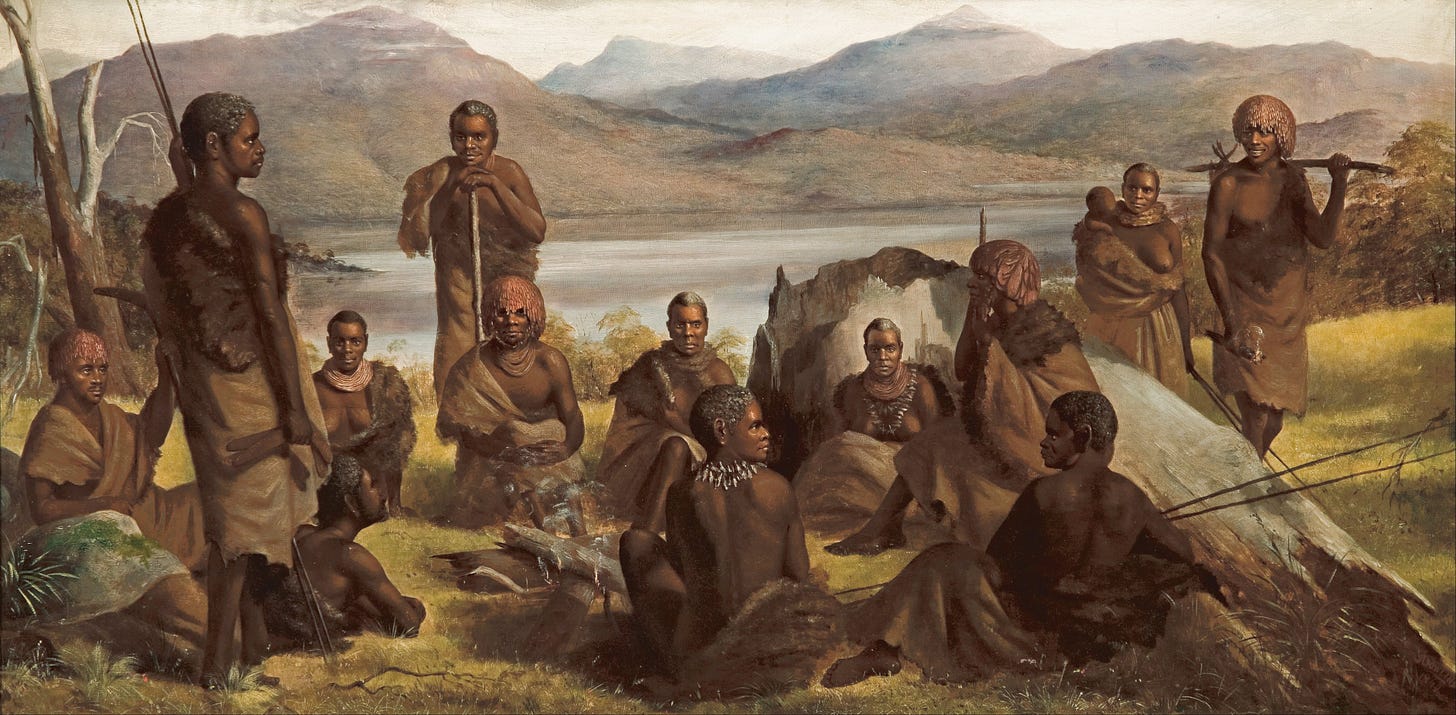

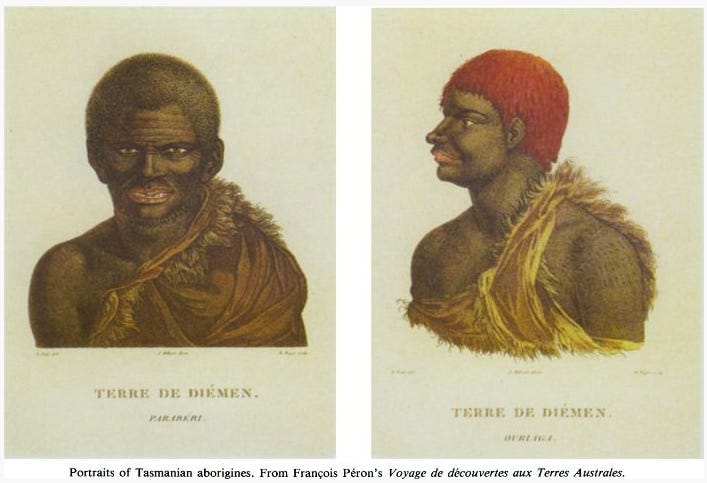

The people of this island were distinct to those of the mainland. This is how Jan Morris colourfully described them, which you might forgive some creative license:

They were smallish but long-legged people, red-brown rather than black, with beetle-brows, wide mouths, broad noses, and very deep-set brown eyes. The men had rich beards and whiskers, and the women were hirsute too, often developing incipient moustaches…. To modern tastes, if we are to judge by surviving photographs, they might not seem so disagreeable: they look homely, but oddly wistful, like elves, or perhaps hobbits—there is something very endearing to their squashed-up crinkled faces...

The Tasmanians did not by and large wear any clothes, except for loose cloaks of kangaroo skin, but they smeared their bodies with red ochre, and wore necklaces of shells or human bones. They slept in caves or hollow trees, or beneath rough windbreaks of sticks and fronds, and their staple foods were kangaroos and wallabies, supplemented by shellfish, roots and berries, fungi, lizards, snakes, penguins, herons, parrots and the eggs of ants and emus. Physically they seem to have lacked stamina: their senses were uncannily acute, and they were adept at running on all fours, but they were not very strong, nor very fast, nor even particularly agile. They made crude boats of bark or log, but never ventured far out to sea: instead they roamed incessantly, pursuing the fugitive marsupials, through the dense bush forests of their island, over its wide downlands, or down to the shingle shore to eat oysters.

This Tasmanian hairstyle reminds me of the Namibian Himba women, whom I saw up close a few years ago (not my photo):2

Europeans saw no threat in the island’s people.

In 1777 Captain Cook found the natives trustful and unafraid, while the Frenchmen of Nicholas Baudin’s expedition, in 1802, seem to have been enchanted by them. ‘The gentle confidence of the people in us, the affectionate evidences of benevolence which they never ceased to manifest towards us, the sincerity of their demonstrations, the frankness of their manners, the touching ingenuousness of their caresses, all concurred to excite within us sentiments of the tenderest interest’. (Jan Morris, Heaven’s Command)

But Tasmanians had much to fear.

It is underappreciated how few these people were. Just as the great Plains Horse empires of the Comanche and Lakotas loom far larger in American history than their mere tens of thousands suggest, so does the black stain of Tasmanian genocide seem to imply more than a population of a few thousand. Of course, as the Jewish sages said, whoever destroys a life is considered to have destroyed an entire world. But the reality is they were largely extinguished before anyone had realised. How many peoples of a few thousand across time have disappeared without a trace, murdered or driven out by fiercer nomads or expanding settlements, unrecorded by modernity and lost to posterity? Known are the Moriori, perhaps 2,000 massacred and enslaved by the Maori. How many native American peoples fell to the Plains Horsemen in their ascendency? How many peoples lost in the rise and fall of Hindu kingdoms over millennia? Annihilated by the millions-strong Incan or Aztec empires discovered by Pizarro and Cortes? Crushed between waxing and waning empires across Europe and the near east? The communities on other remote Australian islands (Flinders, Kangaroo, King), appear to have numbered in the hundreds and simply died out.

The Tasmanian natives died in the same way countless others died across history as stronger peoples encroached on weaker. It was not the intention or policy of the governments of the day to kill the Tasmanians — neither in London nor locally. That does not make their end any less brutal. The wanton murder, enslavement, and rape of Tasmanian natives by sealers, whalers, convicts, bushrangers, and settlers in the first decades of the 1800s reads like a horror story from a Cormac McCarthy hellscape. Here Robert Hughes describes the life of “a bright, promiscuous girl named Trucanini”, the last Tasmanian Aboriginal:

She was very small, only 4 feet 3 inches high, and had pronounced curly whiskers; in other respects, all white witnesses agreed, she was remarkably attractive—for an Aborigine. As a child, she had seen her mother stabbed to death in a night raid by whites; later, a sealer named John Baker had kidnapped two of her tribal sisters and her blood sister, Moorina, and taken them in slavery to the tribe of white pirates that lived on Kangaroo Island, far to the west off the coast of South Australia. Her stepmother was abducted by the convict mutineers of the brig Cyprus and must have died as they were seeking China; she was never heard from again. Around 1828, she was crossing from the mainland to Bruny Island with several tribesmen, to one of whom she was “betrothed,” in a boat manned by two convict loggers. In mid-channel, the whites seized the black men and threw them overboard; when they grabbed for the gunwale and tried to haul themselves up, the loggers chopped their hands off and left them to sink. They then rowed her ashore and raped her. Trucanini, one would presume, had every reason to hate the whites. In fact she sought their company thereafter and was busy becoming a sealers’ moll, sterile from gonorrhea, hanging around the camps and selling herself for a handful of tea and sugar…

In addition to the horrors of the seafarers was the sadism of bushrangers:

Perhaps ten blacks were killed for every white, perhaps twenty. At first the dirty little war sputtered its way around Hobart and the banks of the Derwent, as settlers in the starvation years competed against blacks for the kangaroos. Sometimes whites killed blacks for sport. In 1806 two early bushrangers, John Brown and Richard Lemon, “used to stick them, and fire at them as marks whilst alive.” Another escaped convict, James Carrott or Carrett, abducted an Aborigine’s wife near Oyster Bay, killed her husband when he came after them, cut off his head and forced her to wear it slung around her neck in a bag “as a plaything.” There were rumors that kangaroo-hunters would shoot blacks to feed their dogs. Two whites cut the cheek off an aboriginal boy and forced him to chew and swallow it. At Oatlands, north of Hobart, convict stock-keepers kept aboriginal women as sexual slaves, secured by bullock-chains to their huts. On the Bass Strait coast, marauding sealers would try to buy women from the tribes; the usual offer was four or five sealskins for a woman, but if the Aborigines would not sell, they would shoot the men and kidnap the women. When one of these women tried to run away from the sealers, they trussed her up, cut off her ears and some flesh from her thigh and made her eat it.

Despite the protestations of the lieutenant-governors of the period, who insisted that the natives had every protection under English law, the persecution continued.

And if the sea-hunters and the bushrangers weren’t enough, there were the recriminations of the settlers. In 1827 there were 436,256 sheep in Van Diemen’s Land. By 1836 there were 911,357 — 20 sheep for every white person in the colony. As the blacks were brutalised and their land taken by whites and encroached upon by sheep, they fought back. They fought as they could, burning thatched rooves and luring stockmen into the bush where they could be more easily killed and then melting away. This worked the white settlers into a frenzy, who called for their extermination, imagining a dark menace preparing to emerge from the woods to kill them.

Governor Arthur knew who to blame:

“All aggression originated with the white inhabitants, and . . . much ought to be endured in return before the blacks are treated as an open and accredited enemy by the government.” (Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore)

Meanwhile:

the whites kept slaughtering the blacks, women and children usually first, with musket and fowling piece, cutlass and ax. By 1830, there were perhaps two thousand Aborigines left alive in Van Diemen’s Land. (Robert Hughes, The Fatal Shore)

The Black Line

Arthur came up with a scheme to move the natives to the north-east coast of Van Diemen’s Land where they could be cared for and protected from the white settlers.

It took the form of an immense pheasant-drive… Some 2,200 men formed the Black Line—550 troops from the 17th, 57th and 63rd Regiments, 700 convicts, and the rest free settlers. They carried between them a thousand muskets, 30,000 rounds of ammunition and 300 pairs of handcuffs with which to subdue the resistant natives…

It took the Black Line seven weeks to converge, like the closing of a fishing net, on the peninsula. A few Aborigines were spotted, and there were some brief skirmishes; two Oyster Bay tribesmen were captured and two others shot, but Arthur was certain that the main mass of them were fleeing ahead of the Black Line toward the Tasman Peninsula…

When the net closed, it was empty. The Black Line had caught two Aborigines, a man and a small boy. All the rest had slipped through. The enterprise had been a fiasco…

So the Tasmanian’s great drive came to naught, for there was barely anyone left to catch, and few enough to slip through. Unbeknownst to the government, by that time the whalers and sealers and bushrangers and settlers had already decimated the small, fragile population.

Confinement and death

Following the failure of the Black Line, one George Augustus Robinson proposed something new: he would engage with the remaining tribes and bring them out of the wilderness to make civilised Christians of them. And so he embarked on an 8 month journey with a party that included Trucanini, “the archtraitor to her race” (per Hughes).

Here I leave you with Hughes in The Fatal Shore, who inimitably draws out the sad end of the Tasmanian Aborigines.

Slowly, the blacks followed him; and when he brought in the last of the once-feared warriors of the Big River and Oyster Bay tribes—a pathetic group of sixteen people—he was greeted like a Roman conqueror in Hobart…

Thus, by 1834, the last Aborigines of Van Diemen’s Land had followed their evangelical Pied Piper into a benign concentration camp, set up on Flinders Island in Bass Strait. There, Robinson planned to Europeanize them. They were given clothes, new names, Bibles and elementary schooling. They were shown how to buy and sell things, so that they might acquire a reverence for property. They were allowed to elect their own police. In the main, however, they simply died—of accidie, deracination and new diseases. In 1835, only 150 Aborigines were left. Little by little, they wasted away and their ghosts drifted out over the water. Robinson left Flinders in 1839 and returned to the Australian mainland. His successors chose to treat Flinders Island as a jail, and its dwindling colony of Aborigines as prisoners. Occasionally a girl would be flogged, but only for moral offenses. In 1843 there were fifty-four Aborigines alive… In 1855 the census of natives was three men, two boys and eleven women, one of whom was Trucanini.

The last man died in 1869. His name was William Lanne and he was described as Trucanini’s “husband,” although he was twenty-three years her junior. Realizing that his remains might have some value as a scientific specimen, rival agents of the Royal College of Surgeons in London and the Royal Society in Tasmania fought over his bones. A Dr. William Crowther, representing the Royal College of Surgeons, sneaked into the morgue, beheaded Lanne’s corpse, skinned the head, removed the skull and slipped another skull from a white cadaver into the black skin. This gruesome ruse was soon unmasked, for when a medical officer picked the head up, “the face turned round and at the back of the head the bones were sticking out.” In pique, the officials decided not to let the Royal College of Surgeons get the whole skeleton; so they chopped off the feet and hands from Lanne’s corpse and threw them away. The lopped, dishonored cadaver of the last tribesman was then officially buried, unofficially exhumed the next night and dissected for its skeleton by representatives of the Royal Society. It was, one of them remarked with some understatement, a “dirty job.” Lanne’s skeleton then disappeared; and the head, which Crowther consigned by sea to the Royal College of Surgeons, vanished too. It seems that the ineffable doctor had packaged it in a sealskin, and before long the bundle stank so badly that it was tossed overboard.

Trucanini wept and raged inconsolably when she was told of the fate of Lanne’s body. She had long been frightened of death and of the evil spirit Rowra who would exact the revenge of the dead tribes she had betrayed; but now a further terror joined those. She begged a clergyman to make sure that when she died, she would be wrapped in a bag with a stone at her feet and dropped into the deepest part of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel—“because I know that when I die, the Tasmanian Museum wants my body.” By 1873, the last of her black companions was dead and Trucanini was taken to Hobart, where she lingered on in a wretched aura of colonial celebrity, invented by the whites, as the “Queen of the Aborigines.” One May evening in 1876 she was heard to scream, “Missus, Rowra catch me, Rowra catch me!” A stroke felled her, and she lay in coma for five days. Her last words, as the dark peeled back for a moment from her terrified consciousness, were, “Don’t let them cut me, but bury me behind the mountains.”

The government arranged a funeral procession for the last Tasmanian on May 11, 1876. Huge crowds lined the pavements to watch her small, almost square coffin roll by; they followed it to the cemetery, and saw it lowered into a grave. It was empty. Fearing some unseemly public disturbance, the government had buried her corpse in a vault of the Protestant Chapel in the Hobart Penitentiary the night before. So Trucanini lay not “behind the mountains,” but in jail. In 1878 they dug her up again and sloughed the flesh off her bones, then boiled them and nailed them in an apple crate, which lay in storage for some years. The crate was about to be thrown out when someone from the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery read the faded label. The bones were strung together, and the skeleton of Trucanini went into a glass case in the museum, where it remained until feelings of public delicacy and humanitarian sentiment caused it to be removed, in 1947, to the basement. In 1976, the centenary of her death, the authorities—not knowing what else to do with this otherwise ineradicable dweller in their closet—had it cremated, and the ashes were scattered on the waters of the D’Entrecasteaux Channel.

Van Diemen’s Land was renamed Tasmania in 1856 to distance the island from its dark penal past.

Did Jared Diamond link Tasmania and Namibia for this reason or is that a coincidence? From Guns, Germs and Steel:

Technological advances seem to come disproportionately from a few very rare geniuses, such as Johannes Gutenberg, James Watt, Thomas Edison, and the Wright brothers. They were Europeans, or descendants of European emigrants to America. So were Archimedes and other rare geniuses of ancient times. Could such geniuses have equally well been born in Tasmania or Namibia?

Hmmm, we really haven’t learnt much, have we? Interesting article, a bit depressing, but I’ll take that over ignorance. Thanks for writing.

Harrowing stuff, thanks for writing.