The Woman's Burden

The feminists are right

Woman does not dream of transcendental or historical escape from natural cycle, since she is that cycle. Her sexual maturity means marriage to the moon, waxing and waning in lunar phases. Moon, month, menses: same word, same world. The ancients knew that woman is bound to nature’s calendar, an appointment she cannot refuse. The Greek pattern of free will to hybris to tragedy is a male drama, since woman has never been deluded (until recently) by the mirage of free will. She knows there is no free will, since she is not free. She has no choice but acceptance. Whether she desires motherhood or not, nature yokes her into the brute inflexible rhythm of procreative law."

— Camille Paglia, Sexual Personae

Some of the early signs of pregnancy are nausea and soreness in the breasts. Nausea usually persists through the first trimester, although in rare cases an extreme form (which carries the Harry Potter enchantment name Hyperemesis Gravidarum) may induce severe vomiting and render the woman bedridden for the entire term. Over the pregnancy the woman grows a child of 3 - 4 kilograms inside her, but a child is a minority part of her weight gain. She grows an entire new organ — the placenta — to sustain the baby, as well as generates amniotic fluid, increased blood and fluid volume, larger breasts, and increased fat stores. As the baby and placenta grow in tandem, they press her internal organs out. This ranges from somewhat uncomfortable to constant pain. Hormonal fluctuations can trigger emotional upheavals.

Birth is its own physical trauma. A woman’s cervix must dilate from 0 centimeters to 10 centimeters for childbirth to occur. Nurses and doctors will check dilation and the baby’s state, which means people’s fingers going in all sorts of places. (Rachel, played by deranged-protagonist-extraordinaire Claire Danes, in Fleishman is in Trouble is traumatised by one such violation. “It was the worst day of her life”, said the narrator, catalysing a spiral into depression.) A baby the size of a small watermelon will pass through the dilated cervix. The mother would like to avoid tearing if possible, especially a perineal tear, which is where the tear reaches the anus. Surgical repair may be required. It’s all about as violent as you’d expect, and about as violent an episode as you’re likely to witness in our sanitised modernity. And that’s all if things go well. She may require a caesarean — where the mother’s abdomen and uterus is cut open to deliver the baby.1 There are many reasons this may be required, but needless to say in the not-so-distant past they may well have led to the death of the infant if not the mother.

After childbirth, outside the normal pangs of recovery, a mother may experience incontinence or prolapse. Prolapse is when the muscles and tissues supporting the pelvic organs (the uterus, bladder, or rectum) become weak or loose. Up to half of mothers experience some form of prolapse. These muscles and tissues may tear during childbirth and require surgery, or the mother will bear a distended abdomen thereafter if she goes without. During pregnancy, a woman’s estrogen, progesterone, and oxytocin levels are high. These hormones drop sharply post-partum, effecting mood swings and sometimes triggering depressions. Other permanent changes might occur. My wife, for example, permanently lost her taste for coffee, eggs and chili.

This is all to say pregnancy is hard. At best the mother is vulnerable and needy and at worst she suffers for the full 9 months plus whatever afflictions she incurs through childbirth and recovery. Online mothers’ groups are dens of horror stories. It’s no wonder that all the above is more or less hidden from young women (and obviously totally invisible to oblivious young men). Yes, she knows that pregnancy exists, but social rituals and the romantic story of one’s life hide or elide the burdens of pregnancy and childbirth, and human memory plays tricks, memory-holing the worst of it for the sake of multiple children and the future of humanity. Having multiple children is an exercise in fooling yourself regarding past experiences and committing your future self to pain.2 No wonder mothers have so many ways to infuse the process with meaning to distract themselves from the ordeal.

Pregnancy is not just one part of womanhood. A woman’s body is built around this process. Humanity depends on it. It’s probably too presumptuous to call it the apotheosis of womanhood, but it sure takes up a lot of time and energy, and is a clear demarcation from one stage of life to another. 3 kids means over two years being pregnant.

What is man’s equivalent? What violent duty does he assume for the family? Protecting and hunting and war carry the real risk of death or trauma. Or it did. Maybe it still applies to some occupations and to some places, but not to us. Not in sunny Sydney. Certainly not to the laptop class probably reading this. And so as men’s assumption of risk has diminished, is it any surprise that woman too are reducing their appetite for the violence of pregnancy and childbirth?

A woman transitions from youthful splendour and the object of suitors to the drudgery of motherhood. Women can of course become even more attractive with motherhood. (Only good taste prevents me from showering you with proof of how even more stunning my own wife became after our firstborn.) But motherhood — the transition from youthful exuberance to the project of family building — is hard, and this period is marked by the normal anxieties of aging and metamorphosis.

Pregnancy is not the only affliction of womanhood. As a man, one never quite wraps one’s mind around menstruation. Biblically and culturally around the world, it is a potent and mystical event. I defer to an actual woman on the subject, and none other than Germain Greer in The Female Eunuch:

Why should women not resent an inconvenience which causes tension before, after and during; unpleasantness, odour, staining; which takes up anything from a seventh to a fifth of her adult life until the menopause; which makes her fertile thirteen times a year when she only expects to bear twice in a lifetime; when the cessation of menstruation may mean several years of endocrine derangement and the gradual atrophy of her sexual organs?3

(I thought it was more than “a seventh to a fifth” but whatever.)

I write all this as a sort of corrective. From the Domestication of Man4 series to Suffering Wives to Sex and Agency to Feminisation and others, readers might get the wrong impression that my writing is anti-feminist. My sister says she enjoys my posts but often finishes them annoyed. My wife also glares at me on occasion. I don’t think this is a correct reading of my essays. So I would like to issue this corrective!

And so I say: the feminists are right! Germain Greer, Clementine Ford, RFH, take your pick. Sure on any number of particulars I might disagree — Greer goes horrendously off course in The Female Eunuch and Ford can be a little harsh (“coronavirus isn’t killing men fast enough”), but I think the case that women bear the brunt of life’s burdens and men are basically degenerates is true enough. (But what does that say about anyone who is foolish enough to be attracted to men? You see, there I go being annoying again.)

In one sense, this is self-evident. Violence is almost exclusively the purview of men, as is sexual assault. Man is a creature of ego. If you assume all he does is to satisfy his ego, you’ll be more right than wrong.

The happiness of man is, “I will”; The happiness of woman is, “He will.”

— Thus Spake Zarathustra

Men will find the most beautiful, accomplished woman they can and rip her from her work to bear his children. A woman’s desires in marriage are simple and fair enough: a loving husband who attends to her and provides for the family. Given the vulnerably she endures in pregnancy, this is as understandable as it is necessary. She ‘domesticates’ him to that end, if she is successful. The implication that he is some wild beast is more flattering than the reality: he is a slob or a brute. More often than not in her husband she must suffer some degree of vice. Maybe he’s a pothead or spends countless hours gaming or watching porn (Twitter isn’t a vice, right? Right??). Maybe he likes to drink or to bet on the dogs. He might beat her. Perhaps his vice is women or men or total inattention. One never truly knows the contents of another’s marriage, but even given that I’ve known of strange husband demands. In one case he demands that she dress up more for dinner and that dinner be more elaborate. Another husband controls the finances and releases trivial funds subject to certain sexual demands being met. No doubt such sins are multitude.

Women are not free of vice, and they have their derangements and means of driving their husbands mad. But man is born to vice; woman merely adopts it.

It’s no surprise that when you give women choice, when you given them cultural, legal, political and financial freedom — they choose to bear fewer children and what children they bear they bear later. After they have accrued enough financial and social capital to avoid total dependence on a man.

Women have proven at least as capable as men in a swathe of lucrative and high caliber roles. When I was at law school in the late 2000s, someone joked that the last male solicitor had already been born. Women will pursue any number of careers but then face an impossible choice. When I was 21, I met a 26 year old doctor in the early stages of her career. She wanted to become an orthopedic surgeon. But she was far-sighted enough to know that the decade of work ahead of her to become one coincided with her peak fertility years. And that caused her a great deal of angst: would she rather renege on her professional ambition or her desire to have a family? Her story gave me a glimpse into another world. Existential dilemmas for her but not for me.

15 years on we can see the results for my generation. Smart, beautiful women in their late 30s or early 40s stuck in soulless careers and abandoning hope for children, or suffering the grueling, expensive and low probability trials of IVF. Regrets, they have a few.

For some, choosing motherhood is a genuine culmination of a dream and is satisfying enough. For others, giving up a career, or taking a long break, is socially isolating and intellectually unfulfilling. Motherhood can be dreary, lonely and monotonous. Even if she genuinely loves her kids and would make the same choice again, it’s a harsh trade.

Men don’t face the same tradeoff. Fatherhood is hard for many reasons. But much of the logistical overhead of childrearing and housekeeping is left to her. That’s even outside of the years of pregnancy and childbirths. His end of the bargain — providing — also happens to coincide often enough with his intellectual and social interests (or at least, again, amongst this readership).

If life was hard for all in the past, it was especially hard for women. Will Durant writes in Story of Civilization I: Our Oriental Heritage:

All in all the position of woman in early societies was one of subjection verging upon slavery. Her periodic disability, her unfamiliarity with weapons, the biological absorption of her strength in carrying, nursing and rearing children, handicapped her in the war of the sexes, and doomed her to a subordinate status in all but the very lowest and the very highest societies.

He continues:

Bushwomen were used as servants and beasts of burden; if they proved too weak to keep up with the march, they were abandoned. When the natives of the Lower Murray saw pack oxen they thought that these were the wives of the whites.

"Women," said a chieftain of the Chippewas, "are created for work. One of them can draw or carry as much as two men. They also pitch our tents, make our clothes, mend them, and keep us warm at night. We absolutely cannot get along without them on a journey. They do everything and cost only a little; for since they must be forever cooking, they can be satisfied in lean times by licking their fingers."

Nor do we need to go back to primitive societies. Look only at the grueling description of women’s work in the coal mines of 19th century Britain or the withering effects of virtual medieval serfdom in Texas’s Hill Country in the 20th century.

“If men loved Texas, women, even the Anglo pioneer women, hated it. In diaries and letters a thousand separate farm wives left a record of fear that this country would drive them mad.”

— T.R Fehrenbach

If men are domesticated, and women do the domesticating, it is because women are already bound. By the necessities of creation and the life-giving mechanisms with which they are endowed, as well as the brutish world they inhabit, women are not born free.

Modernity has done much to alleviate the burdens of womanhood, and relatively speaking, women have never had it better. Technology has been the great emancipator of women, as of men. But zooming in on the 20th century, the story is more nuanced.

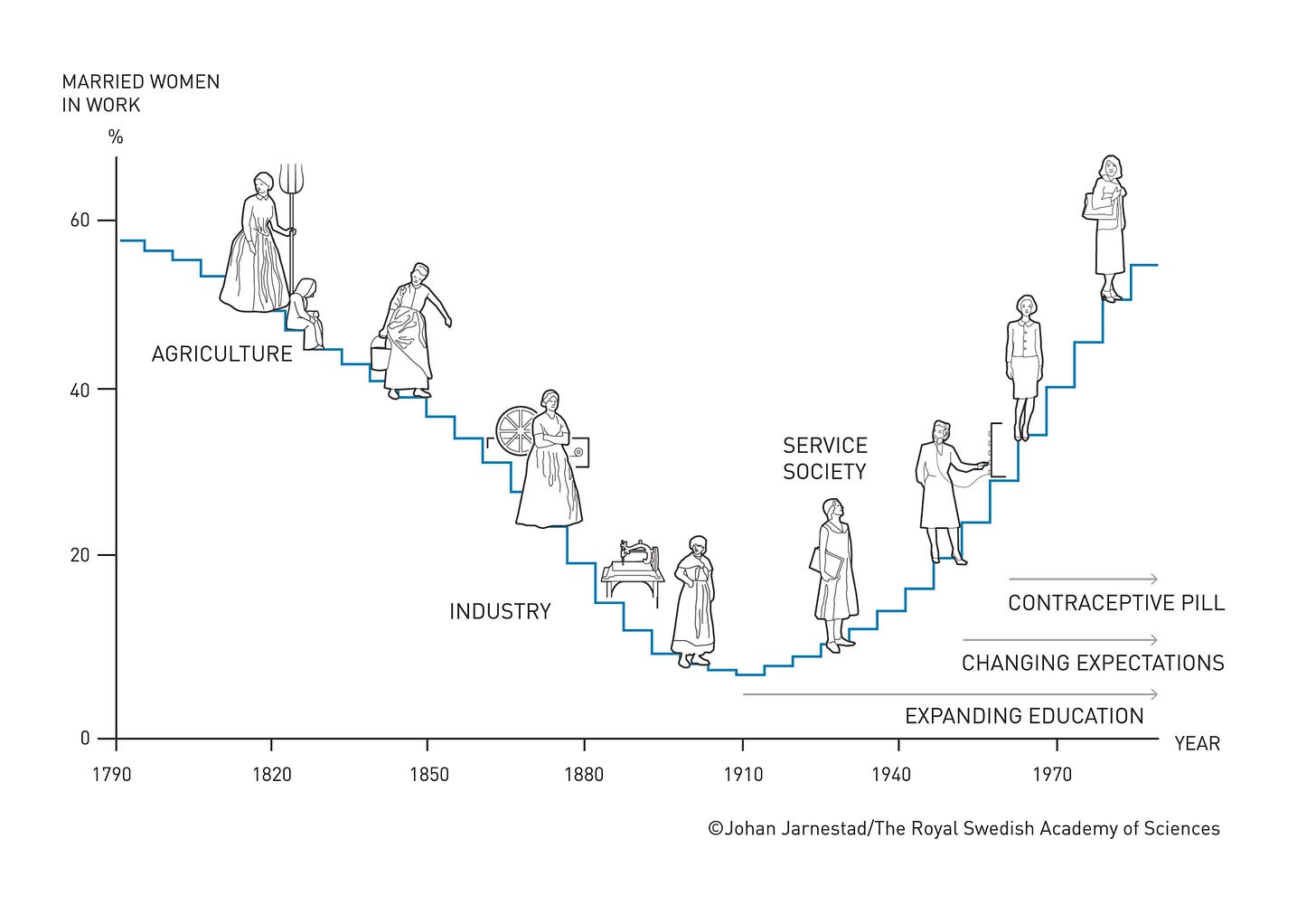

When Claudia Goldin won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2023, she did so for showing the U-shaped curve in female labour participation since the Industrial Revolution.

This graph from the Nobel Committee shows how the liberation of women from physical work preceded increased formal labour participation. Increased gender representation is a euphemism for getting women out of the home and into the mines. In this chart progress looks exactly the same as regression. As soon as women were unshackled, they were thrown back into the workforce, except this time in the name of progress. That women choose to work is a half-truth. The derangements of dual-income fueled property prices often makes it necessary. And choice is an inadequate gatekeeper for some of life’s paths. Many of the women who are now struggling with their fertility issues have been let down (some will say they were lied to, and I agree). Cultural cues that propel us towards family formation and blind us to the decades long challenges of parenthood and marriage exist for a reason. A twenty year old simply cannot fathom the realities and aspirations and desires of a forty year old or the ineffable pleasures of grandchildren.5

Family life is the very basis of our nationhood. In the last couple of years the Government has boasted about the increasing number of women in the work force. Rather than something to be proud of I feel that this is something of which we should be ashamed.

— Former Australian Prime Minister Paul Keating, 1970

One way in which the feminists are deranged is in their reaction to these realities, not in their diagnoses (which are largely correct). Greer’s The Female Eunuch drips with rebellion against the conditions of womanhood. Against its physical ailments, the male gaze, the deranging competitive desire to be beautiful. Clementine Ford is an Unfortunate, a “богом обиженная” — a perfect Russian term that roughly translates to ‘offensive or upsetting to/about God’. One shudders at the quality of man she attracts — no wonder she rails against marriage. (To be fair, a casual flick through any woman’s Tinder options might radicalise anyone against men forever — I recommend the horrorshow to all my male readers). RFH suffered at the hands of an abusive ex-husband and her disillusion is total. But resentment is no cure. Nor is denial of realities around fertility, nor the abdication of motherhood altogether. Accepting the realities of fertility, the trade-offs of motherhood and work, the inadequacies of men — this is probably the path of maximum sanity. There are exceptions of course. And it’s hard. Life is hard. And the woman’s burden is hardest.

Caesarean probably comes from the Latin word ‘caesus’, which means ‘cut’. It may also derive from the Roman law called “Lex Caesarea”, which mandated that if a pregnant woman died, her baby had to be surgically removed from her womb to bury them separately.

Of course, consent only has a fleeting relationship with parenthood altogether. To quote Yoram Hazony in The Virtue of Nationalism:

True, a husband and wife did usually agree, at one point, to bring a child into the world. But not long after this original act of consent, the difficulties involved in raising a child already bear little resemblance to anything the young lovers may have thought they were consenting to at the time. And the project of raising children only continues to throw up ever new surprises over the decades, including hardship and pain that were scarcely imagined when they first entered into it. Yet this original decision cannot be revisited, giving the parents a chance to renew their consent based on an updated assessment that weighs the benefits each child brings against the suffering endured. Just the opposite: The parents’ consent or lack thereof is irrelevant to their continuing responsibilities, and it is nothing like consent that motivates them as they persist in their efforts to raise their children to health and inheritance. What motivates them is their loyalty, which is the fact that the parents understand the child as a part of themselves—a part of themselves not only for twenty years, as certain philosophers suppose, but for the rest of their lives, forever.

I will leave some of Greer’s advice to the discretion of the reader:

If you think you are emancipated, you might consider the idea of tasting your menstrual blood—if it makes you sick, you’ve a long way to go, baby.

The punchline of this essay was that both sexes are bound by the social technology of marriage for the benefit of civilisation. Yet it’s misunderstood!

As I wrote previously:

Culture also guides you with strange long-ago-forged nudges to get you over blind spots. You don’t know you want grandkids when you’re 20. The challenge is you’ll want them in 30 — 40 years. Tell that to a 20 year old and he may have trouble hearing you over the cacophonic need to fight and f*ck. So how do you set the right behavioral cadence for that? What can bridge decades long blind spots? Cultural norms to marry and bear children. The payoff will come.

Good piece. I agree deeply with your assessment that the feminists' critiques are correct- women have historically and continue to have it particularly hard, in ways that are unique to them- but their diagnosis/reaction to it is incorrect, largely because contemporary feminism is committed to denying the biological foundations of the patriarchy, which means there is a very hard limit on how much we can socially engineer the patriarchy out of existence.

As you said, Germaine Greer wrote in "rebellion against the conditions of womanhood." I also had the same realisation very recently- the original feminists of the 1970s were not rebelling against patriarchy as much as they were rebelling against *being female* and femininity itself. They hated being female and the way it was the essence of their political and social subordination- thus they were motivated to reject femininity as a real and valid social identity (see Judith Butler), and to deny that men and women are meaningfully psychologically different (see Julie Bindel). Which is of course nonsense.

This also explains why so much of modern feminism as a project has bought into the premise that women are merely suppressed men- that the ultimate success criteria for the modern woman is to what degree can she attain the markers of success that have been typically reserved for men- money, status, political and economic power: the corporate girlboss. This has been genuinely great for all the intelligent women who have always yearned to be more than a housewife- but I'm not sure it has really translated to improved life satisfaction for all the women who *dont* have ambition or aspiration- i.e., the majority of people.

Indeed, I think a deeply interesting and under-explored event is that the emancipation of women has *not* translated to widespread improvement in the happiness of women in the western world: https://law.yale.edu/sites/default/files/documents/pdf/Intellectual_Life/Stevenson_ParadoxDecliningFemaleHappiness_Dec08.pdf

This is not to argue that emancipating women wasn't good or just, but rather that it hasn't materialised in expected or desire outcomes, like so many other social revolutions. I think part of the reason is that contemporary feminism is just based on the denial of harsh realities. Men and women are different, and these differences aren't going to go away because we want them to. Thus, the question of women's role in society remains unresolved.

Misha, this was a thoughtful piece. I think I have encountered both: women who gave up careers for kids and vice-versa. Most often, women who tried to do both (e.g. my mom), but always something had to give a bit. Overall, having kids is "safer", and would recommend it to 90% of even smart women, but a sort of "bitterness" is there. Especially because, as time goes, husbands become less excited with their wives so there isn't even that anymore. the other thing we do not realise is that, as economies have become more specialised, it's much harder to have contact with the real world as a SAHM. If you were a Queen you could hope to influence events via family connections.... Now, that it basically impossible without some sort of career to speak of.

I do not think there is a solution.... My advice for young women would simply be to find the best man available, that will dictate how much you can do. That means a combo of capable/ambitious and actually empathetic man (again, hard, these two traits do not go well together.) The good thing is that high quality men feel your piece without having to have it spelled out, so they will try to help as much as they can. But these men are not that abundant....